All appeared well at the turn of the century with Torquay the centre of the British Empire at play. But World War I was a prolonged, brutal, and costly conflict; and was followed by a virulent pandemic which killed even more people. Across the Bay the impact of the so-called Spanish Flu was severe, with theatres, dance halls, churches and other public-gathering places being closed. In 1919 the exceptional nature of the pandemic, its rapidity and randomness, was described by the town’s health authorities:

“The disease was of an unusual type. The onset being quickly followed by a toxic form of pneumonia, which was little effected by treatment and rapidly proved fatal. Strong robust individuals and pregnant women nearing the end of their confinement were common victims. In the latter abortion took place, quickly followed by death”.

In 1921 Torquay had a population of 39,431. All were affected by those two seismic events in a time of grief, social change and the end of certainties, an erosion of self-confidence that the historian Correlli Barnett argues “crippled the British psychologically“.

The physical manifestations of mourning could be viewed in the town’s workplaces and in private shrines in so many homes. Remembering was rightly manifest and central in the building of monuments to the Fallen, the most notable being Blomfield’s 1920 War Memorial in Princess Gardens. Few would not have known a friend or family member among the 609 named there. And everywhere those broken in body and mind could be seen in Torquay’s streets.

As Torquay entered the ‘Roaring Twenties’, it steadily became evident that this would be a decade of contrasting and polarising experiences. The ‘Bright Young Things’, those born after the turn of the century and with the privilege of wealth, had a good life in a party town, freed from the restrictions their parents experienced; though perhaps they lived with a sense of guilt and reacted through a life of hedonism. Conversely, those returning from Flanders, expecting the ‘land fit for heroes’ promised by Lloyd George, were to be disappointed. Wages were being cut as the country had lost overseas markets and faced growing competition, particularly from the USA and Japan. Many would face a period of unemployment, deflation and economic decline. This would lead to political upheavals and attract some to the superficial attractions of Bolshevism or Mussolini’s fascism.

The English Riviera self-image presupposed Torquay as an international town. But it also saw itself as a product of a benign imperial mission. Yet the Empire was fraying and the treasured family of nations beginning to dissolve. England’s oldest overseas colony had already decided on divorce and debates over Irish Home Rule had divided Torquay’s politics for decades. In Ireland nationalists fought a brutal civil war from 1919 to 1921 and when the Anglo-Irish Peace Treaty created an Irish Free State this represented a territorial loss for Britain that was equal to that experienced by Germany in 1919. Further afield, participation in the War appealed to a growing sense of nationalism. Many recognised that it would be only a matter of time before the Empire was dismantled entirely.

Conscription had eroded traditional class distinctions and self-regulating deference. Families had grown to like earning wages in factories while new advances in technology reduced the need for a large local servile class. During the War many women had been employed, giving them a wage and a degree of independence. Women over 30 gained the vote in 1918, and by 1928 this had been extended to all women over the age of 21. This was reflected in new fashions; shorter hair and shorter dresses, while women started to smoke, drink and drive motorcars. The ‘flapper’ appeared, perplexing a staid seaside society.

Torquay had always focused on attracting the upper class visitor. However, the elite had taken the greatest proportional hit during the War. There were just fewer confident and educated sons of privilege around. In a symptom of social change Torquay’s much anticipated opera house would never be completed.

All faced a decade of disorientation. Indeed, some historians see 1914 as the real end of the Long Nineteenth Century, the conclusion of a British Belle Époque. From then on, so many convictions and accepted truths would inevitably crumble as long-accepted hierarchies of class and gender rapidly decayed. Social relationships which had taken a century to build up were being dismantled, creating a modern Torquay so different to that of the Victorians.

But not all had changed; some old ways endured. Despite the assumptions of Victorian and Edwardian rationalists residing in their villas and hotels on the hills, ancient beliefs about the supernatural lingered on in urban Torquay. In an uncertain world before adequate health and social care, survivals of old practices such as faith healing, magical protections and folk remedies were particularly prevalent amongst the poor and the working class. Fear of malign supernatural forces persisted. Alleged witches were attacked in Brixham in 1913 and in Paignton in 1919. Even in supposedly trendsetting sophisticated Torquay, in 1921 a man was summoned before the town’s magistrates for spitting in the face of a woman who, he claimed, had cursed his seven children.

But not all had changed; some old ways endured. Despite the assumptions of Victorian and Edwardian rationalists residing in their villas and hotels on the hills, ancient beliefs about the supernatural lingered on in urban Torquay. In an uncertain world before adequate health and social care, survivals of old practices such as faith healing, magical protections and folk remedies were particularly prevalent amongst the poor and the working class. Fear of malign supernatural forces persisted. Alleged witches were attacked in Brixham in 1913 and in Paignton in 1919. Even in supposedly trendsetting sophisticated Torquay, in 1921 a man was summoned before the town’s magistrates for spitting in the face of a woman who, he claimed, had cursed his seven children.

A practice closely associated with seaside resorts was fortune-telling. In February 1926 visitors to Torquay Town Hall could visit Gipsy Leah who promoted a romantic narrative of Romani culture and mystical powers. A local journalist was so captivated that he enthusiastically wrote of the,

“Occult science of a beautiful girl with lustrous eyes… with a full measure of that mysterious psychic power, combined with a lovely face… The Gipsy temperament with its passionate love of music, a deep mystic sense and an intuitive ability to read character. She has all the characteristics of her race, with their love of romance and mystery for which her people have been famed for centuries.”

Yet Gipsy Leah wasn’t the usual Torquay end-of the-pier palm reader with a working class clientele. She was “a scientific palmist, helpful particularly in matters relating to matrimony, health or business” who claimed that she had appeared at Wembley where she was “consulted by English and foreign royalty and peers of the realm”. Discrete clients who wished to remain anonymous in their search for future knowledge could arrange special appointments at the Queens Hotel on the harbourside.

This was certainly a lucrative business. We next hear of Leah in April 1926 after an elderly miller had given her £331, believing her to have “superhuman powers”. The man had approached the palmist for a reading as his wife had left him and Leah allegedly promised to bring them together. Yet when this reconciliation failed to come about, the miller went to the authorities and a case of theft was heard at the Exeter City Quarter Sessions. In court it was revealed that Gipsy Leah’s real name was Ida Sheridan. The 34-year-old denied the charge of stealing but did reveal that she could receive more than £500 for her services; the average male weekly wage at the time was around £5.The jury found Leah/Ida not guilty.

Alongside preindustrial forms of belief came new and imported methods of understanding the world. We generalise these beliefs and practices as being ‘occult’, a term which simply refers to the search for hidden knowledge. This is a quest that extends beyond reason and the physical sciences into an exploration of a deeper spiritual reality.

Torquay was certainly fertile ground for fresh and exciting ideas. During the early years of the twentieth century the resort was claiming to be the richest town in England. In its Italianate villas lived a large number of very wealthy residents and visitors who had a lot of time on their hands. The educated and well-travelled sons and daughters of Empire also had opportunities to explore teachings outside of mainstream religion and philosophy and could access cultures beyond Europe. Torquay in consequence established a reputation as being one of the centres of occult thought and practice in Victorian and Edwardian Britain.

Exploring these themes were Torquay’s ‘secret societies’, mutual support networks which had been active since the town’s beginnings. Though primarily philanthropic organisations, Torquay’s Freemasons (founded in 1810), the Oddfellows (1856), and the Foresters (1858) all claimed to have their roots in antiquity; in ancient Egypt, Rome or Anglo-Saxon Britain. Although these organisations, and other associations and individuals, used rituals that concerned the established Church, the occult tradition was mostly not a rival to Christianity but an augmentation to the faith; albeit in often intriguing and dramatic forms.

Further contributing to the growth of the esoteric was the town’s origins and character as a resort. Torquay was built on tourism and for many decades the needs of the visitor and the holiday trade came before all other considerations. There was no denying the good reasoning behind why the town fashioned itself around the industry; by 1911, 55% of English people were visiting the seaside on day excursions, while 20% were taking holidays requiring accommodation. This reliance was therefore an understandable response to the reality of the paying visitor who generated revenue that, in ideal circumstances, would benefit all social classes.

The services that provided employment in the resorts were generally small businesses, run on hierarchical lines. This meant that traditional working class and radical movements found it difficult to organise and thrive. Without large-scale manufacturing industry the hegemony of the tourist trade, and the dominance of hoteliers in alliance with Conservative politics and the Church, carried on largely unchallenged. Trades unions found it difficult to recruit, working class organisers were dismissed and evicted from their homes. In such a hostile environment the esoteric tradition offered a diversion and a refuge for those wanting to change their world. And evident are the interrelationships between suffrage, feminism, socialism, Irish Home Rule, temperance, vegetarianism, nonconformist Christianity, non-traditional sexual relationships, and the occult in all its forms.

Aleister Crowley

Torquay’s wealth, fame and openness to new ideas attracted, and gave platform to, eccentrics, provocateurs, self-publicists and pioneers from the esoteric tradition. The best known of these was Aleister Crowley, “the wickedest man in the world”, who revelled in his reputation as a practitioner of ‘Magick’. Crowley’s own brand of religious philosophy would later lead him to establish his Abbey of Thelema in Barton.

Linking these disparate concepts in the 1920s was the revival of spiritualism, an enthusiasm that began in 1848 when the Fox sisters in New York claimed that curious rapping sounds were messages from the spirits of the dead. In 1852 table rapping came to England and Torquay quickly seized on the new sensation. Darwinian evolution and other scientific advances were challenging biblical claims while the working classes were drifting away from church attendance, and so the town was ready for something that would reassure the public that there really was an afterlife.

Spiritualism was initially respectable, Queen Victoria practiced table rapping, and contacting the dead became a mix of religion, parlour game and public entertainment. Importantly, it gave women power and respectability in a patriarchal society.

Percy Fawcett

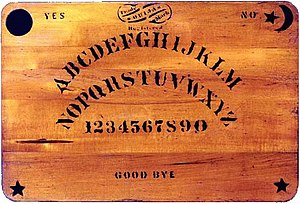

Rapping, however, was a very tortuous way of communicating and so mediums developed the talking board, later called a Ouija, which could quickly spell out an answer. Aleister Crowley admired the Ouija board and it played a role in his magical workings. He believed that the board used the same principles that were practiced by the Elizabethan magician John Dee, who used a crystal ball as a means of ‘skrying’ or seeing into invisible realms.

Another Torquay Ouija adherent was explorer Percy Fawcett. An artillery officer during the Great War, Percy used the board to counter German heavy guns. In late 1916 when he arrived to take up his new post of corps counter-battery colonel, he immediately declared that he was “not in the least bit interested in the innovative work being done on the detection of German guns by flash-spotting and sound ranging… The only counter-battery shots which he would allow were those against targets clearly visible from British lines – or those he had personally detected on his Ouija board.” Percy, along with his eldest son, disappeared in 1925 during an expedition to find a lost ancient city in Brazil which he believed to be the remains of El Dorado. Ouijas also offered a useful plot device to Agatha Christie who had an interest in the paranormal. ‘The Sittaford Mystery’ (1931), set in a lightly disguised Okehampton, features a talking board.

Another Torquay Ouija adherent was explorer Percy Fawcett. An artillery officer during the Great War, Percy used the board to counter German heavy guns. In late 1916 when he arrived to take up his new post of corps counter-battery colonel, he immediately declared that he was “not in the least bit interested in the innovative work being done on the detection of German guns by flash-spotting and sound ranging… The only counter-battery shots which he would allow were those against targets clearly visible from British lines – or those he had personally detected on his Ouija board.” Percy, along with his eldest son, disappeared in 1925 during an expedition to find a lost ancient city in Brazil which he believed to be the remains of El Dorado. Ouijas also offered a useful plot device to Agatha Christie who had an interest in the paranormal. ‘The Sittaford Mystery’ (1931), set in a lightly disguised Okehampton, features a talking board.

Mediums, however, needed to compete for an audience and so séances moved on from simple table rapping and Ouija boards to feature a range of increasingly bizarre supernatural phenomena. These could include spirit writing, furniture floating in the air, possession by spirits, and accordions playing themselves. This escalation would eventually lead to the full materialisation of spirits. A ‘spirit’ would leave its cabinet and wander amongst the audience, perhaps trailing ‘ectoplasm’; supposedly a supernatural vapour that sometimes solidified.

By the 1920s spiritualism had attracted inevitable criticism and scrutiny, it having been noticed that sometimes the spirits had interests originating in this life rather than the next. In response the Society for Psychical Research had been established in 1882 and had exposed a range of trickery. The Society’s investigators found that fraudulent mediums used confederates, hidden compartments, sleight of hand and even electrical devices. Posing as members of the public, they would ‘break the circle’, seize hold of ‘apparitions’ and find they were disguised mediums or their assistants. Consequently, many mediums gave up and left their profession, some emigrating to Australia.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

Nevertheless the practice again became popular during the mass grieving following the War. One prominent advocate was the Sherlock Holmes author Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. During the conflict he had lost eleven family members either in combat or to disease, his eldest son and only brother among them. He launched a crusade proclaiming his belief in the afterlife which met with a positive response among the many around the world who had similarly suffered bereavement.

Henry Paul Rabbich

Torquay was a natural stage for a Conan Doyle visit and on 5 August 1920 he delivered a lecture entitled ‘Death and the Hereafter’ at the Town Hall. The meeting was presided over by local builder and Freemason Henry Paul Rabbich, the then President of Paignton Spiritualist Society. During this visit, Sir Arthur stayed with Henry at ‘The Kraal’, 5 Headland Grove, Preston. The newspapers remarked how the appreciate audience was mainly female though not all locals were so welcoming. Sir Arthur later recalled that the Town Hall “was next to a church, and just as I started to speak the church bells began ringing, and I had to shout all the time.” This attempted sabotage seems to have come from the Anglicans of St Mary Magdalene’s. In February 1923 Conan Doyle returned to give a lecture at the Pavilion entitled ‘The New Revelation’, “the culmination of his many years of research as a Spiritualist”, presided over by Torquay’s Mayor GH Tredale. He stayed at the Victoria Hotel in Belgrave Road on this visit. Many, however, ridiculed Conan Doyle’s beliefs in the afterlife, psychic channelling, spirit photos, and ancient Egyptian curses.

Always an influence on the development and direction of the local occult tradition was the popular literature of the period. Many Georgian, Victorian and Edwardian writers were associated with the resort and left their mark on the uncanny, pseudo-scientific and occult narrative. These included: Mary Shelley (Frankenstein); Percy Bysshe Shelley (Fragment Of A Ghost Story); Elizabeth Barrett Browning (Pan is Dead); Robert Louis Stevenson (Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde); Charles Dickens (A Christmas Carol); Alfred Lord Tennyson (The Kraken); George Eliot (The Lifted Veil); Arthur Conan Doyle (Sherlock Holmes); TS Eliot (The Waste Land); Rudyard Kipling (Tales of Horror); Oscar Wilde (Dorian Gray); Wilkie Collins (The Woman in White); Henry James (The Figure in the Carpet); George Bernard Shaw (The Miraculous Revenge); James Joyce (The Dead). All lived in or visited Torquay.

Taking one example, in 1859 Edward Bulwer-Lytton wrote his short novelette ‘The Haunted and the Haunters or The House and the Brain’. Based on the famous case of 50 Berkeley Square in London’s West End, this was the first modern haunted house story and it effectively created the genre. Edward lived in Torquay’s Warren Road and certainly knew his subject. He based his story on his twenty years’ study of paranormal phenomena, spiritualism and mesmerism; and his fiction may well have inadvertently inspired one of the most documented paranormal cases on the twentieth century.

Violet Tweedale

Beginning in 1917 a series of investigations were launched into what was supposedly Britain’s most haunted house, the Torquay villa Castel-a-Mare. We know about these explorations from Violet Tweedale’s memoirs ‘Ghosts I have Seen’ (1920). During her long career Violet wrote over 30 books on spiritual subjects, became involved in Theosophy and was a member of the magical Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, one of the largest influences on modern occultism. As a specialist on all things supernatural, Violet was later called as an expert witness in a 1932 legal case when Newton Abbot medium Mrs Meurig Morris sued the Daily Mail for libel.

Castel-a-Mare

Violet conveniently lived near to the haunted villa and organised an eight strong team to explore Castel-a-Mare. The group’s medium was soon possessed by a violent spirit which assaulted the other members using superhuman strength. Another visit was arranged, and the male entity again took control of the medium and launched an attack. The investigators later revealed that a physician “of foreign origin” had strangled the master of the house, murdered a maidservant and was now angrily haunting the building and possessing trespassers.

Beverley Nichols

In 1920 the writer Beverley Nichols, his brother and a friend, Lord Saint Audries, also visited Castel-a-Mare. Searching with only a candle to light their way the three ghost-hunters went from room to room until Beverley fainted and Lord Saint Audries saw a greyish light in the darkness. Something “black, silent and man-shaped rushed from the room and knocked him to the floor. An overwhelming sense of evil overcame him and he struggled to keep his sanity as he ran from the house.” As with the earlier investigations, it was claimed that a mad doctor had killed his wife and a maid in around 1870. No record of these murders seems to exist, however.

What is notable in the Castel-a-Mare reports is that they featured a new form of ghost, the pugnacious poltergeist. For centuries Torquay’s many haunting had been benign, with uneasy spirits merely wanting restitution for past wrongdoings or giving helpful and practical advice to the living. Now we had violent spirits for violent times. And in a possible case of life mimicking art, there are real similarities between Edward Lytton’s fiction and the Castel-a-Mare haunting.

Rudolf Steiner

By the 1920s the arcane tradition had matured somewhat. While practitioners still critiqued what they saw as superficial scientism, they now demanded respectability and acceptance into the mainstream. They constantly searched for evidence of the truth of their claims but their beliefs and practices were always incompatible with the scientific method. Despite venturing forth from the shadows such approaches would remain pseudo-scientific at best. Theirs was an ongoing campaign, however. From 11 to 22 August 1924, for instance, around 200 British, Swiss and Italian delegates attended ‘The International Summer School of the Anthroposophical Society’. Austrian social reformer, architect, and clairvoyant Rudolf Steiner was there to deliver three series of lectures later published as ‘The Kingdom of Childhood’. This was Steiner’s final foreign trip and he was joined by founder members of the spiritual and mystical Biodynamic Movement, the first of the organic farming pioneers.

Rosa Campbell Praed

Bringing together an array of occult themes, associations and networks, is the life of Rosa Campbell Praed, the first Australian novelist to achieve a significant international reputation. Born in 1851 Rosa was brought up on cattle stations in Australia until the age of seven and then the Praed family moved to England where she published her first book, ‘An Australian Heroine’ (1880). It was well received with her writing being described as “extraordinary” as she included Aboriginal people as characters while “eloquently pleading their case for justice and dignity”.

In London the Praeds threw themselves into social activities and they socialised with celebrities such as Oscar Wilde, Conan Doyle, Rudyard Kipling and Bram Stoker. During her long career Rosa wrote over fifty books, her novels mostly being romances though they often concerned the forced choices women make in life, a recurrent theme being of women trapped in a loveless marriage. Not surprisingly male critics were less than appreciative of this undercurrent of cynicism, a “weird melancholy”, or of what was seen as the sexual explicitness of some of her work.

During the latter years of the nineteenth century Rosa’s focus changed. She began to attend and host Theosophical Society meetings and corresponded with occultists including HS Olcott and Madame Blavatsky. Mystical themes then emerged in her work; she recorded conversations with supernatural entities while her novels featured mesmerism, telepathy and duel personalities. Rosa adopted the ideas of WB Yeats and Dion Fortune, studied Buddhism and Hinduism, and embraced magical societies such as the Golden Dawn. A recurrent theme was a belief in reincarnation. This fascination with past lives was reinforced when Rosa met the Anglo-Indian medium Nancy Harward. Rosa and Nancy began to live together and they moved to Torquay in the early 1920s. They maintained their contacts with the Theosophical Society which had a popular base in the town; the Charter of Torquay’s Theosophical Lodge had been signed by feminist, Fabian Society member, and Indian Home Rule campaigner, Annie Besant on 31 January 1914.

During Nancy’s life, and after her passing in 1927, Rosa maintained a dialogue that told of how Nancy would assume the personality of a former incarnation: “This is how I made the acquaintance of Nyria, slave attendant upon Julia the daughter of Titus, emperor of Rome, 79-81AD”. In a hypnotic trance Nancy would describe scenes and events of this past life and when Nancy died mediumistic conversations continued. These transactions were published in 1931 as ’The Soul of Nyria: The Memory of a Past Life in Ancient Rome’; Rosa was then 80 years of age.

Annie Besant

The early twentieth century esoteric tradition encompassed a broad collection of themes: including the traditional haunting, secret societies, folklore, magic, spiritualism, pseudo-science and Eastern religions. It was further associated with non-traditional lifestyles and radical political and social movements. This was a morbid interlude and into a confusing landscape of great social change came new and often anti-rationalist ideas alongside the re-emergence of old traditions. Much of this is our inheritance and remains with us still.

Dr Kevin Dixon is the author of ‘Torquay. A Social History’