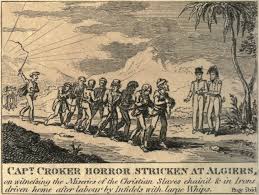

“…to the Fleece tavern to drink and there we spent till 4 a-clock telling stories of Algier and the manner of the life of Slaves there… those who have been slaves did make me full acquainted with their condition there. As, how they eat nothing but bread and water…. How they are beat upon the soles of the feet and bellies…” Samuel Pepys in his diary of 8 February 1661

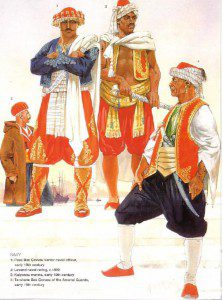

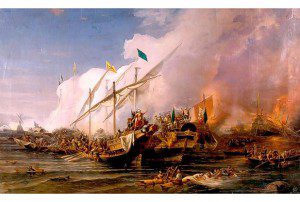

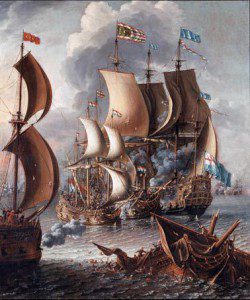

For over a hundred years Torbay was terrorised by Barbary pirates. During the seventeenth century all along the Devon coast these raiders burnt settlements, sank ships and carried off men, women and children into slavery. There were large numbers of pirates – in 1640 it was reported that there were 60 “Turkish men-of-war” off the South West coast. Our communities needed to keep a constant watch for the arrival of new sails in the Bay. Ironically, bearing in mind the image of pirates as hard-drinking men, the majority of the Bay’s pirates would consequently have been teetotal as they followed the Muslim faith.

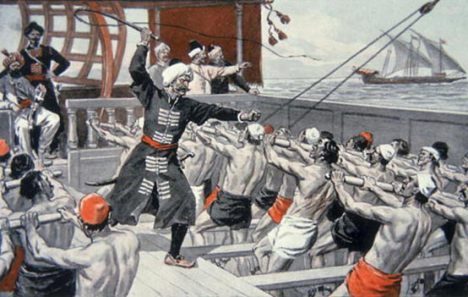

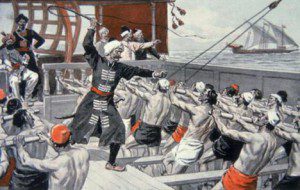

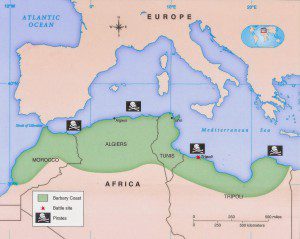

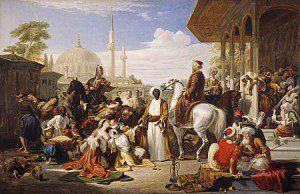

Sometimes called Ottoman corsairs, the Barbary pirates operated from North Africa and were based primarily in the ports of Algiers, Tunis and Tripoli. This was an area known as the Barbary Coast, from its Berber inhabitants. Along with seizing ships, they engaged in Razzias, raids on coastal towns. The main purpose of their attacks was to capture Christian slaves for the slave markets of North Africa.

The small rural communities that were to become Torbay feared these pirates with good reason. In August 1625 corsairs raided Mount’s Bay, Cornwall, capturing 60 men, women and children and taking them into slavery. In 1626 St Keverne was repeatedly attacked, and boats out of Looe, Penzance, Mousehole and other Cornish ports were boarded, their crews taken captive and the empty ships abandoned. In 1625 there was a petition to London from the wives of around 2,000 West Country sailors pleading for their ransom or rescue. For decades pirates anchored in the Bay and sailed out to attack ships in the Channel and to intercept fishing vessels returning from Newfoundland. In 1625 the Mayor of Poole wrote to the Privy Council demanding that protection be supplied for the ships returning from their Newfoundland fishing expeditions, “Twenty-seven ships and 200 persons had been taken by Turkish pirates in ten days”.

Admiralty records show that during this time the corsairs plundered English shipping at will, taking 466 vessels between 1609 and 1616 – 27 vessels from near Plymouth were lost in 1625 alone. There were also tales of pirate cruelty. It was said that when forced into Devon ports in bad weather the pirates would throw their prisoners overboard and pretend to be honest captains of a foreign power.

While we don’t have accurate records of how many people were taken, around 8,500 new slaves were needed annually to replenish numbers. Therefore, from the 16th to 19th century, corsairs captured an estimated 800,000 to 1.25 million people as slaves – more than 20,000 captives were said to be imprisoned in Algiers alone. Most came from Christian countries nearer to the African shore, but an estimated 1,500 a year were taken from the South West and Ireland during the 17th century peak. The English accordingly became familiar with captivity narratives written by the Barbary prisoners as so many people were taken. Most captured folk ended their days as slaves in North Africa, dying of starvation, disease, or maltreatment.

While many converted to Islam to escape from the galleys where they were forced to row for years, they still remained as property.

For the more affluent captives it was possible to return to England. This was, however, on the payment of a ransom. To pay these ransoms regular fundraising was undertaken by families and local church groups. The clergy had the role of negotiating with slave owners – ‘Lazarist Priests’ took up permanent posts in Algiers and Tunis. In 1660 an influential committee (including the Archbishop of Canterbury and Bishop of London) was formed which focused on raising ransoms. Money would be raised during sermons and Churchwardens would “visit every household within reach” to collect donations.

On the other hand, the Church chose who it rescued. ‘Renegades’ were slaves who had converted to Islam through force, choice or convenience and would not be ransomed. As Christian women who worked in the harem often “turned Turk” to stay with their children who were being raised as Muslims, these were also exempt from Church charity. Sermons preached that it was better to die a Christian martyr than live as a Turk.

The attacks couldn’t be tolerated in the long term. They threatened the region’s fishing industry and the English state itself. Oliver Cromwell, alarmed that the pirates were crippling ports and damaging the English merchant fleet, decreed that any captured ‘Arab’ should be taken to Bristol and slowly drowned. He also commissioned Robert Blake and William Penn to clear the pirates off their base on Lundy Island.

The pirate stronghold was bombarded and those not killed or captured fled back to North Africa. Despite this, pirates continued to mount raids on the coastal communities of Cornwall, Devon and Dorset.

The European nations finally responded by attacking the pirates in their home bases. In 1675 a Royal Navy squadron negotiated a lasting peace with Tunis and, after bombarding the city to induce compliance, with Tripoli. Algiers was frequently attacked by the British, French and Spanish and, in the early 19th century, the United States. After another British-led attack in 1816 more than 4,000 Christian slaves were released and the power of the Barbary pirates was finally destroyed by European sea power.

Yet for 300 years coastal communities around the Mediterranean and the British Isles saw depopulation and impoverishment caused by the kidnapping of breadwinners. Millions were paid by the already poor inhabitants of villages and towns to see the return of their own people.

Here’s the song ‘Lily of Barbary’, telling of the trade in human lives:

……………