In 1867 the vicar of St Saviour’s Church in Torre had a drinking fountain constructed just outside his churchyard. He called it Efride’s Well. The inscription read:

“Erected AD 1867 by the Rev John James Vicar and incumbent of this parish. Let him that is athirst come.”

The fountainhead is still there, though the inscription has been mostly lost and the water supply is no more.

While mostly forgotten, this was a crucial water source for the small community that would grow to maturity beneath a craggy tor to eventually become Torquay, the richest town in all England.

Our first record of the spring comes in 1196 when six Premonstratensian canons from the Welbeck Abbey in Nottinghamshire founded Torre Abbey. William Brewer, lord of the manor of Torre, gave them the land up to a boundary line by the ‘spring’.

Our first record of the spring comes in 1196 when six Premonstratensian canons from the Welbeck Abbey in Nottinghamshire founded Torre Abbey. William Brewer, lord of the manor of Torre, gave them the land up to a boundary line by the ‘spring’.

William donated “all the water which comes from the spring of St Petrox near the kitchen of the court-house of Torre”. The grant further said that, though the ensuing stream flowed through the lord’s garden, the canons could enter his property to repair the watercourse. The stream then ran near what became Sands Lane, which we now know as Belgrave Road, onward to the sea.

The manor of Torre became known as Tor Brewer when held by William who died in 1226. His daughter, Alice, married Reginald de Mohun (1185–1213) of Dunster Castle and so we get Tormohun.

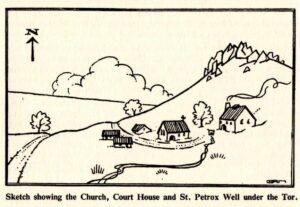

A fair reconstruction of the village of Torre, its principal buildings and Efrideswelle can be seen in Percy Russell’s ‘A History of Torquay’ (1960) (pictured above).

A fair reconstruction of the village of Torre, its principal buildings and Efrideswelle can be seen in Percy Russell’s ‘A History of Torquay’ (1960) (pictured above).

What we do know is that the church by the spring wasn’t always known by the name of St Savour’s. We know this as William’s grant stated that his new Abbey should be built on the place where St Saviour’s was founded. And so it was, indicating that Torre had two sacred sites for a population of around 200 by the time of Domesday in 1086. The first St Saviour’s lies buried beneath Torre Abbey.

Further evidence of the original designation of the church comes from the demise of John Bartlett in 1485. In his will he states:

“I, John Bartlett, leave my soul to Almighty God and my body to be buried in the church or cemetery of Saint Petroc of Torremone”. John’s gravestone is the oldest we have and is in St Saviours.

It seems, therefore, that St Petrox was renamed as St Saviour’s hundreds of years after the establishment of Torre Abbey.

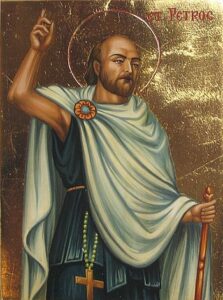

St Petrox, Petroc or Petrock (pictured above), lived between c 468 and c 564 and ministered to the Celtic Dumnonian Britons of Devon and Cornwall. In Devon there are a likely seventeen churches dedicated to the missionary. These are mostly coastal churches, as in Dartmouth; though one is situated within Exeter’s old Roman walls. This has been taken to indicate that Torre’s church was originally a, likely wooden, St Petrox chapel or church and so dates back to the late sixth century.

St Petrox, Petroc or Petrock (pictured above), lived between c 468 and c 564 and ministered to the Celtic Dumnonian Britons of Devon and Cornwall. In Devon there are a likely seventeen churches dedicated to the missionary. These are mostly coastal churches, as in Dartmouth; though one is situated within Exeter’s old Roman walls. This has been taken to indicate that Torre’s church was originally a, likely wooden, St Petrox chapel or church and so dates back to the late sixth century.

The church we know now has, of course, been rebuilt and remodelled over the centuries. Today it is the Greek Orthodox Church of St Andrew. It was constructed in its present form in the fourteenth century on the site of an earlier Norman chapel, greatly renovated in 1849 and enlarged in 1874.

‘Torr Church and Chapel’, a November 1793 watercolour by Rev. John Swete;

‘Torr Church and Chapel’, a November 1793 watercolour by Rev. John Swete;

from where Croft Road now is; Chapel Hill in the background

There are, of course, good practical reasons to build near to a reliable water source. And both Celt and Saxon were also very aware of the hazards of locating their settlement too close to the sea. In addition to protection from the elements and flooding, passing pirates and slavers were forever looking for easy prey. It was wiser to build inland, where a village was less likely to be seen or surprised by a landing party.

But springs were always much more than basic amenities. Indeed, there appears to be a universal human instinct to revere water as it forces its way from the ground. And we can see from the proximity of named springs to Neolithic or Iron Age monuments that veneration for such sites lies deep in our past. We further appreciate the importance of natural springs in the Roman and post-Roman periods; such as at Bath which had medicinal springs at its centre. Christians continued the tradition citing the spring that issued from the staff of Moses and the Well of Beersheba.

Part of the strategy of Christianisation was the conversion and co-option of places that had been of importance to indigenous paganism. In 601 Pope Gregory I wrote to his missionaries amongst the Anglo-Saxons:

Part of the strategy of Christianisation was the conversion and co-option of places that had been of importance to indigenous paganism. In 601 Pope Gregory I wrote to his missionaries amongst the Anglo-Saxons:

“The shrines of idols amongst that people should be destroyed as little as possible, but that the idols themselves that are inside them should be destroyed. … They should be converted from the worship of demons to the service of the true God “.

The landscape then became Christian with specific locations coming under the care of saints instead of pagan deities, with springs being of special significance. Accordingly, during the medieval period it is estimated that there were over 600 Christian holy wells across Britain, many associated with nearby churches.

The landscape then became Christian with specific locations coming under the care of saints instead of pagan deities, with springs being of special significance. Accordingly, during the medieval period it is estimated that there were over 600 Christian holy wells across Britain, many associated with nearby churches.

Water was thought to have healing qualities and some springs became places of special rituals or the focus of pilgrimage, where people prayed and left votive offerings; the tradition of leaving coins and strips of cloth carries on in Totnes (pictured above).

Water was thought to have healing qualities and some springs became places of special rituals or the focus of pilgrimage, where people prayed and left votive offerings; the tradition of leaving coins and strips of cloth carries on in Totnes (pictured above).

Wells seem to have a particular association with fertility, a number gaining a reputation for curing childlessness, or with eye problems. Near St Petrox’ supposed tomb at Padstow is “a spring of living water, which heals eye troubles and inward complaints, if there be faith.”

While there are no records of Torre’s spring as a holy well, other St Petrox sites throughout Devon and Cornwall are celebrated for their healing qualities. Moreover we have nearby evidence of the curative powers expected of local churches.

Across Torbay our medieval churches have strange grooves carved into their outside walls. These can be seen at St Saviours, St Mary the Virgin in Brixham, and Paignton’s Parish Church. It was once believed that these marks had been made by the sharpening of arrows. In Paignton, we even have an old postcard which states, “Marks due to arrow sharpening” (pictured above). However, this is unlikely on pragmatic grounds; the Bay’s sandstone would have rapidly blunted any arrowhead.

Across Torbay our medieval churches have strange grooves carved into their outside walls. These can be seen at St Saviours, St Mary the Virgin in Brixham, and Paignton’s Parish Church. It was once believed that these marks had been made by the sharpening of arrows. In Paignton, we even have an old postcard which states, “Marks due to arrow sharpening” (pictured above). However, this is unlikely on pragmatic grounds; the Bay’s sandstone would have rapidly blunted any arrowhead.

Scholars now believe that there is another explanation for the grooves. All medieval churches, chapels and shrines were considered to have special powers due to their ritual consecration. Across Europe folk traditions describe parishioners scraping powder from church stonework. The dust was then mixed with holy water or wine and consumed as a potion to cure fevers, cancer, and various infirmities; or incorporated in mineral poultices which were applied to injuries.

Our churches and wells were Torbay’s first self-serve pharmacies.

As noted earlier, St Petrox Well was renamed and became Efride’s Well. ‘Efride’ is probably derived from the Old English ‘efre’ meaning ‘ever’. So the appellation is something like ‘ever-running spring’. On the other hand, there are some historians that hold that the “everflowing” stream that keeps being mentioned is actually the Scire Brook that flows from Sherwell Hill via the mills of Old Mill Road to feed the King’s Gardens pond. If this is correct, it was the Reverend James who caused confusion by misnaming the St Petrox well and stream.

While possibly just an error by the good Reverend, this may be a deliberate action. During the Reformation it was assumed that medieval Catholic practices embodied remnants of paganism. As they were closely linked with the cults of the saints, wells were denounced by Protestants and fell into disuse. To decisively sweep the saints influence away, a secular, though familiar, title could have been adopted. James, therefore, may have been maintaining a Protestant convention.

Later, in times less theologically troubled, Efrides seems have attracted the spurious ‘St’ prefix, as in St Efride’s Road. There isn’t, however, a historical St Efride. It may be that the well’s association with the church gave someone the notion that Efride was a real Saxon celebrity; or the name just appealed to the Victorian mythos of an idealised time before the imposition of the cruel Norman yoke.

Later, in times less theologically troubled, Efrides seems have attracted the spurious ‘St’ prefix, as in St Efride’s Road. There isn’t, however, a historical St Efride. It may be that the well’s association with the church gave someone the notion that Efride was a real Saxon celebrity; or the name just appealed to the Victorian mythos of an idealised time before the imposition of the cruel Norman yoke.

Alas, no matter the truth behind the naming of the “everflowing stream”, it flows no more. The spring has ceased to issue from beneath the limestone tor that gave Torquay its name.

Perhaps it was the coming of the railway in 1859 that diverted the subterranean flow, or the construction of buildings nearby. Whatever the cause, the aqueous mother of Torquay dried up in around 1860.

‘Torquay: A Social History’ by local author Kevin Dixon is available for £10 from Artizan Gallery, Lucius Street, Torquay, or:

https://www.art-hub.co.uk/product-page/torquay-a-social-history-by-kevin-dixon