During the course of the nineteenth century Torquay grew to become the richest town in Britain. Many millionaires lived or visited, though amidst this wealth and sophistication, folk who were unable to provide for themselves could find a cruel home in Newton Abbot’s Workhouse.

It was the 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act that established workhouses.

Before that date, the aged, sick and destitute relied on handouts from the wealthy and the church, or they received outdoor relief in the form of money, clothing, food, fuel and medical care.

However, there were growing concerns about rising levels of poverty and the increasing pressure on local poor relief.

In response, the new Act altered the system from this locally organised support to a centralised system which banned outdoor relief. All 15,000 parishes in England and Wales were then instructed to form Poor Law Unions. Each was to have its own workhouse, supervised by a local Board of Guardians.  Hundreds of new workhouses were subsequently erected across the country.

Hundreds of new workhouses were subsequently erected across the country.

During the 1830s Torquay had a population of around 5,000 and so only needed a small workhouse. This stood on the site of what is now 8 Church Street in Torre.

Yet the Bay’s communities were rapidly growing. A decade after the railway’s arrival in 1848 the population stood at almost 15,000. New arrangements clearly had to be made, and this came on 20 June 1836 with the setting up the Newton Abbot Poor Law Union.

While most Poor Law Unions covered around 12 to 18 parishes, the Newton Abbot Union had a membership of 36 parishes surrounding the town. Those parishes included Cockington, St Marychurch, and Tormoham (Torre).

“The tempers become deranged.” Newton Abbot’s Workhouse

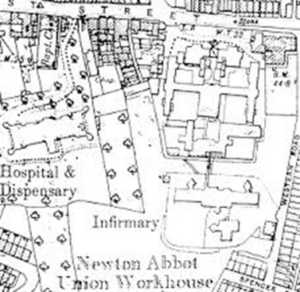

In 1837 the Newton Abbot Union completed its workhouse in East Street. The site is around where the Sainsbury’s Local Store is now.

Admission to the 350 inmates was supposed to be voluntary but from its inception the workhouse was made deliberately unwelcoming and harsh.

It needed to be as conditions were often so awful in Devon’s towns and villages with disease and starvation commonplace. Workhouses had to be seen as a last resort and consequently even the starving and dying avoided them.

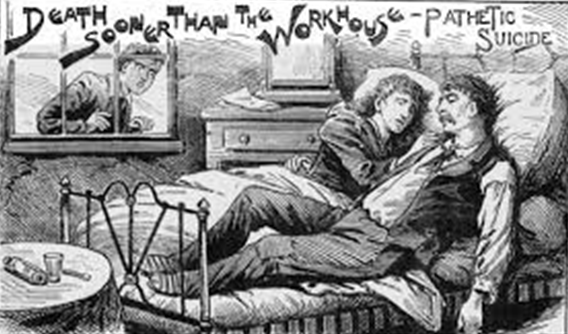

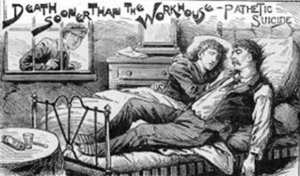

Sometimes death was preferable to the workhouse

Indeed, shame was part of the deterrent. Suicides, both outside the workhouse and within its walls, were common. In 1847, for instance, an elderly man took his own life by throwing himself out of a window.

The desperately poor of all ages, the mentally ill, and disabled were, for decades, then transported out of Torquay to a place where they would not offend tourist sensibilities.

As a visible deterrent, workhouses were often built on higher ground to be seen by all, as was the case in Newton Abbot. Isolated behind high walls, the buildings were designed to provide segregated accommodation for the different categories of pauper; male and female, boys and girls, able bodied and infirm.

New inmates would be given a uniform and discouraged from talking to one another. This objective wasn’t always achieved. In 1853, for example, two inmates became pregnant.

As the name suggests inmates were expected to work long hours undertaking manual labour. Food was poor. In 1853 bread was described as “like putty” and not fit for human consumption.

In desperation, a mother leaves her child to the care of others, by Henry Nelson O’Neil (1855)

Particularly stigmatised in a patriarchal society were unmarried mothers and their children.

A ‘bastardy clause’ in the 1834 Act made all illegitimate children the sole responsibility of their mothers until they were 16 years old, leaving the father free of any legal responsibility. As unmarried pregnant women were often disowned by their families, this often made the workhouse the only resort during and after the birth.

This measure was overturned in 1844, allowing an unmarried mother to claim against the father for maintenance. This was, of course, if the father could be located and paternity proved. Hence, unmarried mothers from poor backgrounds still entered the workhouse to have their babies.

The alternatives to placing infants in workhouses, where their survival was uncertain, were few. One was infanticide. In 1849 a baby’s body was found in what was to become Torquay’s Warren Road; and in 1858 a tiny corpse was found floating off Anstey’s Cove.

Another option was to turn to baby farmers who provided childcare but who also were known to murder unwanted infants. In 1865 Charlotte Winsor was arrested at her small cottage near Torquay’s Lowe’s Bridge. This followed the discovery of the body of Mary Jane Harris’ illegitimate four-month-old son beside a road near Torre Station.

An indication of just how much in contempt unmarried mothers were held, and the supposed danger they were to society, came in 1850 when Newton Abbot’s Workhouse found it necessary to cut its costs. Inmates would then be expected to work 6 hours a day. However, the mothers of “bastards” were told to work 8 hours a day as they were “vicious and depraved women” needing to be kept away from the others. Across the nation abuse was common, though times were changing, and notice was beginning to be taken.

Across the nation abuse was common, though times were changing, and notice was beginning to be taken.

In 1894 there was an investigation into practices at Newton Abbot’s Workhouse.

Witnesses described that the wards were filthy, and infested with vermin. Food was kept in the lavatories.

It was found that a straitjacket, called a ‘jumper’ was being used, and that elderly paupers had been placed in it naked, and then tied to beds. This had led, it was alleged, to the deaths of some inmates. Another witness said she saw two men tied to the same bed.

A nurse testified that she had found a female inmate dying, her hair had been cut off, and her toenails were like claws. A paralysed inmate had injured herself with her uncut fingernails.

Another nurse said she had been given sole charge of 150 ill paupers. Sick children were under the care of two partially blind women. One child had been tied to a bed with string to prevent it from running about as it had no shoes and stockings. Eleven children had four nightgowns between them.

A woman with, what we would now call, learning disabilities was observed in the workhouse yard crouched in a corner with a bruised face. A shed had been built for her in the yard but boys, including the master’s son, threw stones and snowballs at her. Fighting amongst the inmates, who were described as “idiots”, was commonplace.

What seems to have been particularly shocking to the devoutly Christian inspectors was the “immorality” of those confined.

The matron for almost thirty years, Ann Mance, was accused of neglecting her duties, dismissed, and died from a heart condition a few weeks later.

Nevertheless, the workhouse remained in use for decades. By the time of a Torquay Times visit in 1928, it was now called the Newton Abbot Union Institution. The term workhouse had by then become tainted.

By the time of a Torquay Times visit in 1928, it was now called the Newton Abbot Union Institution. The term workhouse had by then become tainted.

The newspaper’s correspondents reflected society’s view that the very poor should be punished as well as supported: “The pauper suffers in a general sense for the improvidence of which he has been guilty, exactly as a criminal expiates his wrongdoing behind bars.”

These men and women had their freedom tightly restricted: “What hurts the bulk of the inmates is the confinement. There are some inmates who very rarely, if ever, go outside the walls… With some of them melancholia is engendered and eventually become anything but normal. The tempers become deranged.”

In effect, if you didn’t have a mental illness before you entered the workhouse, you would soon acquire one. Workhouses were only officially abolished by the Local Government Act of 1929, but many persisted into the 1940s. Workhouse buildings, such as the one in Newton Abbot, were then widely re-used in the National Health Service.

Workhouses were only officially abolished by the Local Government Act of 1929, but many persisted into the 1940s. Workhouse buildings, such as the one in Newton Abbot, were then widely re-used in the National Health Service.

Torquay: A Social History by local author Kevin Dixon is available for £10 from Artizan Gallery, Fleet Street, Torquay, or:

https://www.art-hub.co.uk/product-page/torquay-a-social-history-by-kevin-dixon