“So after dark, you kids be good

Stay at home, the way that you should

‘Cause right outside, and waitin’ there

Is the Headless Horseman. Beware!

And I’m gettin’ out of here”.

The Headless Horseman, Bing Crosby (1949)

Between Torre Station and Torre Abbey Gates lies Avenue Road – one of the oldest thoroughfares in what would become our Torquay. It led away from Torre Abbey, founded in 1196, to the ‘New Town of the Abbots’ which was given the right to hold a weekly market on Wednesdays sometime between 1247 and 1251.

As with all ancient places, the Abbey has acquired stories about ghosts. We’ve covered the most well known on WASD before – the Spanish Lady who, disguised as a boy sailor, died in the in the overcrowded Spanish Barn in 1588.

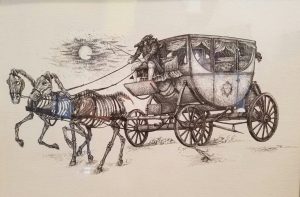

There are others. The Abbey’s Lady Cary is supposed to wear a magnificent ball gown and travel in a spectral illuminated coach and horses along Avenue Road. However, the Cary family occupied the Abbey between 1662 and 1930 and the legend doesn’t tell us which Lady Cary tarried after death and why. As there isn’t a particular tragedy associated with a specific Lady Cary we don’t have an obvious suspect so can’t pin down the date the story began circulating.

Another spirit is that of a headless young priest who, it is said, gallops up and down Avenue Road on a ghostly steed. Henry VIII’s Dissolution of the Abbey and the exile of Catholic priests took place in 1539 so folk memory would have the supposed beheading before that date. Indeed, one part of the priest’s demise narrative gives a date of “around the 1300s”. Yet, in some tellings the two legends, of the headless priest and the haunted coach, seem to have been blended and we now have tales of a coach with a headless driver haunting Avenue Road.

The stories of Headless Horseman aren’t unique to Torquay, however. They have been around in European folklore since at least the Middle Ages, where the horseman is traditionally depicted as a man on horseback either carrying his own head, or it’s missing and he’s searching for it. The German Legends of the Brother Grimm, for instance, recount German folk tales of headless horsemen.

The most famous retelling though comes in the short story ‘The Legend of Sleepy Hollow’ written in 1820 by Washington Irving. You’ve probably seen the Tim Burton 1999 film ‘Sleepy Hollow’ with Johnny Depp. The story is based on a traditional folktale that during the American Revolutionary War the Horseman was a Hessian artilleryman decapitated by an American cannonball. Each Halloween night he rises as a malevolent ghost, furiously seeking his lost head. Below is ‘The Headless Horseman Pursuing Ichabod Crane’ by John Quidor (1858).

And we do know that Torquay folk borrowed supernatural stories from other places. In Irish folklore the Headless Horseman is dullahan (‘dark man’) who wields a whip made from a human corpse’s spine and identifies those about to die. In another version, he is the headless driver of a black carriage. In Ballymena (County Antrim) a robber escaping from a house was said to have ridden into a thin wire between the gateposts… his decapitated spirit is still to be seen at Halloween. Irish navvies helped build Torquay’s railways between 1848-59 so they could have brought stories of the dullahan with them. On the other hand, Torquay also had plenty of visitors from north of the border – in Scotland, one headless horseman was called Ewen who was decapitated in a clan battle on the Isle of Mull.

Or perhaps closer to home. The Isle of Wight has the wild hunt, the supernatural cavalry that rode across the sky, along with headless horsemen out on the toll road and phantom coaches with headless drivers. In Abington (Northamptonshire) a man, racked with guilt after deliberately running over his daughter’s lover in 1780, continues to drive his coach and horses down the lane, though he has lost his head. In Aylsham (Norfolk) a ghostly coach passes over eleven bridges once a year, driven by a headless Sir Thomas Boleyn on the night of his daughter Anne’s execution.

Scooby Doo meets the Headless Horseman

And there is a famous Devon story. Okehampton Castle has the ghost of Lady Howard, well known for her killing spree in which she slaughtered her four husbands. Legend has it that ever since her passing, every night she travels from Okehampton to Tavistock and back in a carriage made of bones that’s driven by a headless driver. She is punished by being compelled to pick one strand of grass from the hill and then returning home again – it is only once the hill is stripped completely bare of its grass that she will have her punishment lifted. The ryme goes:

“My lady hath a sable coach,

And horses two and four;

My lady hath a black blood-hound

That runneth on before.

My lady’s coach hath nodding plumes,

The driver hath no head;

My lady is an ashen white,

As one that long is dead.”

Another possible prompt for these many tales and legends of phantom coaches was that, during the early modern period, roads were badly maintained and dangerous. Even when turnpikes were introduced making the roads safer in the 18th century, many road accidents happened. Roads were places of death and tragedy.

Or we could be looking at a more earthly root for the legend of Torquay’s Headless Horseman. Of course, Headless Horsemen don’t haunt busy thoroughfares – they would be seen! They infest lonely rural roads and Avenue Road was just that. The Torquay Turnpike Act to repair our roads came in 1823 and the Ordnance Survey of 1861 still shows Avenue Road (pictured above) as an avenue of trees set in fields with no housing. From the early nineteenth century come many reports of our local smuggling gangs and how they evaded the Revenue Men. Rural Torquay roads were considered to be haunted and this undoubtedly aided our smugglers. We have, for example, the Brandy Bottle Tree in Kingskerswell on the Barton Hall estate which was a regular cache for spirits which were conveyed from the coast in a hearse which was painted with luminous paint. It was further reported that, “At Brixham there was a man who took the brandy inland: this he did with a hearse painted with phosphorous; the horses had their feet padded in order to travel quietly, and the driver was got up as the Devil himself. When this conveyance was on the road everybody fled from it in terror”. It was also “remembered in Paignton that the horses’ heads were sometimes covered with black sacks to make them appear headless.”

So did local smugglers put the story about that it was best to stay indoors at night?

Or is there a deeper psychological explanation? Beheading has always symbolised the exercise of absolute power and it also strikes at power – the formalised beheading of King Charles still haunts the English imagination. The late Victorians were obsessed with the threat to male power and potency through stories of symbolic decapitation by a femme fatale. And, of course, we have Sigmund Freud, who saw decapitation as a displaced symbol of the anxiety about castration. While Freud was writing at the turn of the 20th Century there were many plays and paintings about Salomé, the dancer in the Bible who demands John the Baptist’s head, served on a platter – Torquay resident Oscar Wilde’s version is the most famous of these.

Whatever the inspiration for Torquay’s Headless Horseman, it’s best, perhaps, to be safe, and not sorry. So beware when you walk Avenue Road late at night and heed the advice of Bing Crosby:

You can join us on our social media pages, follow us on Facebook or Twitter and keep up to date with whats going on in South Devon.

Got a news story, blog or press release that you’d like to share or want to advertise with us? Contact us