For over two-hundred years Berry Pomeroy Castle has been a focus of fascination for those searching for mystery and romance.

Though the castle is owned by John Seymour, 19th Duke of Somerset, it is administered by English Heritage; and the charity’s guidebook somewhat reluctantly recognises the site as being “reputed to be one of the most haunted castles in Britain.”

Generations of locals and tourists have consequently visited the castle with the aim of experiencing the supernatural.

So, what were the influences that made Berry Pomeroy Castle Torquay’s paranormal playground?

A primary cause of the castle’s fame was location. At around seven miles from Torquay, it was conveniently close enough to the resort for a day trip by horse-drawn carriage and later by motor coach or car.

But also, over the past 250 years the castle functioned as an ideal expression for a series of cultural trends.

But also, over the past 250 years the castle functioned as an ideal expression for a series of cultural trends.

The first of these was an enthusiasm for landscape painting which grew through the second half of the eighteenth century. This gives us the word ‘Picturesque’ to describe a type of countryside view that had an artistic appeal. In 1782 William Gilpin instructed leisured travellers to examine “the face of a country by the rules of picturesque beauty”. The ideal was that such landscapes should be beautiful but also have some elements of wildness.

Castles subsequently became celebrated as examples of the Picturesque. And so, after lying in ruins for a hundred years, Berry Pomeroy, atop a limestone crag above the Gatcombe Brook, became a popular tourist attraction.

Castles subsequently became celebrated as examples of the Picturesque. And so, after lying in ruins for a hundred years, Berry Pomeroy, atop a limestone crag above the Gatcombe Brook, became a popular tourist attraction.

We also have the influence of Romanticism, an artistic and intellectual movement most popular from around 1800 to 1850. Partly a reaction to the Industrial Revolution and the Age of Enlightenment, Romanticism emphasised emotion and individualism and glorified the past and nature. To access dramatic vistas without relinquishing modern comforts, tourists could take a short break from the hustle and bustle of a modern town into an idealised version of medieval history.

A further attraction was the possibility of encountering the supernatural. Visitors were aware of the paranormal potential of a castle as they were familiar with Gothic literature, having access to novels, magazine short stories, and cheap ‘penny dreadfuls’.

Taking a lead from Shakespeare’s tragedies, Gothic narratives were typically set in physical reminders of the past, especially structures that stood as evidence of a place once full of life, but now decaying, where dark secrets lay hidden. Castles were ideal settings for the hauntings, murders, mystery, and intrigue of the genre.

The first Gothic work was Horace Walpole’s hugely popular 1764 novel ‘The Castle of Otranto’, presented as a translation of a sixteenth century manuscript. This was followed by many other Gothic novels, such as Ann Radcliffe’s 1794 ‘The Mysteries of Udolpho’ which also used a castle as a setting. Later Romantic poets and novelists such as Walter Scott and Mary Shelley, who in 1815 visited Torquay with her husband Percy Bysshe Shelley, drew on Gothic motifs.

The first Gothic work was Horace Walpole’s hugely popular 1764 novel ‘The Castle of Otranto’, presented as a translation of a sixteenth century manuscript. This was followed by many other Gothic novels, such as Ann Radcliffe’s 1794 ‘The Mysteries of Udolpho’ which also used a castle as a setting. Later Romantic poets and novelists such as Walter Scott and Mary Shelley, who in 1815 visited Torquay with her husband Percy Bysshe Shelley, drew on Gothic motifs.

In 1806 Edward Montague, author of ‘The Demon of Sicily’ and ‘Legends of a Nunnery’, brought the Gothic to Devon. In his novel ‘The Castle of Berry Pomeroy’ he adapted local folk tales into a saga of horror, jealousy, and revenge.

The plot has Lady Elinor de Pomeroy becoming envious of her beautiful 18-year-old sister, Matilda, who has inherited the castle and the love of the handsome De Clifford. Deciding to have her murdered, Elinor enlists the aid of evil Father Bertrand in the dirty deed. Matilda’s spectre, however, haunts Elinor and Bertrand and the body count rises. Yet, this is all a misdirection. Matilda, was alive all the time, though confined to a tower, and all is well. This is fiction, there is no record of an Elinor and Matilda de Pomeroy. In later tellings, Matilda, a common name in Gothic narratives, becomes Margaret and, as she is dressed in white, becomes the benign White Lady ghost.

The plot has Lady Elinor de Pomeroy becoming envious of her beautiful 18-year-old sister, Matilda, who has inherited the castle and the love of the handsome De Clifford. Deciding to have her murdered, Elinor enlists the aid of evil Father Bertrand in the dirty deed. Matilda’s spectre, however, haunts Elinor and Bertrand and the body count rises. Yet, this is all a misdirection. Matilda, was alive all the time, though confined to a tower, and all is well. This is fiction, there is no record of an Elinor and Matilda de Pomeroy. In later tellings, Matilda, a common name in Gothic narratives, becomes Margaret and, as she is dressed in white, becomes the benign White Lady ghost.

The ghostly element of Montague’s novel seems to have its origin in an actual recorded experience. This gives us a second ghost, this time vengeful and malevolent.

It comes from the 1790s memoirs of Dr Walter Farquhar. During a visit to a sick woman, he briefly encounters the apparition of a “richly dressed lady”, a harbinger of death. In later stories, the woman, dressed in blue and so known as the Blue Lady, is said to beckon for help from passers-by, usually men, luring them to a tower where they fall to their death.

The Blue Lady is identified as the daughter of a Norman lord who was the father of her baby. She strangles the baby and has since wandered the castle mourning her loss and taking revenge on random male visitors. Incest has been a Gothic trope from its very beginnings, Walpole’s ‘Otranto’ utilising the threat of incestuous rape as a danger from which the heroine needs to defend herself.

Undermining the Blue Lady story is the long-held assumption that the castle was early medieval, ruled by a Norman baron, and so presumably built between 1066 and 1154. However, the castle has fairly recently been identified as dating from the late fifteenth century.

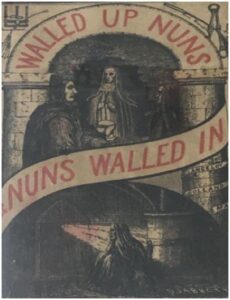

These are then the two ghosts that are said to haunt the castle, the White and the Blue Ladies, though their stories often get confused to become one. There is also a later addition that has the White/Blue Lady, in that most medieval of punishments, being walled up in the castle’s dungeon to starve to death. The Early Modern Berry Pomeroy doesn’t have a dungeon. It may also be worth noting that Walter Scott’s 1808 poem ‘Marmion’ has a nun walled alive inside a convent.

These are then the two ghosts that are said to haunt the castle, the White and the Blue Ladies, though their stories often get confused to become one. There is also a later addition that has the White/Blue Lady, in that most medieval of punishments, being walled up in the castle’s dungeon to starve to death. The Early Modern Berry Pomeroy doesn’t have a dungeon. It may also be worth noting that Walter Scott’s 1808 poem ‘Marmion’ has a nun walled alive inside a convent.

White Lady ghosts, typically dressed in that colour, are found in many countries around the world. Common to many of these legends is an accidental death, murder, or suicide, and the theme of loss, betrayal by a man, and unrequited love. Thirteen legends across England describe White Lady ghosts as the victims of murder or suicide who die before they can reveal the location of hidden treasure.  The castle is also supposedly haunted by the spirits of two young brothers. Facing defeat and the loss of their castle during a siege, they don full armour, spur their horses to the top of the castle ramparts to together plunge to their deaths. There is no account or evidence of the castle having faced any attack and full armour would be an anachronism at the time the castle was constructed. Romantic suicide was a common theme in Gothic tales.

The castle is also supposedly haunted by the spirits of two young brothers. Facing defeat and the loss of their castle during a siege, they don full armour, spur their horses to the top of the castle ramparts to together plunge to their deaths. There is no account or evidence of the castle having faced any attack and full armour would be an anachronism at the time the castle was constructed. Romantic suicide was a common theme in Gothic tales.

There is no question that people see things they can’t explain and there are many reports of odd goings-on at Berry Pomeroy. As a rule, however, the more ‘back-story’ a legend has, the less likely it is to reflect a genuine experience and is therefore probably a Georgian or Victorian invention.

By the early nineteenth century, the Gothic had ceased to be the dominant genre for novels in England. Yet, Charles Dickens, another Torquay visitor, was influenced by Gothic novels as a teenager and incorporated their atmosphere and melodrama into his works. Furthermore, castles have continued to be a feature of horror literature, the most memorable being Bram Stoker’s 1897 ‘Dracula’.

An appetite for faux supernatural thrills throughout the nineteenth century was to be found in the new and rapidly growing resort of Torquay. From a population of 838 in 1801, Torquay slowly developed as a health resort and then rapidly expanded when the railway arrived in 1848. By 1851 the population was 11,474, and by the beginning of the twentieth century had reached over 33,000. Many tens of thousands more arrived each year as short- and long-term tourists.

An appetite for faux supernatural thrills throughout the nineteenth century was to be found in the new and rapidly growing resort of Torquay. From a population of 838 in 1801, Torquay slowly developed as a health resort and then rapidly expanded when the railway arrived in 1848. By 1851 the population was 11,474, and by the beginning of the twentieth century had reached over 33,000. Many tens of thousands more arrived each year as short- and long-term tourists.

During the early 1900s Torquay would claim to be the richest town in in the country, its architectural style replicating the buildings, gardens, and parks of the Mediterranean. In 1862 Charles Dickens wrote, “Torquay is a pretty place… a mixture of Hastings and Tunbridge Wells and little bits of the hills about Naples”. Ruskin would carry on the theme and call Torquay, “The Italy of England”. It would then adopt the title of the English Riviera.

Italy was the Gothic authors preferred geographical and historical background, a place of violence and passion ruled by a cruel feudal nobility allied to a corrupt Catholic clergy. Torquay could then offer a themed vacation of a few hours, to both a sunnier European place and to another more romantic time.

During the nineteenth and twentieth centuries Torquay moreover acquired a deserved reputation for being a centre of occult thought and practice. The town’s large population of the educated and wealthy had a great deal of time on their hands, an environment that stimulated an interest in spiritualism, the supernatural, and a variety of pseudo-scientific theories and practices.

This other side to the daylight of the rational was darkly reflected by an outpouring of literature exploring the uncanny, with many of the great writers on the macabre and mysterious having associations with the town. The Shelleys and Dickens visits have already been mentioned. Alongside these great authors came: Robert Louis Stevenson (‘Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde’); Edward Bulwer-Lytton (‘The Haunters and the Haunted’); Arthur Conan Doyle (‘Sherlock Holmes’); TS Eliot (‘The Waste Land’); Rudyard Kipling (‘Tales of Horror’); Oscar Wilde (‘Dorian Gray’); Wilkie Collins (‘The Woman in White’); Henry James (‘The Figure in the Carpet’); and many others.

Carriages touted for custom at the Strand

All visitors, famous or otherwise, expected to be entertained. Carriages waiting at the Strand or collecting from the hotels and villas offered a day out from the mundane. This was a competitive industry and so guides had an incentive to invent, import, and embellish the stories they told their paying customers. The greater the excitement, the higher the gratuities.

These were the influences and local folk stories that, for over two-hundred years, transformed a fairly unexceptional ruin into Torquay’s paranormal playground, a focus for those searching for a frisson of mystery, romance, and supernatural excitement. Regardless of the slight embarrassment to some ‘serious’ historians, that fascination continues into the supposedly rational twenty-first century.

‘Torquay: A Social History’ by local author Kevin Dixon is available for £10 from Artizan Gallery, Lucius Street, Torquay, or:

https://www.art-hub.co.uk/product-page/torquay-a-social-history-by-kevin-dixon