“The necessity for these experiments I dispute. Man has no right to gratify an idle and purposeless curiosity through the practice of cruelty.” Charles Dickens (1812-1870), visitor to Torquay.

Over at Spotted Torquay a question came in about the statue of Georgina Baroness Mount-Temple up at Babbacombe and why flowers keep being placed in her hand. Here’s the story behind the statue.

During the early 19th century, there was a growing sympathy with animals. This reassessment of the natural world can be seen in the exaltation of nature found in Romanticism – Shelley’s poem Queen Mab (1812), for instance, condemned the abuse of animals. Shelley visited Torquay in 1815. Liberal and Christian concern led to a rejection of the idea that animals were things to be exploited, and a movement for reform began to gather. In 1822 the first animal welfare legislation prohibited the cruel and improper treatment of cattle, and in 1835 The Protection of Animals Act outlawed bull, bear and badger baiting as well as cock fighting and dog fighting – though significantly this legislation applied only to domestic and captive animals and not wild animals such as deer or foxes.

The early 19th century saw a proliferation of welfare organisations, the foremost being the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (made Royal by Victoria in 1840). There were also religious societies including The Friends’ Anti Vivisection Society, The Catholic Study Circle for Animal Welfare and The Anglican Society for the Welfare of Animals.

The Victoria Street Society, which became the National Anti-Vivisection Society in 1897, was the world’s first anti-vivisection organisation. Founded in 1875 by Frances Power Cobbe and Toni Doran, the Society was supported by many of the social reformers of the day who were also working for the rights of women, children and workers. Public opposition to vivisection caused the Government to appoint the First Royal Commission on Vivisection in 1875. This led to the Cruelty to Animals Act 1876, an Act that remained in force for 110 years until it was replaced by the Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986.

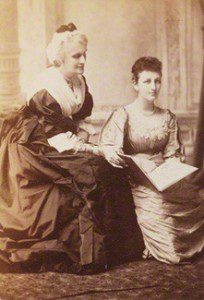

Torquay had a very active anti-vivisection movement. One of the local leaders of the Torquay Anti-Vivisection Society was Babbacombe’s Georgina Baroness Mount-Temple – the step-daughter-in-law of Lord Palmerston and a friend of John Ruskin and Dante Gabriele Rossetti. Georgina can be seen in this photograph (below) along with Juliet Latour Temple.

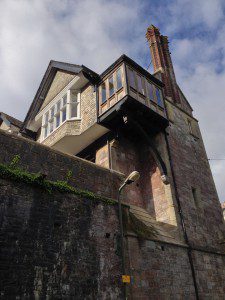

A great humanitarian, her interests also included the Band of Mercy, whose first President was Lord Mount-Temple, the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, and the Temperance Movement. She lived at Babbacombe Cliff (later re-named the Babbacombe Cliff Hotel and now flats) and fed birds from the veranda at the front of the house. Georgina died in 1901 and her obituaries recorded a woman who campaigned with “passionate indignation against cruelty and injustice…” However, the Manchester Guardian felt it necessary to comment on her commitment to “lost causes and impossible beliefs”.

In 1903 a bronze statue was erected by her friends in her memory. Even today a few picked flowers can often be seen in the hands of the statue which still stands in Babbacombe. There’s also a horse trough dedicated to Georgina at the Torre Station end of Avenue Road. Indeed, practical provision was often made by those campaigning for the welfare of animals. In Dartmouth’s Charles Street, there’s a horse trough with a drinking fountain. Dated 1898, the trough is set with lead letters which record that it was erected, “in memory of Henrietta Loraine, a founder member of the SE Devon branch of the RSPCA and, for 10 years, secretary of the Torquay Anti-Vivisection Society”.

Notably, many of the activists in the 19th century animal welfare movement were women. Links between animal experiments and the treatment of women in the Victorian era can be made: both animals and women were seen as property; submission to a ‘higher’ authority was expected; and there were parallels between the restraining and surgical implements used on animals and in the medical treatment of women, such as in childbirth and gynaecological examinations. It’s interesting that most women’s medical colleges were actively anti-vivisectionist, while men’s were not.

By the early 1920s, popular political support for the anti vivisection movement had declined. Women and working men had won the vote, and there was no longer such a close link between campaigns for animal welfare and demands on the political establishment as there had been in the 1800s and early 1900s. Nevertheless, the anti-vivisection movement continued to campaign. Today, animal welfare and animal rights activists maintain the tradition in Torquay and throughout the rest of the country.

Other animal welfare causes found a great deal of support in Torquay. In 1911 the Council of Justice to Animals (CJA) was formed by a small group of people who were concerned about the methods being used to slaughter animals for food and the ways that cats and dogs were being destroyed. They also wanted to improve the welfare of animals by introducing reforms to livestock markets and transport facilities. Initially, the society set up a number of dispensaries for the animals of the poor and they established branches around the country.

One of these was in Torquay. The inaugural meeting, titled Justice for Animals, was held in early 1912. Significantly, this meeting was attended by those at the centre of Torquay society, and was held at Torre Abbey by invitation of Colonel and Mrs Cary.

This was a “large and representative gathering” presided over by Admiral Sir William Acland who stated that he was, “extremely fond of animals and tried at all times to show them every kindness”. He thought they, “deserved to be treated well and he was sure they would be if it was realised how acutely they felt pain and suffering”.

The main speech was by Dr Reinhardt of London, the chairman of the Council of Justice to Animals, who said he was there to, “challenge the right of humanity to make use of the lower animals or to eat animal flesh… Animals were akin to human beings in that they had a capacity for feeling pain, they had all the machinery and all the nerves and all the capacity for experiencing suffering that were possessed by the human being. There was still in very many parts of the country a callous disregard of this important fact.

“It was a century ago that Darwin had shocked man by making the discovery that the descent of man was not entirely unattached from an animal that travelled by other means than on its two legs. But since then an even greater discovery had been made – that the lower animals were able to feel an intensity of suffering to as great an extent as it seemed possible to get. They could see for themselves examples of the devotion, love, even unselfishness, which many animals possessed.”

A local branch of the CJA was then set up. It dedicated itself to, “the abolition of private slaughterhouses which were not open to public inspection and where many cruelties were practiced. The workers were frequently inexpert, made use of unsuitable instruments and often showed callous disregard for the suffering of the animals. Dwelling houses existed side-by-side with slaughterhouses. The slaughter was in public view and used by children as public entertainment.”

The CJA’s first aim was to replace the traditional method of slaughter, the pole-axe, with a mechanically operated humane stunner. Demonstrations were to be given to slaughter men and humane stunners were to be supplied to local tradesmen at low prices. As an indication of the meeting’s political influence, the President of the Torquay Master Butchers Association was in attendance and gave his support for the introduction of this, more humane, method of slaughter. To progress the adoption of the stun gun, the CJA advocated, what we would know today as, a consumer boycott whereby the public would be encouraged to only buy meat from animals that had been humanely killed.

Yet, Dr Reinhardt’s interests went beyond humane slaughter, and further than traditional Edwardian compassionate campaigning to an almost animal rights agenda. To a receptive audience, he mocked the rationale, still heard today, of those who were involved with hunting and fishing, “They had all heard the story of how the fox enjoyed the hunt as much as the hounds and how the fish delighted to dangle on the end of the hook.”

Returning to the original focus of this article, there’s a fascinating collection of correspondence between Georgina and her distant cousin Constance Wilde (1859-1898), the wife of Oscar Wilde (1854-1900) and the mother of his two sons.

When Constance became aware of her husband’s homosexual relationships is unclear, but by 1895 she would have known as Oscar (pictured above) was imprisoned for ‘gross indecency’. We know a great deal about the life of Constance and the effect that Oscar’s sexuality had on her through the many letters she exchanged with Georgina.

We’ve noted that Georgina was renowned for her philanthropy and that she became a public figure through her support for sanitary knowledge for women and for her anti-vivisection and vegetarianism. In the final decade of her life, she continued to provide comfort and inspiration to many people, one being Constance Wilde.

Between 1890-1898 hundreds of letters were exchanged between the two women and Georgina invited both Constance and Oscar to stay at her “pre-Raphaelite haven” of Babbacombe Cliff.

These letters came almost daily, for Constance could “not bear that a bit of me should not be with you every morning”. Letter writing became her, “island of refuge too for a few minutes in each day”. In her letters she wrote of her family life, telling Georgina about Oscar’s work, and she shared her life and thoughts. In one letter she confided that Wordsworth and Socialism were her “present hobbies”.

During Georgina’s visits to the “blessed gabled house” at Babbacombe the women read the Bible, Plato and Browning in the morning and Ruskin and novels in the afternoon and evening. After one three-month stay in Babbacombe, Oscar wrote to Georgina to thank her for letting them stay at a place which Constance, “so much loves, and where so much love has been given to her”.

Oscar would also visit Babbacombe Cliff without his wife and it was on one stay during the winter of 1892/93 that he completed his plays A Woman of No Importance, Salome and Lady Windemere’s Fan. Oscar and the children would feed the birds and he enjoyed exploring Torquay.

However, with Constance abroad, Oscar tempted young actors to join him. He wrote to Lord Alfred (Bosie) Douglas: “It is a lovely place, it only lacks you.” Bosie was on the next train to Devon. Bosie was, according to Wilde, a “gay, gilt and gracious lad… He lies like a hyacinth on the sofa, and I worship him.”

In April 1895, Bosie’s father, the Marquis of Queensberry, made allegations of homosexuality against Wilde. Oscar sued for libel, but lost. After details of his private life were revealed during the trial, Wilde was arrested and tried for gross indecency. Having been found guilty, he was sentenced to two years of hard labour in Reading Gaol.

Babbacombe provided Constance with a haven from this scandal – Georgina hoped that “Bab” would be an, “ark of refuge”. Constance (pictured below) wrote that the horror of visiting Oscar in prison was, “more awful than anything I have ever been through, and worse even for him I suppose”.

Nevertheless, although Georgina offered her home to Oscar as a place of refuge between his trials, she was also fearful of the social implications of association with the Wildes. A letter to a friend reads, “I do not think there could be a greater trial with such disgusting shame… one cannot bear even to allude to it. Can one touch pitch and not be defiled? You are quite right in keeping aloof – so would I if I did not feel called upon to shelter her.”

After the trial Constance changed her and her sons’ last name to Holland. However, the couple never divorced. She wrote to Georgina, “You once said to me that Love with you was synonymous with anguish but indeed Tennyson was right, although I used not to think so, when he said, ‘Tis better to have loved and lost than never to have loved’, and to have one’s love crushed and maimed is almost as if one had never loved at all, and I am utterly cold now and care not much for anything or anybody excepting of course for my boys …”

Upon his release, Oscar had left for France, never to return. He died destitute in Paris at the age of 46 in 1900. A fall down the stairs in the London home she had shared with her husband caused Constance to have a form of paralysis. She died on April 7 1898 after spinal surgery and is buried in Genoa.

The relationship between Oscar Wilde and Bosie was explored in the movie Wilde – starring national treasure Stephen Fry:

…