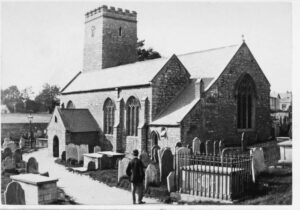

Just off Lucius Street, in the north east corner of the churchyard of the Greek Orthodox Church of St. Andrew, is a mass grave known as ‘Cholera Corner’.

This was a pit, dating from 1849, used to quickly manage the burial of a large number of the victims of the disease.

Cholera pits were used in a time of emergency and responded to public fears of contagion. Many of the victims were poor and lacked the funds for memorial stones, though in other places memorials were sometimes added at a later date. Torquay’s Cholera Corner, however, remains unmarked.

We don’t know much more about the site but bodies were sometimes burnt before internment, or wrapped in cotton or linen and doused in coal-tar or pitch before being placed into a coffin. After being sprinkled with quicklime, the remains were buried in an 8 feet deep pit in the hope of preventing the further spread of the disease.

We don’t know much more about the site but bodies were sometimes burnt before internment, or wrapped in cotton or linen and doused in coal-tar or pitch before being placed into a coffin. After being sprinkled with quicklime, the remains were buried in an 8 feet deep pit in the hope of preventing the further spread of the disease.

Cholera is an illness caused by a germ invading the bowels. The disease is rarely transmitted directly from one person to another and is usually spread by contaminated water supplies.

Cholera is an illness caused by a germ invading the bowels. The disease is rarely transmitted directly from one person to another and is usually spread by contaminated water supplies.

The main symptom is diarrhoea which leads to fluid depletion and death from dehydration. Until the second-half of the nineteenth century, about 50 per cent of the people who caught cholera died as a consequence.

Though cholera had been a killer disease in Asia for over a thousand years, it first came to Torquay in 1832 – the same year it reached London and Paris.

Sometimes sailors came ashore already infected with cholera. Indeed, Devon with its many ports was second only to London in its casualty rate during the epidemic of 1832. Torquay’s later outbreaks have been linked to the railway which brought people from badly-infected areas such as London.

Notably, ‘Torre’ railway station opened on 18 December 1848 and the Torquay station on 2 August 1859.

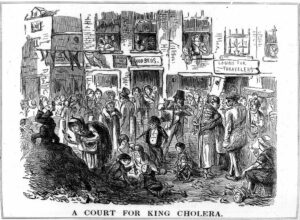

The second major Torquay outbreak happened in the autumn of 1849 when over 33,000 people died of cholera across Britain over a period of three months. As before, the underlying cause was the primitive level of sanitary arrangements in the town.

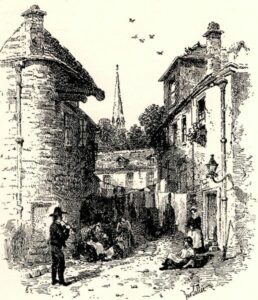

For example, pictured above and below is Pimlico – where the traffic now runs to avoid the pedestrianised Lower Union Street – which had a population of over 200 of the poorest living in overcrowded conditions. They got their drinking water from the River Fleet which ran through the narrow valley. The Fleet also acted to take sewage out to sea via Torquay harbour.

For example, pictured above and below is Pimlico – where the traffic now runs to avoid the pedestrianised Lower Union Street – which had a population of over 200 of the poorest living in overcrowded conditions. They got their drinking water from the River Fleet which ran through the narrow valley. The Fleet also acted to take sewage out to sea via Torquay harbour.

In such a setting disease spread quickly. Sixty-six people died from cholera and dysentery over a period of just six weeks. Many of the dead were buried in Cholera Corner.

In such a setting disease spread quickly. Sixty-six people died from cholera and dysentery over a period of just six weeks. Many of the dead were buried in Cholera Corner.

As was to be expected, the cases occurred mainly in those oldest and poorest parts of town – Pimlico, Swan Street and George Street (which is now buried beneath Fleet Walk). In an effort to contain the outbreak, many inhabitants were removed to wooden houses which were temporarily erected at a cost of over £425 in Plainmoor’s Boston Fields – now built over. Others found refuge in the Torwood Toll House and a cement factory in Union Street.

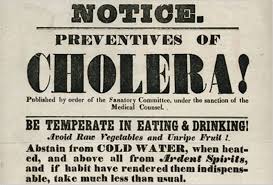

At the time, it was assumed that cholera was airborne. However, in 1854 Dr. John Snow realised that a London infection was coming from a single water pump in Soho. By simply taking away the handle from the pump, he ended the outbreak almost overnight.

Even though Snow’s ‘germ’ theory of disease was not widely accepted until the 1860s, Torquay’s authorities had already begun to take action to tackle overcrowding and disease. During the epidemic £1,176 was raised by the Guardians of the Poor. This was for Parish Relief for 882 poor persons, medical aid and the improvement of sanitary conditions.

Even though Snow’s ‘germ’ theory of disease was not widely accepted until the 1860s, Torquay’s authorities had already begun to take action to tackle overcrowding and disease. During the epidemic £1,176 was raised by the Guardians of the Poor. This was for Parish Relief for 882 poor persons, medical aid and the improvement of sanitary conditions.

Torquay adopted the Public Health Act and the first meeting of the Local Board of Health took place in September 1850. Conditions then gradually began to improve.

Torquay adopted the Public Health Act and the first meeting of the Local Board of Health took place in September 1850. Conditions then gradually began to improve.

In 1865 the Local Board of Health made “a good wide street between the bottom of Union Street and the Strand.” This replaced the narrow and cramped alleyways on both sides of the River Fleet. At the same time, the Fleet was confined to a tunnel.

Today, the Fleet remains underground and the broad highway still runs through Torquay from the Strand to Castle Circus – you can still hear the Fleet rushing below you if you stand outside Primark.

Today, the Fleet remains underground and the broad highway still runs through Torquay from the Strand to Castle Circus – you can still hear the Fleet rushing below you if you stand outside Primark.

The last serious European cholera outbreak took place in Germany in the 1890s. Since then modern sanitation and the treatment of drinking water have virtually eliminated the disease in developed countries. In third world countries, however, cholera remains common.

‘Torquay: A Social History’ by local author Kevin Dixon is available for £10 from Artizan Gallery, Lucius Street, Torquay, or:

https://www.art-hub.co.uk/product-page/torquay-a-social-history-by-kevin-dixon