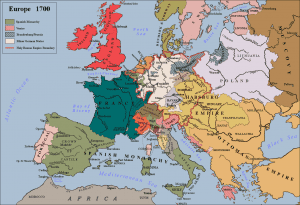

The English have fought so many wars – many now forgotten as are the men and women who died as a consequence. One of these conflicts was the Nine Years’ War (1688–97). This was a major struggle fought between King Louis XIV of France, and a European-wide coalition called the Grand Alliance. We were part of the Alliance which was led by the Anglo-Dutch William III, the Holy Roman Emperor, a variety of princes of the Holy Roman Empire and the King of Spain.

It was fought primarily on mainland Europe and its surrounding waters. However, it also encompassed fighting in Ireland, Scotland and a campaign between French and English settlers and their Indian allies in colonial North America.

The main fighting took place around France’s borders in campaigns dominated by siege operations. Yet, by 1696 France was in the grip of an economic crisis and the Maritime Powers (England and the Dutch Republic) were also financially exhausted. Peace, though short-lived, was finally declared in 1697.

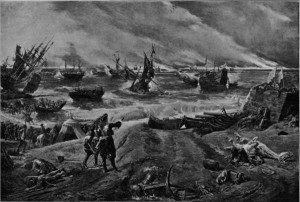

A number of naval engagements took place with the English navy being involved in a number of successful actions. For example, at La Hogue in 1692 an English fleet destroyed 12 French ships of the line and a number of smaller ships with minimal English casualties (pictured below).

It may have been expected that England would have been deeply grateful to its sailors. This wasn’t to be. On June 24 1696, the Lords of the Treasury received a representation from the Commissioners regarding sick and wounded seamen stating that, “At Plymouth there were about 300 seamen and 500 prisoners, and the agent wrote that they must starve for he had not 5 shillings to subsist them, and desired to be discharged from the service if he could not be supplied; that there were from the grand fleet above 700 sick seamen at Torbay, and the people not able to provide for them”.

The Commissioners concluded, “We have no money to send the recovered seamen to their ships.”

The English generals having been able to feed their men in Flanders were now finding it impossible to prevent the men from starving on the shores of Torbay. Yet, England wasn’t bankrupt. The nation just didn’t have any ready cash.

In 1696 William III had ordered the old hammered coinage to be withdrawn. So much of it had been clipped down by people wanting the silver to sell as higher-priced bullion. This meant the coins were of varying shapes and sizes, making nonsense of their face value. The coins were supposed all to be worth the same but in practice each had a different amount of silver in it.

To replace the withdrawn coinage, during 1696 a vast quantity of new coins was produced, with some coming from mints at Exeter (see image above). Yet, it took time to produce the new coins and much of it promptly disappeared into hoards or was sent abroad. Some was also melted down because silver bullion was still worth more than coins of the same weight.

In his Diary of 11 June 1696 John Evelyn wrote of the shortage of coins, “Want of current money to carry on not onely the smallest concernes, but for daily provisions in the Common Markets; Ginnys (Guineas) lowered to 22s: & greate sums daily transported into Holland, where it yields more, which with other Treasure sent thither to pay the Armies, nothing considerable coined of the new & now onely current stamp, breeding such a scarsity, that tumults are every day feared.”

Meanwhile, due to the lack of coins, in Torbay 700 sailors starved…