So when did Torbay become Christian?

We know that the first recorded inhabitants of Torbay were a Celtic people who inhabited Dumnonia, which is now known as Devon and Cornwall, along with parts of present-day Dorset and Somerset. The Dumnonii lived in Torbay from at least the Iron Age up to the early Saxon period.

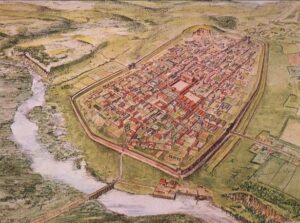

When the Romans established their 42-acre fort in around AD 55, at the southwest terminus of the Fosse Way, this served as the base of the 5,000-man Second Augustan Legion. This civitas would dominate South Devon for 350 years. The Romans referred to this place as Isca Dumnoniorum, ‘Watertown of the Dumnonii’- we know it as Exeter.

The Dumnonii maintained a tradition of independence and Devon was never as Romanised as Somerset and Dorset. Evidence of Roman occupation is limited mainly to the area around Exeter- the newly discovered Ipplepen settlement has challenged old orthodoxies, however.

The assumption is that there were many Dumnonian gods linked with nature and specific places. During the Roman occupation this tradition wasn’t challenged – both the Romans and Britons believed that as well as supreme or general gods, there were also local gods or spirits. Accordingly, the Romans were largely tolerant of other religions, provided that the conquered incorporated the Imperial Cult into their worship.

This is where it’s worth noting that past historians often had a message to push – about when Christianity came to Devon, whether the faith was extinguished after the Romans left, and which was the ‘real’ version. All were fiercely debated over centuries. Early Christian commentators were naturally critical of pagan religions; Catholic historians were promoting the idea that theirs was the faith of both past and present; while Protestants were keen to critique Catholicism as an aberration and to emphasise ‘traditional Celtic’ Christianity.

It’s not clear when Christianity was introduced to Britain, but the faith seems likely to have come came along trade routes from the Mediterranean, Roman artisans and traders spreading the narrative of Jesus alongside stories of their pagan deities – Christianity being just one cult amongst many.

The first evidence showing a British Christian community large enough to maintain churches and bishops dates to the third century. Christianity became increasingly popular after the conversion of the emperor Constantine in AD 312 and by AD 391 Christianity was the official Roman religion. Proclaiming the faith may have been a major factor in defining oneself as being Roman and so at least some of the local elite would become Christian, particularly around the regional capital of Exeter. Whether Christianity was more than the preserve of urban, upper-class Romano-Britons is unclear, however. On the other hand, Britain did not receive as many missionaries as other parts of the Empire and so Torbay’s Iron Age farming settlements of Walls Hill and Berry Head probably continued their ‘pagan’ belief system almost unaffected.

By the beginning of the fifth century Rome was under attack and the imperial dream disintegrating. The Romans then left to defend what remained of their Empire and the kingdom of Dumnonia re-emerged; based on the former Roman civitas and covering Devon, Cornwall and Somerset.

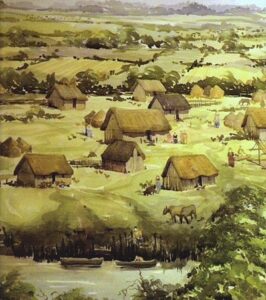

It appears as if the Roman way of life slowly disappeared as Exeter ceased to function as a town and people drifted away to return to a more rural way of life. The degree to how much – if any – Roman culture and Christian practice persisted is debateable.

To support the argument that Christianity did survive in the far South West, we have the mythology of the Christian King Arthur who supposedly repulsed advancing pagan invaders. These were the Anglo-Saxons who were bringing with them a variant of Germanic paganism that had already destroyed most of the formal church structures in the east of Britain as they progressed.

During the fifth and sixth centuries post-Roman Dumnonia was the focus of missionary activity, suggesting that the territory needed such attention. We need, however, to be a little wary of stories about the lives of the saints, ordinary humans who had become extraordinary; and their use of miracles to help their supporters and to spread the faith. These tales are known as hagiographies, had a political motive and treated their subject with reverence. Told in sermons, performed in plays and the focus of prayer and pilgrimage, we know of the lives of almost 300 English saints. These were the celebrities of medieval culture and some were fabricated; such as the legend of a mission by Joseph of Arimathea, though we still have Blake’s, “And did those feet in ancient time”.

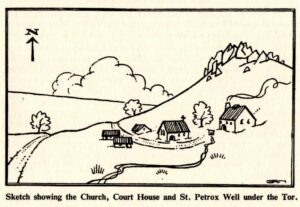

Local evidence is scant, though Preston comes from the Old English ‘preost’ ‘priest’ + tun ‘enclosure’, ‘settlement’; a ‘village with a priest’ or ‘village held by the Church’ which could suggest a missionary station.

Meanwhile, those advancing Germanic-speakers, themselves of diverse origins, eventually developed a common identity as Anglo-Saxons and established kingdoms in the south and east of Britain. Gradually they would conquer the rest of modern England and the far west would eventually fall, but by then the Anglo-Saxons had converted to Christianity.

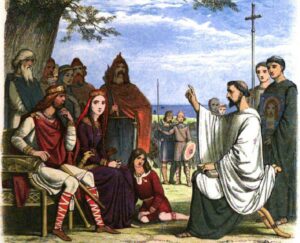

The pagan Anglo-Saxons had attracted missionaries from two directions. The Celtic Church, from their bases in Wales, Cornwall, and Ireland, made inroads in the north from a base on Lindisfarne Island. Meanwhile, the Roman Catholic Church approached from the south, beginning with the mission of St Augustine to Aethelbert, King of Kent, in 597.

The Celtic and Roman churches had differences of opinion and practice; even celebrating Easter on different days. The Celtic church was loosely organised, frugal, fervent, and based on monastic life. In contrast, the Roman tradition was more focussed on structures and discipline. They met at the Synod of Whitby in 664 to resolve their differences, and the Roman cause triumphed.

Roman Catholicism then gradually took over from Celtic Christianity and the Church became an important force in society. It was the only truly national entity tying together the different Anglo-Saxon kingdoms and has been intimately linked with monarchy ever since.

Regional monasteries were established to better serve an area. These were designated minsters and much of the early work of spreading the gospel was done from these large churches; the term lives on locally in Axminster.

Communities constructed churches which were modest wooden structures. Many now lie under the stone built places of worship that replaced them in the eleventh and twelfth centuries – St Marychurch, Paignton and Torre, are examples.

As the kingdom of Wessex expanded westwards, a new diocese was created at Sherborne in 705. This acted as the mother church of Somerset, Devon and Dorset. In 905 Devon was given its own bishopric, possibly at Bishop’s Tawton, though it quickly moved to Crediton. Bishop Leofric eventually transferred his ‘see’ – the bishop’s jurisdiction – to the old Abbey at Exeter in 1050.

Unfortunately, we know very little about the first millennium in Torbay. The Bay was a backwater of little note and only fragments of records survive.

There were also few inhabitants. At the very end of the Anglo-Saxon period we have the Domesday Book, that ‘Great Survey’ of 1086, to give us a good idea of the population. It tells us that 15,500 people lived in Devon, probably representing a total of some 80,000 – less than that of Torquay and Paignton alone at the present day. If we look more closely at the Bay, we see that:

• Brixham was the property of Iudhael of Totnes and had a recorded population of 39 households and 12 slaves.

• Paignton was owned by the Bishop of Exeter. There were 52 villagers, 40 smallholders, 5 other population, and 36 slaves.

• Churston was owned by Iudhael of Totnes, and had 8 villagers, 7 smallholders, 3 cottagers and 7 slaves.

• Cockington was held by William of Falaise, and had 18 villagers; 6 smallholders; and 14 slaves.

• St Marychurch was owned by the Bishop of Exeter with 4 villagers and 4 smallholders; alongside Count Robert of Mortain with 5 villagers, 8 smallholders and 3 slaves.

• Tormoham (now Torre in Torquay) was the property of William the Usher with 16 villagers, 12 smallholders and 4 slaves.

Even though both Brixham and Paignton were in the largest 20% of English settlements, the total population of Torbay was only around 1500 people. The Bay consisted of communities long exposed to both Viking and Saxon seaborne raiding parties. But they were Christian and would remain so until the beginning of the twenty-first century.