“The ward is strangely hushed today;

The morning nurses, sober-eyed,

Recall the screened space, where, they say,

At midnight Number Twenty died.

So many weeks of weary hours

He lay and heard our busy tread,

As patient as the wistful flowers

That spent their fragrance near his bed –

So oft we saw, in passing by,

His questing glance, his dreadful face,

We shall regard resentfully

The stranger that must fill his place…”

‘Out of Conflict’, Alberta Vickridge

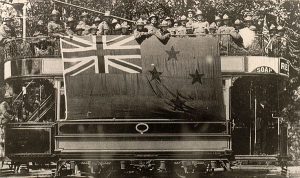

In August 1914 Torquay Town Hall was placed at the disposal of the Red Cross Society and became one of our town’s five war hospitals. It opened with 50 beds and welcomed the first convoy of wounded on 21 October when a hospital train arrived at Torre Station with eight British officers and 40 men from France. More badly injured British soldiers from the campaigns in France, Flanders and Gallipoli arrived at the hospital, followed by wounded from the New Zealand Expeditionary Force – the New Zealanders are below pictured on a Torquay tram in 1918. The other Torquay war hospitals included the Western Hospital for Consumptives, the Officers Hospital at Stoodley Knowle, Ockenden Convalescent Home and the Torbay Auxiliary Hospital at Rockwood. There was also a long-stay home at Royden for men who had been blinded.

Even in Torbay the men weren’t safe. In September 1918 there was a serious epidemic of influenza and over 100 US servicemen died at another Bay hospital in just a fortnight.

In September 1915 King George and Queen Mary visited. It was recorded that, “Their Majesties devoted a week to visiting war hospitals in the West. On the sixth, they were at Bristol, the next day at Exeter, and on the eighth and ninth at Plymouth; on the 10th they arrived in Torquay with Lord Stamfordham, Commander Sir Charles Cust, Bt. , Royal Naval Equerry, and Major R. H. Seymour, Military Equerry, and were received at Torquay Station by the Mayor, Councillor T. Towell and the Mayoress with the Town Clerk. The party then drove to the Town Hall via the seafront, Kings Drive, and Falkland Avenue. At the entrance to the Town Hall was stationed a guard of honour of the St John’s Ambulance Brigade. Their Majesties remained in the hospital three quarters of an hour and spoke to each of the 200 soldiers there.” The images above and below left show the royal visit.

It’s fairly well known that a young Agatha Christie lived and worked as nurse in Torquay during the Great War. Less known was another Torquay nurse who came to know Agatha well. This was the poet Alberta Vickridge (1890-1963) who contributed to the magazine Agatha edited. During her long writing career Alberta had nine poetry books published, won a Bard’s Crown and Bardic Chair at an Eisteddfod in 1924 for her poem, ‘The Forsaken Princess’, and ran her own printing company alone from the attic of her home.

Alberta was born in Bradford, one of three sisters brought up in a strict Methodist household. After leaving school she began to write poetry and articles for national and regional magazines and newspapers. She also reviewed books for The Yorkshire Observer and had poems published in magazines such as Country Life, the Lady’s Companion and The Woman at Home.

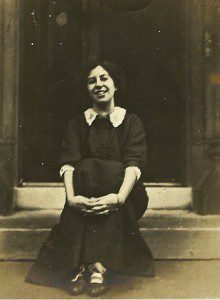

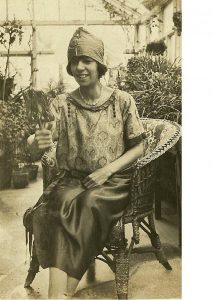

When the Great War began in 1914, Alberta (pictured below right and left) was in her mid twenties and was a regular contributor to The Wayfarer, a well-regarded literary magazine. She knew its editor and, when he was called up in 1916, Alberta took over his role – a post she kept until 1927.

When the Great War began in 1914, Alberta (pictured below right and left) was in her mid twenties and was a regular contributor to The Wayfarer, a well-regarded literary magazine. She knew its editor and, when he was called up in 1916, Alberta took over his role – a post she kept until 1927.

Because of her mother’s poor health, the family often spent the winter months in Torquay. She loved our town and expressed her feelings in the following poem ‘Devon Blue’:

Every morning when I awake,

Greeting day and life anew,

First, a cup of tea I take

From a set of Devon-blue.

Cup and saucer, pot and plate –

On each separate piece I view

Seagulls on a rock, sedate,

‘Gainst a sky of Devon-blue.

Even so in mild Torbay,

Dawlish, Brixham, Teignmouth too,

Deeply sapphire gleams the day

From a sea of Devon-blue.

Though my Northern home is far

From the seas and skies I knew,

Brighter all my mornings are

For a glimpse of Devon-blue.

I forget how mist and rain

There as here change heaven’s hue,

Living happy hours again

In a world of Devon-blue.

While in Torquay, Alberta decided to contribute to the war effort and volunteered to join the Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD) in late 1917. That’s Alberta in her VAD uniform at the beginning of this article. The Voluntary Aid Detachment had been established in 1910 to provide volunteers to support the professional military nursing service. The War Office recognised that in the event of war the Home Defence Force would require clearing hospitals, ambulance trains, rest stations and convalescent homes alongside private hospitals. Separate branches of the VAD force were subsequently formed for women and men – women became nurses while the men served as ambulance drivers, orderlies, stretcher bearers and cooks. Though VAD nurses were regarded as ‘Probationers’, they still needed to be able to deal with very serious injuries.

The VAD rapidly expanded on the outbreak of war in August 1914 and had 80,000 volunteers by 1916. However, limited funding was allocated by the Treasury and so the County Finance Committees relied on fund raising and the donation of vegetables, fruit and eggs. By May 1917, the Devon VAD hospitals had received over 17,000 patients in direct convoys from Southampton and other ports, transferred by ambulance trains to towns across the county.

The experience of working with wounded men in the Torquay Town Hall Hospital must have been traumatic for a sheltered and relatively privileged woman, but Alberta seemed to cope well. Indeed it was her nursing experiences that led Alberta to write two of her most anthologised poems: ‘In a VAD Pantry’ and ‘Out of Conflict’- part reproduced at the beginning of this article. In a letter from Agatha to Alberta we see that Christie admired Alberta’s work and that the two women had become friends. In 1918 Alberta submitted ‘Out of Conflict’ to a competition in the Poetry Review and won the first prize, beating Wilfred Owen’s ‘Song of Songs’ into second place. Wilfred was killed in action later that year.

When the War ended, Alberta stayed on in Torquay for a while. Encouraged by her success she worked on a book containing war poems and others on the topics of nature and romance – ‘The Sea Gazer’ was published in 1919. After the War, Alberta produced the Jongleur poetry magazine which ran for nearly thirty years. She never married and died at the age of 73. Alberta is buried with her mother and father near Saltaire, West Yorkshire.

Here’s ‘In a VAD Pantry’ written by Alberta during her time as a nurse in Torquay Town Hall Hospital:

In A VAD Pantry

Pots in piles of blue and white,

Old in service, cracked and chipped–

While the bare-armed girls tonight

Rinse and dry, with trivial-lipped

Mirth, and jests, and giggling chatter,

In this maze of curls and clatter

Is there no one sees in you

More than common white and blue?

When the potter trimmed your clay’s

Sodden mass to his desire–

Washed you in the viscid glaze

That is clarified by fire–

When he sold your sort in lots,

Reckoning such as common pots–

Did he not at times foresee

Sorrow in your destiny?

Lips of fever, parched for drink

From this vessel seek relief

Ah, so often, that I think

Many a sad Last Supper’s grief

Haunts it still– that they who died,

In man’s quarrel crucified,

Shed a nimbus strange and pale

Round about this humble Grail.