“Some were in the sea, some were lying stretched out in the sun, and some were anointing themselves carefully with oil”, Agatha Christie’s ‘Evil Under the Sun’ (1941)

It was during the 1920s that people in Torquay started taking their clothes off. They had decided that they wanted to change the colour of their bodies.

In less than a decade the resort experienced a social revolution that replaced Victorian conservatism with the pursuit of pleasure. Smoking, drinking, partying, and the display of bronzed legs and shoulders, proclaimed new freedoms.

Underlying trends were already discernible at the turn of the century, and late Victorian Torquay was a liminal place open to outside influences and always in the front-line of change. But this was an acceleration of history indisputably caused by the shock of the Great War.

Seaside resorts were a British invention, a form of leisure community and a way of living that could be visited by those who had the means to do so. 1720s Scarborough was probably one of the first to offer an alternative to the fashionable spa towns.  The seaside leisure town concept then spread to 27 major British resorts and soon equivalents appeared on the northern European coastline. By the early nineteenth century sea-bathing was to be seen in south-west France, Germany and Scandinavia. Soon the practice reached Spain and then the French and Italian Rivieras. Eventually the seaside resort would become an essential component of a global tourism industry.

The seaside leisure town concept then spread to 27 major British resorts and soon equivalents appeared on the northern European coastline. By the early nineteenth century sea-bathing was to be seen in south-west France, Germany and Scandinavia. Soon the practice reached Spain and then the French and Italian Rivieras. Eventually the seaside resort would become an essential component of a global tourism industry.

The European nations not only eagerly adopted the seaside resort, but created their own characteristics in beach management, architecture and etiquette beyond their British origins. Over the following centuries they then returned the idea to us in an altered, and sometimes improved, form. There’s possibly a parallel here with football.

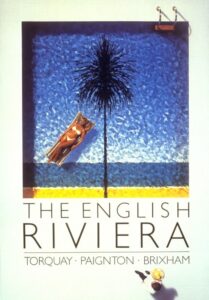

This foreign influence caused a problem for Torquay as our European counterparts adopted more liberal attitudes to casino gambling, drinking, dancing, and relations between the sexes. This contrasted with British aspirations towards dignity and restraint across all social classes, standards maintained through religion, the industrial work ethic, and personal improvement. We wanted, of course, to be just like the Rivieras and attract a sophisticated clientele, but we didn’t want to succumb to ‘continental influences’. Looser standards of behaviour may have been acceptable in Paignton, but not Britain’s premier resort.

We wanted, of course, to be just like the Rivieras and attract a sophisticated clientele, but we didn’t want to succumb to ‘continental influences’. Looser standards of behaviour may have been acceptable in Paignton, but not Britain’s premier resort.

Sea bathing was a particular issue. Foreigners just had other notions of modesty and the intermingling of genders.

Then there was the issue of exposure to the sun. For over a thousand years, pallor was popular with the upper classes; fair skin let others know that you could afford an indoor life of leisure while darker skin was associated with serfdom and toiling in the fields. When, for instance, Elizabeth Bennett, the heroine of Jane Austen’s ‘Pride and Prejudice’, acquired a mild tan after a country walk, she caused a bit of a scandal.

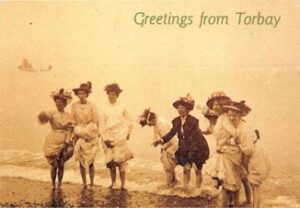

Most women did not actually swim. If they did, bathing machines were provided. The object of visiting the coast was the promenade and it was expected that Victorian women would shield themselves with parasols, hats and gloves.

Within a few years beachwear would change dramatically

In 1897 Annie Cann was in Torquay and recorded in her diary, “We walked along the promenade. We found it very clean, very white, very fashionable, and very hot. White walks, white dresses, blazing sun, no breeze, and no shade. Everyone wore gloves and carries a parasol… It is a place of ease, luxury, riches, convenience and prettiness – it cannot be called beautiful – for it is too artificial and unromantic to stir a pulse.”

Accordingly, people went to the beach despite the sun and Torquay was best avoided in the hottest months of the year.

There are complex relationships here between skin colour, race, class, gender, and sex and existential questions around the maintenance of hierarchies and the imperatives of order. Indeed, Torquay was at the very epicentre of the British Empire at leisure and espoused the belief that exposure to the sun could erode moral fibre. One only had to look at the fate of the sun-blasted fallen empires of the Greeks and Romans.

By the later nineteenth century, however, attitudes were changing. Urbanisation caused the working class to take their leisure indoors and many were employed in mines and factories. Pale skin subsequently became associated with the lower classes.

At the same time, it was becoming known that the sun was actually good for you. In 1890 Theobald Palm recognised that sunlight was crucial for bone development while Niels Finsen was awarded the 1903 Nobel Prize for medicine for his ‘light therapy’ which aimed to combat diseases such as rickets and tuberculosis.

So, while the practice remained to cover up and reveal little, bathing was accepted as improving the quality of life. Tanned skin then began to suggest that you had the time and money to darken your complexion.

Coco Chanel, “I think she may have invented sunbathing.”

The apocryphal shift came in 1923 when, after mistakenly catching the sun, iconic French designer Coco Chanel displayed bronzed skin. Her friend, Prince Jean-Louis de Faucigny-Lucigne, pronounced, “I think she may have invented sunbathing.”

French beachside resorts then started to remain open throughout the summer, their usual off-season, which led to sunbathing as a pastime for the rich and stylish. Within a few years the character of the Riviera had changed to become a year-round destination, encouraging others, including Torquay, to adopt the same marketing strategy.

Magazines featured suntanned women and promoted the idea of underdessing rather than overdressing. In 1928 Jean Patou introduced the first tanning oil; and in 1929 Vogue declared that the “sunburn movement” had created a whole new tanning industry. Women’s bathing suits reduced in coverage and in 1946 separated to become bikinis. Torquay, always eager to replicate the glamour of the Rivieras, embraced the new activity and by the mid-1920s sunbathing had become a local health craze. Continental styles and attitudes then reshaped the town’s architecture, with balconies, sun terraces, and flat roofs, all facilitating sunbathing.

Torquay, always eager to replicate the glamour of the Rivieras, embraced the new activity and by the mid-1920s sunbathing had become a local health craze. Continental styles and attitudes then reshaped the town’s architecture, with balconies, sun terraces, and flat roofs, all facilitating sunbathing.

Aided by affluence and paid annual leave, the British seaside holiday really came into its heyday in the 1950s and 60s. A suntan could prove you had truly holidayed when you returned to the factory or office.

Sea bathing and the suntan reshaped and reinvigorated Torquay. In time though, the export of the resort model would return with a vengeance to present our tourism industry with its greatest challenge. From the 1960s there came more attractive overseas holidays, while colour film allowed the holidaymaker to come home with hard evidence of their sun-drenched vacation.

Will the tourists ever come back to Torquay?

Our overseas Empire-builders knew of the harmful effects of the sun, but this awareness didn’t appear to reach most twentieth-century beachgoers. Only later came an understanding that overexposure can lead to one of the commonest forms of cancer. Today, skin cancer is significantly more common in Torbay than the nation’s average and incidences are rising.

So, do visit the beach, but be careful. One good reason why Torquay is developing cultural alternatives to sun-worshipping and striving to create new or, in some places, traditional identities.

Meanwhile, Mediterranean coastal destinations are experiencing climate change and becoming less habitable. Spain’s health ministry recently said there was a “real risk” to the nation’s mass tourism due to rising temperatures, fires, and more frequent heat waves. Tourism, he warned, could disappear “from parts of his country.”

Admittedly, it’s hotter and sunnier in the Mediterranean, which is why we go there. But it seems that it may well get too hot and too sunny in the future.

And so, the great British seaside resort experience, sent overseas and repackaged, may once again be coming home.

Torquay: A Social History by local author Kevin Dixon is available for £10 from Artizan Gallery, Fleet Street, Torquay, or:

https://www.art-hub.co.uk/product-page/torquay-a-social-history-by-kevin-dixon