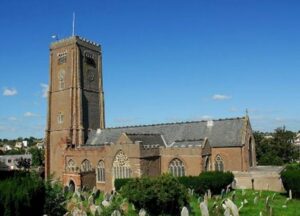

Across Torbay our ancient medieval churches have strange grooves carved into their outside walls.

In 1932 the historian Waterfield, while describing St Mary the Virgin in Brixham Brixham, suggested that these grooves had been made by the sharpening of arrows.

In Paignton we even have an old postcard which states ‘Marks due to arrow sharpening, Parish Church, Paignton’.

In Torquay the original St Saviours has similar marks which have long been identified as being caused by arrow-sharpening.

These shallow grooves cut into the stones have long been supposed to be the consequence of mediaeval archers honing their arrows during practice sessions. The idea is that the steel tip of an arrow would be drawn up and down the stonework to create a sharp edge before heading off to practice in the churchyard.

Often, throughout England and Wales, the practice is linked to victories in France in the Hundred Years War; such as Crecy in 1346 or Agincourt in 1415, where a force including 6,000 archers triumphed over an overwhelming French army. The English relied on the power of massed ranks of archer’s shooting war bows which could launch at least six arrows per minute. To provide such a force, boys would train from as early as 6 years of age and men aged between 15 and 60 could be conscripted.

And so, the legend goes, former members of Torbay’s villages participated in famous military victories and helped to build an England that would become the greatest empire the world had ever known.

So, are the grooves evidence of arrow-sharpening?

First of all, there is no documentary evidence to support the claim that archers sharpened their arrows on the stones of church porches.

Archers would be unlikely to practice in churchyards. Churchyards were consecrated ground and various prohibitions were enforced against the practice. The majority of churchyards were also just too small for archery. Henry VIII legislated that archers over the age of 24 must not shoot from less than 220 yards from the target. What evidence we do have indicates that archery butts were located elsewhere in the manor.

Indeed, there was really no need to scrape the arrowheads on the walls of a church or anywhere else as practice arrows did not need to be sharpened. An archer’s equipment included portable whetstones and files for sharpening broadhead arrows. Broadheads would have damaged any butts, and bodkins were designed to detach on impact, so archers practiced with round-headed arrows that didn’t need sharpening.

Trying to hone a sharp edge against Torbay sandstone would also have just blunted any edge. Further, many of the grooves are orientated vertically and are low to the ground which makes them impractical for drawing a metre long arrow shaft across the stone.

So what were these grooves?

We don’t have a specific answer. But all churches and shrines were considered to have special powers due to their ritual consecration.

And we do have folk traditions from across Europe that refer to parishioners scraping powder from church stonework. The dust was then mixed with holy water or wine and consumed as a potion to cure fevers, cancer, dysentery and various infirmities; or incorporated in mineral poultices which were applied in attempted injuries.

It may be that our churches were Torbay’s first self-serve pharmacies…