Since it was announced that Torquay was getting a brand new Bierkeller themed bar, questions have been coming in about the building. Many of us remember the Blu Cargo Canteen Bar and even the Piazza, but that imposing building just off Fleet Street has a much longer history.

It was built as the Salem Chapel in 1839 and was the church of an odd religious sect known as the Starkites. Their charismatic leader was local prophet and writer Robert Stark. Born in Chelston in 1788, Robert was raised in the Church of England tradition. However, in 1814 he seems to have decided that the Anglican Church was a bit lightweight and he joined a group of Calvinist dissenters. These were Christian fundamentalists and couldn’t be described as fun people. They believed that humanity was totally depraved and corrupted. As they held that Scripture had the final authority, they spent a great deal of time reading the Bible and trying to convert everyone else before the expected return of Jesus and the imminent end of the world. They also had a fondness for disrupting the meetings of other rival Christian sects, such as the Millerites. The 1851 Devon Religious Census says that Robert’s congregation of Starkites had around 250 members.

Robert died in 1854, the Second Coming of Christ didn’t happen, and a few years later the Salem Chapel closed. Since Robert Stark was into apocalyptic imagery about the end of the world, he may well have appreciated the sentiments of Eve of Destruction by local band Kohoutec who feature in this 1995 clip from what was then the Piazza:

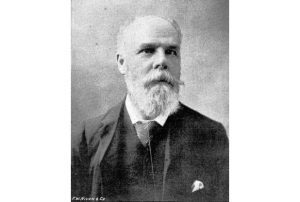

Then came the first reinvention of the building. In 1887 it became the School of Science and Art, and then the Vivian Institute. It was set up by Edward Vivian (1808-1893), the joint proprietor of the Torquay Bank, an hotelier, magistrate, writer and public speaker, member of the Local Board and editor of the Torquay Directory. Together with William Pengelly, Edward (pictured below) played a leading role in the exploration of Kent’s Cavern. He was a Liberal and he took the side of the Salvation Army when they were being persecuted and jailed in Torquay in 1888. On the other hand, he believed that existing political structures were largely correct and he opposed the secret ballot and the universal franchise.

Edward believed that the working classes faced three main problems: lack of educational opportunity, drunkenness and low wages. It was to raise the educational levels of local people that he set up the Vivian Institute. Here working men could attend evening classes in carpentry, joinery, painting, stonemasonry and turning. They paid 2 shillings a month and received three two-hour lessons a week. He also campaigned for a public library, lectures and reading rooms. To tackle drunkenness, he founded the Torquay Temperance Society. To increase the incomes of workers Edward arranged for firms in Manchester to take families of the unemployed from St. Marychurch to get higher paid employment in the north.

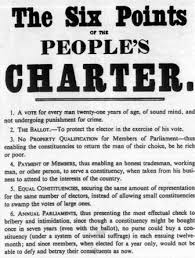

Edward was involved with many philanthropic campaigns and it was his practical solutions to poverty that brought him into contact with local Chartists, representatives of the first mass working class labour movement. Chartism was a movement for political and social reform between 1838 and 1850. It took its name from the People’s Charter of 1838, which stipulated six main aims: a vote for every man over 21 years of age; a secret ballot; no property qualification for members of Parliament so anyone could be an MP; payment of MPs; equal-sized constituencies; and annual parliaments to make MPs responsive to their constituents.

The Chartists adopted the motto “peaceably if we may, forcibly if we must” and they directly challenged the government. To the Victorian authorities they represented a potential for upheaval and the overthrow of social institutions. In response, troops were used to ensure order. Accordingly, since reports of Chartist activity in Torquay were written by the town’s elite, they are uniformly hostile. There may also have been a decision made to downplay any influence the Chartists may have had. Nevertheless, Chartists were active and we can get an idea of how they were perceived by Torquay’s gentry from the several reports of a Chartist meeting that was held in September 1846. The reports of the event suggest that the Chartists had to disguise their activities as attempts to rent meeting rooms were refused. Hence, the Temperance Hall was booked for a less-provocative purpose. This is from the Torquay and Tor Directory:

“The room was applied for on this occasion for the purpose of delivering a lecture explanatory of the scheme proposed by the Land Co-operative Society, with the distinct understanding that nothing political should be introduced. To the surprise and disgust of the Committee and Members of the Society, the Lecture soon degenerated into a coarse Chartist declamation, the Lecturer endeavouring by exaggeration and calumny, to poison the minds of the ignorant against every institution, social and political, by which, under the blessings of providence, the industrious classes of this country have so long been raised above those of every nation upon earth.”

The report referred to the ‘Chartist Agitator’ who addressed the meeting as the “slave of the mob who pay him”. To the horror of the observer, the Chartist had commented that “a servant, whatever may his wages, cannot feel as a man”, and he used “coarse ribaldry… to assail the most hallowed principles of our political and social institutions”. Another hostile report of the meeting condemned “the recurrent attempts of Chartist agitators to influence this town”, and Chartism’s “diabolical tendency to infuse envy, hatred, and malice, between the different classes of our countrymen”.

A letter to the Directory called for “just influence to be restored to those whom providence has designed to be the natural leaders of Society, by education, character or station”.

From newspapers of the time we know that the turmoil of the French Revolution was still in the minds of many, and they reacted in fear at the possibility of any challenge to privilege and position. A letter written to the Directory asks, “Is it possible that any who call themselves Christians can ally themselves with such as this – can advocate rebellion and civil war as lawful means for overthrowing the powers which are ordained by God?”

Unfortunately, we don’t know much more about those Chartists who caused so much concern to Victorian Torquay, or if any of those attending the meeting were involved in Torquay’s Bread Riots the following year.

By the 1840s the Chartist campaign for electoral reform had been frustrated by jailings, failed armed uprisings and intimidation. In response, parts of the movement had moved away from demonstrations and violence and had become committed to peaceful and legal means. In 1843 the National Charter Association was established, “to provide for the unemployed, and give means of support for those who are desirous to locate upon the land”.

At its peak, the National Charter Association had 70,000 shareholders and 600 local branches, one of which was in Torquay. In 1848 Edward let ‘allotments’ of his land at his house ‘Woodfield’ in Lower Woodfield Road (pictured above) to 16 members of the National Charter Association. The aim was to encourage everyone to grow their own food, and eventually 38 quarter acre plots were set up in the Lincombes. However, the experiment in land reform failed – many of the smallholders had little or no experience of agriculture and no idea of how to make their allotments a success. There were also better wages to be had in industry or in service. Nevertheless, the Chartists and their philanthropist allies are part of a long tradition of taking land into group ownership and of – what we now call – lifestyle politics.

The Chartists failed to convince Parliament to reform the voting system at the time. However, the ‘Torquay Agitators’ were ultimately successful: five of the six points in the Charter were adopted by 1918. Chartism also gave impetus to much wider reforms and the political party system we now take for granted.

Now the old Salem Chapel is about to rise again as Torquay’s Bierkeller. If they were still around we can assume that the evangelical Reverend Stark and his Starkites, and Edward Vivian and his Torquay Temperance Society friends, would not have approved. On the other hand, as Chartists were known to organise from the back rooms of pubs, we can perhaps suggest that our Agitators had the last laugh…