As we see daily on Spotted, a lot of us have a great fondness for animals. This wasn’t always so and it took many years to improve how we treat our furred and feathered friends.

As was so often the case, it was in Torquay that a national social change was first embraced. The town was the richest in England and we were often more open to new ideas.

In 1911 the Council of Justice to Animals was formed by a small group of people who were concerned about the methods being used to slaughter animals for food and the ways that cats and dogs were being destroyed. They also wanted to improve the welfare of animals by introducing reforms to livestock markets and transport facilities. Initially, the society set up a number of dispensaries for the animals of the poor and they established branches around the country.

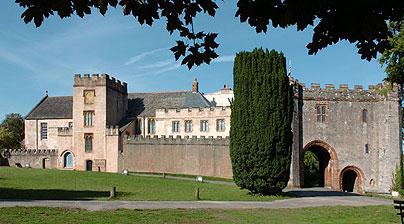

One of these was in Torquay. The inaugural meeting, titled ‘Justice for Animals’, was held in early 1912. Significantly, this meeting was attended by those at the centre of Torquay society, and was held at Torre Abbey by invitation of Colonel and Mrs Cary.

This was a “large and representative gathering” presided over by Admiral Sir William Acland (pictured above) who stated that he was “extremely fond of animals and tried at all times to show them every kindness”. He thought they “deserved to be treated well and he was sure they would be if it was realised how acutely they felt pain and suffering”.

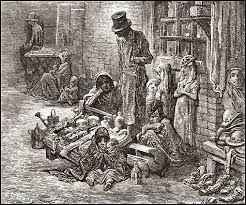

The main speech was by Dr Reinhardt of London, the chairman of the Council of Justice to Animals, who said he was there to, “challenge the right of humanity to make use of the lower animals or to eat animal flesh. Animals were akin to human beings in that they had a capacity for feeling pain, they had all the machinery and all the nerves and all the capacity for experiencing suffering that were possessed by the human being. There was still in very many parts of the country a callous disregard of this important fact.”

“It was a century ago that Darwin had shocked man by making the discovery that the descent of man was not entirely unattached from an animal that travelled by other means than on its two legs. But since then an even greater discovery had been made – that the lower animals were able to feel an intensity of suffering to as great an extent as it seemed possible to get. They could see for themselves examples of the devotion, love, even unselfishness, which many animals possessed.”

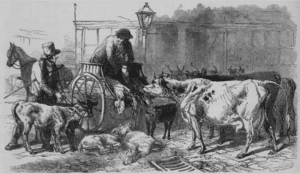

A local branch of the CJA was then set up. It dedicated itself to, “the abolition of private slaughterhouses which were not open to public inspection and where many cruelties were practiced. The workers were frequently inexpert, made use of unsuitable instruments and often showed callous disregard for the suffering of the animals. Dwelling houses existed side-by-side with slaughterhouses. The slaughter was in public view and used by children as public entertainment.”

The CJA’s first aim was to replace the traditional method of slaughter, the pole-axe, with a mechanically operated humane stunner. Demonstrations were to be given to slaughter men and humane stunners were to be supplied to local tradesmen at low prices. As an indication of the meeting’s political influence, the President of the Torquay Master Butchers Association was in attendance and gave his support for the introduction of this, more humane, method of slaughter.

To progress the adoption of the stun gun the CJA advocated, what we would know today as, a consumer boycott whereby the public would be encouraged to only buy meat from animals that had been humanely killed.

Yet, Dr Reinhardt’s interests went beyond humane slaughter, and further than traditional Edwardian compassionate campaigning to an almost animal rights agenda. To a receptive audience he mocked the rationale, still heard today, of those who were involved with hunting and fishing: “They had all heard the story of how the fox enjoyed the hunt as much as the hounds and how the fish delighted to dangle on the end of the hook.”

In 1928 the CJA amalgamated with the Humane Slaughter Association. They continue to work for the humane treatment of the 3 million cattle, 13 million pigs, 19 million sheep and lambs, 70 million fish and 800 million birds which are slaughtered for human consumption each year in the UK.