Vane Tower on the skyline above the harbourside

In a ten-minute drive around Torquay, you can pass nineteenth and twentieth century buildings that encompass a mosaic of architectural trends from Europe’s past. They illustrate an evolution in how our ancestors envisioned their world.

Local architects and their sponsors have always borrowed freely from a range of old and new styles. They then used them in novel and overlapping combinations in our homes, hotels and public buildings.

Specifically, we wanted to give the message to both visitors and residents that here was a new kind of place, a resort located somewhere in a sunnier Europe, albeit without the Babel of languages, the unfamiliar food, or surly locals. Certainly, there would be no discourteous policemen demanding, “Papiere, bitte”.

That was the whole point of Torquay. A combination of an idealised England and a romanticised continent.

In 1800 an embryonic Torquay only had a population of around 800. This gave incomers and visionaries an almost blank canvas on which to work in order to attract a sophisticated and, above all, affluent clientele.

And what architectural style could be more appropriate than one that replicated the buildings and gardens of the Mediterranean.

Torquay’s Italianate Old Town Hall

This was the Italianate, most popular between 1840 and 1885, a phase in the history of Classical architecture, a backward gaze that evoked Florence and the Italian countryside. Torquay then created a three-dimensional postcard of those European tours so favoured by Britain’s elite.

The Italianate style was initially intended as a suitable design for substantial country homes and so was first introduced in two or three acre sites on the southern slopes of the Warberries and the Lincombes.

The earliest examples of the Italianate in the resort are ‘Vomero’ in Stitchill Road, built in 1838, and ‘Wellswood Hall’ constructed a few years later.

Many more followed, 500 ‘villas’ according to the claim, reflecting the image the English had of an Italian villa with its low pitched roof and overhanging eaves. One of the most notable features was the campanile, imitations of the square church bell towers seen in Italy. Hence, we have Vane Tower on the skyline above the harbourside; while Lower Union Street/Abbey Road has the clock tower of the Old Town Hall of 1852.

La Scala, Milan’s eighteenth-century opera house

Torquay’s Scala, built in 1909 but never used for its intended purpose

Italian imitations were always part of our English Riviera. Torquay’s Scala began in 1909 and was modelled on La Scala, Milan’s eighteenth-century opera house, where many of the finest singers from around the world performed. As the richest town in Britain, we deserved an opera house of our own to attract the right type of visitor. Then the Great War changed everything, and the Scala never fulfilled its purpose.

The style was easily adapted and could encompass spacious homes on sprawling properties for Torquay’s wealthy, while also fitting into much smaller urban plots. Its flexible floor plans were particularly suitable for hotels which could be altered without being demolished and rebuilt. The Imperial Hotel is a good example. Built in 1866 the original Italianate design was enlarged when the Jubilee Wing was added in the 1870s.

The Venetian-style Torquay Museum

Another feature of the Italianate that so suited Torquay was the garden. Often needing to be accommodated on steep slopes, designs featured terraces, flights of steps, statuary, ponds and balustrades adorned with urns. The resort had the further advantage in being able to grow exotic plants to further accentuate that Mediterranean ambience.

An even closer neighbour also provided concepts that helped fashion our townscape. The end of the Napoleonic wars in 1815 led to a rush to cross the Channel and revitalised interest in French design. In consequence, many of our grand private and public buildings have French Chateaux and Renaissance elements, such as gabled dormers, high roofs, chimneys and turrets. A later inspiration came from the ornate Second Empire style which flourished during the 1852–1870 reign of Louis-Napoleon III. Fittingly, in 1871 the recently deposed Emperor stayed at the Imperial Hotel.

A particularly useful import was the Mansard roof. In France, homeowners were taxed by the number of floors in their houses but the Mansard roof could turn tax-free attic space into an extra floor, its dormer windows letting in an abundance of light. This imported novelty was utilised to convert private houses into hotels and guest houses giving Torquay a distinct continental feel.

The French chateaux-style Grand Hotel

As an example, we have the Grand Hotel. In response to the Great Western Railways’ expansion into the South West, the Grand first opened in 1881. Originally with just 12 bedrooms, it was later crowned with a Mansard roof.

Adjacent to the Grand is the railway station. A station serving Torquay had been opened in 1848 but was some distance from the centre of town. A new station near Abbey Sands was then opened in 1859. In 1878 the station was improved to offer a more sophisticated welcome to passengers, the design suggesting a miniature French chateau.

Such Gallic frivolity was tailor-made for seaside resorts looking to attract tourists. Our occasion to really impress came in 1911 in the innovative and visually attractive Pavilion. Built on a concrete raft on reclaimed land, on which a steel framework was erected, the Pavilion was faced with white tiles and featured a copper-covered dome topped with a life-size figure of Britannia.

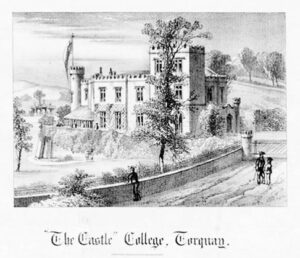

Torquay Gothic, The Castle which gave its name to Castle Circus

The tradition of recreating past building forms also gives us the peculiarly English Gothic Revival. Beginning in the late 1840s, the inspiration was the picturesque and romantic pre-industrial rural landscape. As Torquay marketed itself as being somewhere to escape the hustle and bustle of the nation’s great cities, it was a fitting architecture.

One advantage of the Gothic was that it could be adopted by all classes. It, for instance, inspired Furze Hill’s great crenellated (battlement-like) Gothic ‘Castle’ which gave Castle Circus its name. At the same time, it could mean little more than pointed window frames and mock medieval decorations on terraced houses. Note the Gothic windows in Belgrave Road and the dragon finials on the rooftops of Union Street.

The Gothic Revival was more than mere fashion, however. It was a look back in envy, a reaction to industrialisation, the filth and poverty it brought, and even to change itself.

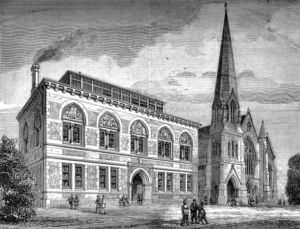

Constructing a middle class: Torre Conservative Club, originally a Constitutional Club

By the 1870s the Gothic had become associated with conservatism and synonymous with inherited authority, hierarchy, individualism, and commerce. A good illustration of this is the old Torre Conservative Club. Originally a Constitutional Club, such institutions were founded in the 1880s in anticipation of the electoral reform that was being debated in Parliament. The Club was a crucial part of the formation of the identity of Torquay’s business-minded middle-class male.

The pointed arches, gothic detailing, sash windows and the black-painted oriels are all original. The Club was meant to impress and would have stood out amongst the surrounding two-storey terraces.

Preston’s Tudor-style house, built as a Lloyds bank in 1924

To see a late flourish of the Gothic we need to travel into Preston. 306 Torquay Road may give the appearance of being a Tudor house but was built as a bank for Lloyds in 1924. The idea was to invoke reliability and stability in a fast-changing world.

The Queen’s Hotel: “Torquay’s contribution to the Jazz Age aesthetic”

Notwithstanding such outliers, the influence of all forms of Revivalism had peaked by the 1870s and new architectural movements were gaining ground. Utilising advances in building materials, Modernism rejected ornamentation or decoration and promoted the use of simple design elements. One example is the 1937 Queen’s Hotel on the harbourside, described as “Torquay’s contribution to the Jazz Age aesthetic”.

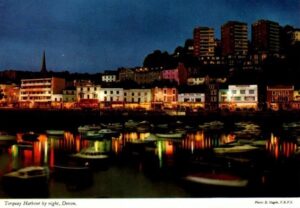

Torquay’s 1960s apartment blocks, once promoted as being so very French

Torquay continues to pillage the world and the romantic past for architectural inspiration. Though today, decorated with eclectic flourishes provided by the Bay’s garden centres, the Spanish hacienda, the colonial bungalow and the Côte d’Azur apartment block, are perhaps more de rigueur.

But whatever the evolutions in style, the message always remains the same, “You’re not in boring old England anymore”.

Torquay: A Social History’ by local author Kevin Dixon is available for £10 from Artizan Gallery, Fleet Street, Torquay, or:

https://www.art-hub.co.uk/product-page/torquay-a-social-history-by-kevin-dixon