In May 2022 a local newspaper ran an article, “What life is really like in Torquay ‘no go’ district blighted by drugs”. The piece began with, “It should be the grand civic square outside Torbay Council’s HQ” and then continued with a catalogue of misery about Castle Circus.

Over the years Castle Circus has become representative of social and economic changes that have taken place across Britain. From green fields to commerce, to civic authority, this convergence of roads became the focus of the town’s self-doubt, a dark nostalgia about how the resort has deteriorated to become, for some, an inner city-by-the-sea.

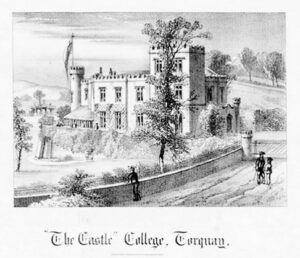

So how did we get here? First of all, there isn’t a castle at Castle Circus. The appellation began in the late 1830s when a large crenelated villa, The Castle, was built on Furze Hill overlooking the valley. The house is still there and home to overseas students.

First of all, there isn’t a castle at Castle Circus. The appellation began in the late 1830s when a large crenelated villa, The Castle, was built on Furze Hill overlooking the valley. The house is still there and home to overseas students.

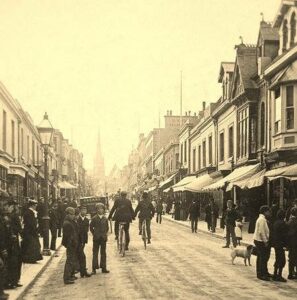

Torquay, often called ‘Little London’ by Victorian visitors, borrowed names from the capital. And so, the town adopted ‘circus’, the round intersection of Piccadilly where streets joined in a circle.

Torquay, often called ‘Little London’ by Victorian visitors, borrowed names from the capital. And so, the town adopted ‘circus’, the round intersection of Piccadilly where streets joined in a circle.

As Torquay rapidly expanded during the mid-nineteenth century, housing and commercial developments filled in the gap between the medieval settlement of Tormohun and the new tourist-focussed harbourside. Here were to be found homes and businesses, including furniture warehouses and Morgan’s Nursery, remembered in Morgan Avenue. Another well-known supplier, White & Co., ‘The Exchange & Mart Dealer’, was superseded in 1935 by the Borough of Torquay Electricity Department’s Art Deco ‘Electric House’.

As Torquay rapidly expanded during the mid-nineteenth century, housing and commercial developments filled in the gap between the medieval settlement of Tormohun and the new tourist-focussed harbourside. Here were to be found homes and businesses, including furniture warehouses and Morgan’s Nursery, remembered in Morgan Avenue. Another well-known supplier, White & Co., ‘The Exchange & Mart Dealer’, was superseded in 1935 by the Borough of Torquay Electricity Department’s Art Deco ‘Electric House’.

The private houses and artist workshops of Tor Church Road were soon converted by building over front gardens to create small retail premises. Older locals still remember the toy shops and tourist outlets.

The private houses and artist workshops of Tor Church Road were soon converted by building over front gardens to create small retail premises. Older locals still remember the toy shops and tourist outlets.

Further enhancing the urban landscape was the 1849 construction of the Church of St Mary Magdalene and the nearby Dispensary and Infirmary which opened in 1851. Both are still extant, though the hospital is now apartments.

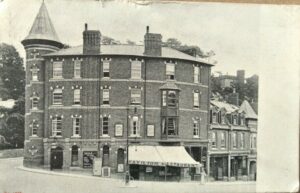

Further enhancing the urban landscape was the 1849 construction of the Church of St Mary Magdalene and the nearby Dispensary and Infirmary which opened in 1851. Both are still extant, though the hospital is now apartments. The Castle Circus we now know is largely the product of the early twentieth century. It was designed to underpin Torquay’s reputation as the richest town in England and the epicentre of the British Empire at leisure. The resort had, thus far, been successful but was well aware of its rivals’ ambitions. And so, while the original Italianate Abbey Road Town Hall was befittingly reminiscent of small-town Tuscany, it could no longer be relied on to inspire in a new century. A more impactful initial impression was required at the gateway to the town.

The Castle Circus we now know is largely the product of the early twentieth century. It was designed to underpin Torquay’s reputation as the richest town in England and the epicentre of the British Empire at leisure. The resort had, thus far, been successful but was well aware of its rivals’ ambitions. And so, while the original Italianate Abbey Road Town Hall was befittingly reminiscent of small-town Tuscany, it could no longer be relied on to inspire in a new century. A more impactful initial impression was required at the gateway to the town.

An opportunity came in 1898 when the Flete Brook was confined to a culvert, allowing the construction, between 1906 and 1913, of a Baroque Town Hall. Even though the building was already somewhat out-of-date, the highly decorative and theatrical Baroque maintained Torquay’s Mediterranean pretensions.

An opportunity came in 1898 when the Flete Brook was confined to a culvert, allowing the construction, between 1906 and 1913, of a Baroque Town Hall. Even though the building was already somewhat out-of-date, the highly decorative and theatrical Baroque maintained Torquay’s Mediterranean pretensions.

The design had its origins in the churches and palaces of seventeenth century Catholic Europe, the aim being to inspire awe as a counter to the Reformation. The English Baroque similarly favoured tradition and order, became closely associated with Toryism, and was a way to resist unwelcome social change. Here was a massive monument that insisted that Torquay’s great days of being the nation’s premier resort would be defended to the last.

The design had its origins in the churches and palaces of seventeenth century Catholic Europe, the aim being to inspire awe as a counter to the Reformation. The English Baroque similarly favoured tradition and order, became closely associated with Toryism, and was a way to resist unwelcome social change. Here was a massive monument that insisted that Torquay’s great days of being the nation’s premier resort would be defended to the last.

Just yards away from Castle Circus was Torquay’s industrial and working-class district. As the name suggests, Factory Row was a centre for manufacturing. The remains of pottery kilns can still be seen high up on the walls beneath the multi-storey flyover. Alongside workshops were beer houses and the Baptist Chapel, now a community café.

Just yards away from Castle Circus was Torquay’s industrial and working-class district. As the name suggests, Factory Row was a centre for manufacturing. The remains of pottery kilns can still be seen high up on the walls beneath the multi-storey flyover. Alongside workshops were beer houses and the Baptist Chapel, now a community café.

Thus was created a town of two halves. Municipal power, commerce, and industry at the top of town, and frivolity and leisure around the Strand.

Higher and Lower Union Street and its adjacent lanes consequently became a locals’ space. By the latter years of the twentieth century here were clustered pubs and clubs: The Hideaway, Doodles, The Trades Club, Peacocks Cocktail Bar, The Wig & Pen, The White Hart, and the Hop & Grapes. Castle Circus was even considered to be a safe environment for young foreign students to gather as darkness fell, in contrast to the often-rowdy harbourside.

Higher and Lower Union Street and its adjacent lanes consequently became a locals’ space. By the latter years of the twentieth century here were clustered pubs and clubs: The Hideaway, Doodles, The Trades Club, Peacocks Cocktail Bar, The Wig & Pen, The White Hart, and the Hop & Grapes. Castle Circus was even considered to be a safe environment for young foreign students to gather as darkness fell, in contrast to the often-rowdy harbourside.

A wistfulness for this long-gone Castle Circus has swollen into a much greater nostalgia. But what transformed the town centre wasn’t the sudden arrival of the ill-disciplined, the addict, and the work-shy, but irresistible changes to the ways that we live, shop, and acquire an income.

A wistfulness for this long-gone Castle Circus has swollen into a much greater nostalgia. But what transformed the town centre wasn’t the sudden arrival of the ill-disciplined, the addict, and the work-shy, but irresistible changes to the ways that we live, shop, and acquire an income.

Between the 1960s and 80s, most British town and city centres saw the development of a shopping precinct; Torquay’s was the relatively small Haldon Centre, built in 1981 and now named Union Square. Then came the proliferation of out-of-town shopping centres; the Willows was built in the early 1990s. Such new shopping opportunities were established on the edge of older communities, privatised, and policed. You don’t get street-people outside Sainsbury’s.

Between the 1960s and 80s, most British town and city centres saw the development of a shopping precinct; Torquay’s was the relatively small Haldon Centre, built in 1981 and now named Union Square. Then came the proliferation of out-of-town shopping centres; the Willows was built in the early 1990s. Such new shopping opportunities were established on the edge of older communities, privatised, and policed. You don’t get street-people outside Sainsbury’s.

The second challenge to the traditional High Street was online shopping. The first World Wide Web server and browser was only created in 1989, with subsequent technological innovations throughout the 1990s. Amazon launched its online shopping site in 1995 while eBay was introduced the same year.

The second challenge to the traditional High Street was online shopping. The first World Wide Web server and browser was only created in 1989, with subsequent technological innovations throughout the 1990s. Amazon launched its online shopping site in 1995 while eBay was introduced the same year.

These twin challenges saw many shops and banks close their doors while the larger retailers relocated to the periphery of the Bay. And so, we witnessed the remodelling of Castle Circus. Three sites are perhaps most illustrative of this: the cinema; the homeless hostel; and the Castle Inn.

In 1933 the Regal Cinema opened opposite the Town Hall. It was admired for its auditorium where scenes of local beauty spots were painted on the sidewalls. The cinema, also used at times as a bingo hall, finally closed in 1987 and was demolished in 1989. It was replaced by an office block named Regal House in 1995 and became home to a Job Centre Plus.

In 1933 the Regal Cinema opened opposite the Town Hall. It was admired for its auditorium where scenes of local beauty spots were painted on the sidewalls. The cinema, also used at times as a bingo hall, finally closed in 1987 and was demolished in 1989. It was replaced by an office block named Regal House in 1995 and became home to a Job Centre Plus.

This was a significant shift in the function and public perception of Castle Circus. The Victorians had assiduously hidden the poor in the town’s backstreets, even issuing visitors with guides about which areas to avoid. Throughout the twentieth century employment offices had also been discreetly placed out-of-sight. Now the new Job Centre was in the most prominent of places. This was a conspicuous transition from middle-class entertainment to provision for the poor, particularly as Job Centres incrementally became more managers of the marginalised than finders of full-time employment.

Nearby came other health and social care services for the increasing number of people needing support for their mental health and substance abuse. Later would come the churches and charities of Castle Circus, providing food as more fell into poverty.

At the end of Factory Row was once a successful social club for local workers. In the early 1980s this building became the Torquay Unemployed Centre, offering support for the increasing numbers of jobless as the deindustrialisation of Britain gathered pace. In 1991 the building became a homeless hostel, the Leonard Stocks Centre, which was re-developed in 2009 at a cost of £2million. Thirty-two people with complex needs could be accommodated at the centre, but the offer of companionship then attracted others to the vicinity.

At the end of Factory Row was once a successful social club for local workers. In the early 1980s this building became the Torquay Unemployed Centre, offering support for the increasing numbers of jobless as the deindustrialisation of Britain gathered pace. In 1991 the building became a homeless hostel, the Leonard Stocks Centre, which was re-developed in 2009 at a cost of £2million. Thirty-two people with complex needs could be accommodated at the centre, but the offer of companionship then attracted others to the vicinity.

Then we have The Castle, arguably Torquay’s oldest pub. In 1837, alongside new houses on Tor Church Road, Joseph Reed opened the Castle Inn in Binney’s Orchard. This remained a popular free house and by the 1970s was even described as “the most valuable public house in south Devon” with annual sales of 1,436 barrels of draft beer and 223 barrels of bottled beer. The inn contained a public bar, off licence, the ground floor Castle Lounge, a basement lounge bar, a disco, and three staff flats. Ready to cater for new tastes, in 1981 the Castle opened Plonkingtons’ Wine Bar.

By 1992, however, The Castle was reflecting the altered state of Castle Circus and was named as “a drug troubled pub”. It was relaunched under the name Chaplin’s Cafe Bar but in 2008, after 171 years, the pub was closed. It later reopened though the clientele and reputation had much altered since it was the resort’s most popular high-class venue. No longer do most locals rendezvous at the Castle.

By 1992, however, The Castle was reflecting the altered state of Castle Circus and was named as “a drug troubled pub”. It was relaunched under the name Chaplin’s Cafe Bar but in 2008, after 171 years, the pub was closed. It later reopened though the clientele and reputation had much altered since it was the resort’s most popular high-class venue. No longer do most locals rendezvous at the Castle.

Torquay has always had a predominantly low-wage, low-skill economy reliant on the seasonal tourism industry. This contributed to pockets of significant poverty and deprivation. Yet, for decades the resort offered employment in a sort of extended holiday before ‘real jobs’ would be taken up in Britain’s industrial heartlands by returning workers. During the 1980s, however, those jobs disappeared and for many there was nothing to go back to. Meanwhile, the erosion of communities across Britain led to more rootless people finding their way to Britain’s coastal towns.

Social change is usually incremental and mostly unnoticed. Though if we are searching for a point in time when the town centre shifted in focus, we have Mike Williams’ record of Torquay’s counterculture. Here we find an origin narrative for some of those vulnerable people we encounter on the streets.

Mike chronicles a transition from early 1960s optimism to later hopelessness. He further gives a specific date of 11 June 1965, the day local hippies attended the ‘Wholly Communion’ poetry event at London’s Albert Hall. This experience, he writes, markedly determined the direction of the movement, particularly towards the embrace of narcotics:

“There was a noticeable decline in this almost paradisiacal lifestyle from 1965 onwards. Beatnik was dead, hippy was in, and the innocence and joy of being young in Torquay was lost forever. The scene degenerated into drunkenness and despair, reflecting that of the underground Torquay youth culture as a whole. In the end the scene collapsed completely. Mandrax, LSD, and heroin took a greater hold.”

Another event that influenced the outlook of a generation was the 1969 police drugs raid on Belgrave Road’s Rising Sun. When seventeen young people were arrested this set the scene for decades of conflict between the authorities and alternative Torquay. In consequence, as the sixties ended, the mood noticeably changed. In 1972 a hundred-strong mob of men and women attacked Torquay police station, throwing bricks and bottles.  Most of those we come across are, on the other hand, incomers. It took forty years to transform Castle Circus into an enclave for the peripatetic underclass, a reservation for the residuum in a de facto toleration zone. “Build it; and they will come.” We did and they did.

Most of those we come across are, on the other hand, incomers. It took forty years to transform Castle Circus into an enclave for the peripatetic underclass, a reservation for the residuum in a de facto toleration zone. “Build it; and they will come.” We did and they did.

Torquay now attracts street people to a place of relative safety, where: accommodation is possible in Factory Row or nearby bedsits; with health, welfare, and pharmaceutical services on offer; alcohol and illicit drugs at hand; an unpoliced multi-story car park in which to consume them; set against a backdrop of an alternative economy of petty crime.

Torquay now attracts street people to a place of relative safety. Castle Circus is where accommodation is possible in Factory Row or nearby bedsits; with health, welfare and pharmaceutical services nearby; alcohol and illicit drugs at hand; an unpoliced multi-storey car park in which to consume them; set against a backdrop of an alternative economy of petty crime.

Of course, this manner of living is not conducive to a long and happy existence. The average life expectancy for women in Torbay is 82, and 79 for men. The gap in life expectancy between the most and least deprived parts of the Bay is 8 years; but the average age of death for the street homeless is 45.

Of course, this manner of living is not conducive to a long and happy existence. The average life expectancy for women in Torbay is 82, and 79 for men. The gap in life expectancy between the most and least deprived parts of the Bay is 8 years; but the average age of death for the street homeless is 45.

It was belatedly realised how conspicuous, upsetting, disruptive, and sporadically criminal, these relatively small number of men and women were. Attempts were then made to design the ‘new underclass’ away. Toilets were closed, doorways blocked, benches and phone boxes removed, and low walls made uncomfortable for sitting. Inevitably, this also dissuaded others from using Castle Circus as a place to spend their leisure time.

Every large conurbation now has its Castle Circus, a product of the breakdown of an income distribution system and the subsequent and accelerating polarisation of wealth and poverty. That untidy intersection of Torquay roads has now become a microcosm of poverty in modern Britain, a shadow culture, where the vulnerable, and those that prey upon them, live in the interstices of society.

Every large conurbation now has its Castle Circus, a product of the breakdown of an income distribution system and the subsequent and accelerating polarisation of wealth and poverty. That untidy intersection of Torquay roads has now become a microcosm of poverty in modern Britain, a shadow culture, where the vulnerable, and those that prey upon them, live in the interstices of society.

Some see a disparate group of life’s casualties while others fear the emergence of a new post-industrial cohort of the excluded and impoverished, the return of the Victorian underserving poor. Whatever the reality, the habitants of Castle Circus are just the conspicuous tip of the iceberg of a far greater poverty.

‘Torquay: A Social History’ by local author Kevin Dixon is available for £10 from Artizan Gallery, Lucius Street, Torquay, or:

https://www.art-hub.co.uk/product-page/torquay-a-social-history-by-kevin-dixon