In 1865 Charlotte Winsor was arrested at her small cottage at Lawe’s Bridge – pretty much where MacDonald’s now stands.

On February 15 the body of Mary Jane Harris’ illegitimate four-month-old son had been found beside a road near Torre Station. The court later described the circumstances of the sad discovery of the child and the subsequent arrest: “The body was found wrapped in a newspaper sewn up with worsted. It might have been dead some days, for the weather had been extremely cold, and its appearance was compatible with its death having been caused either by exposure to the weather or by suffocation. It appeared to be about four months old, and by comparing this date with the Register of Births, the police were led to suspect that it was the illegitimate child of the servant-girl Harris, which had been placed with Winsor, who, with her husband and a little grand-daughter eight years old, lived in a retired cottage in the neighbourhood of Torquay.”

The charge was murder and the 45 year-old Charlotte Winsor (pictured below) quickly became the most famous baby farmer of her time.

Baby farming was a term used in Victorian England to mean the taking in of an infant or child for payment. And there was plenty of need for baby farmers in Torquay. The town was the wealthiest in England and the affluent needed a large servile class. Around 20% of the population were employed as domestic servants and women far outnumbered men by around a third. Yet for those women not able to secure employment, there were few alternatives and prostitution was a necessary source of income for many. ‘Sex workers’ consequently made up a significant proportion of Torquay’s female working class. While all communities had someone who would take in unwanted children, Torquay may have had a greater number of desperate women needing ‘child care’. This is where the baby farmer would come in.

Some baby farmers ‘adopted’ children for lump-sum payments, while others cared for infants for periodic payments. Baby farmers, usually middle-aged women, solicited through ‘adoption’ advertisements in newspapers, and through nurses, midwives, and the keepers of lying-in houses – these were private houses where women paid to give birth. Particularly in the case of lump-sum adoptions, it was more profitable for the baby farmer if the infant or child died and some adopted numerous children and then neglected them or murdered them outright. Several were tried for murder, manslaughter, or criminal neglect and were hanged, the last baby farmer being executed in Britain in 1907.

Though Trewman’s Exeter Flying Post described the pair as an “un-natural mother and the wretched murderess”, it may be that Charlotte was a victim of changing times. Baby farming was a part of life for many working class women, both urban and rural, and would generally be ignored. However, on 18 December 1848 Torre Railway Station had opened and Torquay was connected to the rest of the country – our days as a rural backwater were certainly over and accepted traditional practices were being seen in a new way.

What we know of the circumstances of the murder of the infant Thomas Edward Gibson Harris comes from his mother, 23 year old Mary Jane Harris. Mary, however, had turned Queens Evidence, where a criminal agrees to give information to to help convict another offender. Accordingly, as Mary was attempting to escape being hanged, she may not be an entirely objective witness. Nevertheless, at Exeter Assizes, her testimony revealed that Charlotte Winsor conducted a steady trade of boarding illegitimate infants for a few shillings a week or ‘putting them away’ (killing them) for a set fee of £3 to £5:

“In February last I was a servant at Mrs. Wansey’s, living at Tamar Villas, Torquay. Before I went there I had been confined of a male child. I took the child to Mrs. Winsor’s, near Shiphay Bridge, I had known her first some time in September at Marychurch. I made an arrangement with her to take care of the child. As I was going to Mrs. Winsor’s with the child we had some conversation. I said, ‘There has been one child picked up in the country.’ She said she had put away one of a girl who was confined at her house. The girl had promised to give her ₤3, but did not. I asked her how she did it. She said she put her finger on the jugular vein. She also said she had stifled one three weeks old for Elizabeth Sharland, and thrown it into Torbay, and when it was picked up it was nearly washed all to pieces. She said she had put away one for her sister Perry; that her sister said she would give her ₤4. Her sister had only given her ₤2 and had scarcely spoken to her since. That was all said on the way to the house. We had tea at her house. I asked her if she was not afraid. She said, ‘No; hell with you, it’s doing good;’ and that she would help any one that would never split upon her. I stayed with her half an hour, and as I was coming away she said, ‘I will do whatever lays in my power for your child.’ I said, ‘All right,’ and went away”.

On a subsequent visit, according to Mary the offer to kill the child for ₤5 was renewed: “She asked me then if she should do it. I asked how she could do it. She said, ‘Put it between the bedticks’ (bedticks were mattress bags, filled with stuffing such as feathers or straw for sleeping on). I don’t remember she said any more; but she took the child into the girl Pratt’s bedroom. I did not then go in, nor could I see what she did. She stayed there ten minutes, and then came back into the room without the baby. She said would I look in, and that it soon died. I looked in and saw the bed made up, but no child. During the time she was in the room the child did not cry. I saw the child’s body afterwards.”

The Guardian of August 2 gave its account of the inevitable sentence, “Winsor, who has a very forbidding countenance, took the proceedings at the late assizes very coolly, whilst Harris was much affected. Then Winsor began to look rather anxious, and her nervousness increased until she burst into a violent paroxysm of tears, from which she did not recover for between two and three hours.” In summing up Mr. Justice Keating said he, “seldom had heard more hideous revelations.” The jury retired, and after an hour and a half Charlotte Winsor was found to be guilty. His lordship then passed sentence of death upon the prisoner, “cautioning her not to hope for any mercy. The prisoner cried convulsively during the passing of the sentence.”

However, to the disappointment of the entrepreneurs who organised a day out to attend her hanging – with a visit on the way home to Newton Abbot Races thrown in – Charlotte Winsor escaped execution on a legal technicality. This was a close thing for Charlotte. Her grave had been dug and the hangman, a Mr. Calcraft, had twice visited Exeter to carry out the execution.

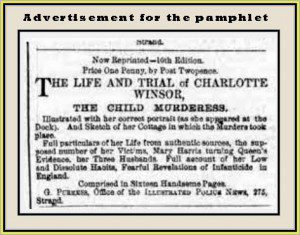

The Charlotte Winsor case certainly shocked Victorian Britain. A pamphlet of 1865 was titled: ‘The life and trial of the Child Murderess, Charlotte Winsor: Containing her correct portrait as she appeared in the dock, sketch of the cottage in which the murders took place, Trial at the Devon Assizes, Full Account of her low and Dissolute Habits, Account of her Three Marriages, supposed number of her victims, Fearful Revelation of Infanticide in England’.

The story became known across the Empire and remained of interest for many years. The Australian paper, The Queanbeyan Age in 1886 commented on, “The sensation caused by the case of Charlotte Winsor was extraordinarily great, it being proved on her trial at Exeter that she thrived on an organised system of child-murder. She was saved from the gallows by the fact that some technical points arising out of the case had to be argued before the Court for Crown Cases Reserved; and respite followed respite, it became generally believed that the terrors of suspense added to the punishment, and that penal servitude for the term of her natural life should be allotted. In the west of England both are still vividly remembered, furnishing material for talk for weeks to come at many a Devonshire fireside.”

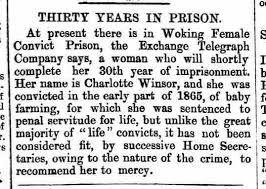

Charlotte Winsor died in prison of old age after serving almost 30 years. This was despite repeated attempts for her to be released on licence and assurances from her granddaughter that she would be cared for. The final petition for her release on May 5 1894 read that “she may spend the last of her days with her family”. The year before the Home Office had noted that Charlotte Winsor was among just five prisoners in England and Wales not to be released after serving 20 years.

The Winsor case did lead to change. The British Medical Journal published allegations in 1868 that baby farming was just a form of commercial infanticide – they claimed that the infants in the care of baby farmers were deliberately and severely neglected, leading to their deaths. The Torquay murder was used to illustrate a country-wide practice and to campaign for reform. Parliament began to regulate baby-farming in 1872 with the passage of the Infant Life Protection Act. A series of acts passed over the next seventy years, including the Children Act 1908 and the 1939 Adoption of Children (Regulation) Act, gradually placed adoption and foster care under the protection and regulation of the state.

If nothing else, the tragic death of little Thomas Harris in that remote Torquay cottage led to great improvements in child welfare across the nation and then the world.