Now that we are nearing our tourist season it’s important that our visitors don’t miss out on the local Treacle Mine experience!

Marldon, Chudleigh and Daccombe are all small communities where treacle could once be mined.

The good folk of Dunchideock on the Haldon Hills have even given a scientific explanation for their subterranean reservoirs. They cite the geological compression of ancient sugar-cane forests that now, millions of years later, ooze the treacle.

Of course, treacle is uncrystallised syrup usually made during the refining of sugar, so those fortunate to live in places where it could be found underground were very healthy, especially the miners themselves. However, demand for this mined treacle was so high that the actual sites had to be kept secret to prevent the goodness from being pillaged.

The Treacle Mine has been a joke played on the gullible for over a century and is a way for local folk to mock and test the credulity of tourists.

The Treacle Mine has been a joke played on the gullible for over a century and is a way for local folk to mock and test the credulity of tourists.

Similar jokes were also made about snuff mills, jam mines, or toothpaste quarries. It was about something nonsensical or impossible. And we do like playing pranks on newcomers. Even today new workers are initiated by being sent out on a fool’s errand, such as to buy striped or tartan paint.

Similar jokes were also made about snuff mills, jam mines, or toothpaste quarries. It was about something nonsensical or impossible. And we do like playing pranks on newcomers. Even today new workers are initiated by being sent out on a fool’s errand, such as to buy striped or tartan paint.

It was also a way to warn children that if they misbehaved they could be sent to work in the local treacle mine.

It was also a way to warn children that if they misbehaved they could be sent to work in the local treacle mine.

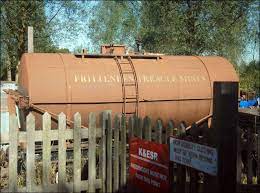

The folk myth has been around since at least the nineteenth century. Pubs, restaurants and hotels have borne the name. The Kent and Sussex Railway even has a Frittenden Treacle Mines wagon.

However, some have suggested that the idea of hidden hypogeal nourishment goes much further back. The Greek derivative ‘thereical” means medicine, so medieval healing wells were called ‘treacle wells’ – note the Dormouse telling of a treacle well in Alice in Wonderland (1865).

“‘Once upon a time there were three little sisters,’ the Dormouse began in a great hurry; ‘and they lived at the bottom of a well . . .’ ‘What did they live on?’ said Alice, who always took a great interest in questions of eating and drinking. ‘They lived on treacle,’ said the Dormouse”. (Alice in Wonderland, Lewis Carol, 1865) The thing is that we don’t really know the origin of treacle mines. And there may be more than one point of genesis as such tales occur in at least twelve counties across England. Accordingly, various myths are peculiar to the small villages that claimed a treacle mine.

The thing is that we don’t really know the origin of treacle mines. And there may be more than one point of genesis as such tales occur in at least twelve counties across England. Accordingly, various myths are peculiar to the small villages that claimed a treacle mine.

One possible origin is from 1853 when 8,000 soldiers were camped on Surrey’s Chobham Common. When the soldiers left for the Crimean War some barrels of treacle were buried, but later discovered by villagers who were called ‘treacle miners’.

Another suggestion comes from Maidstone’s Tovil Treacle Mines. During the Second World War, the paper industry faced a shortage of imported timber. And so these paper mills tried fermenting straw which created sticky goo that looked like black treacle.

Another suggestion comes from Maidstone’s Tovil Treacle Mines. During the Second World War, the paper industry faced a shortage of imported timber. And so these paper mills tried fermenting straw which created sticky goo that looked like black treacle.

In Tadley, Hampshire, legend describes how locals used treacle tins to store money because the banks could not be trusted. These were buried around the village and criminals mined for the tins.

In Ware, Hertfordshire, when asked “where have you been?” it was common to answer, “down the treacle mines”.

So why is there a reported cluster of treacle mines in our part of Devon? One possibility is that some of the mines on the eastern edge of Dartmoor produced micaceous hematite. That mineral is a glistening black and was used to dust early ink to prevent smearing. It bears some resemblance to black treacle and those excavations are known locally as ‘treacle mines’.

One possibility is that some of the mines on the eastern edge of Dartmoor produced micaceous hematite. That mineral is a glistening black and was used to dust early ink to prevent smearing. It bears some resemblance to black treacle and those excavations are known locally as ‘treacle mines’.

‘Torquay: A Social History’ by local author Kevin Dixon is available for £10 from Artizan Gallery, Lucius Street, Torquay, or:

https://www.art-hub.co.uk/product-page/torquay-a-social-history-by-kevin-dixon