Torquay has always had its ‘Ladies of the Night’, prostitution often being the final resort of desperate women in the town.

Though prostitution was common throughout England in the 19th century, Torquay had its unique characteristics. It was described as the wealthiest in England for its size, and the affluent needed a large servile class. By 1901 18.5 per cent of the population were employed as domestic servants. This saw women far outnumbering men: in 1871 there were 12,772 females to 8,885 males in Torquay.

For those not able to secure employment, there were few alternatives, and prostitutes could be found at night frequenting harbour pubs and Cary Green – the area in front of the Pavilion. The authorities took note when things became too obvious. In 1853 Chief Constable Charles Kilby complained of the “unbecoming manner that young women of the town wander around the thoroughfares without bonnets and shawls”.

This became a long-standing tradition. Even into the 1950s women were still to be found loitering in the area waiting to take their customers to the darker recesses of Rock Walk.

Victorian prostitutes were mainly young, single and aged between 18 and 22. Most had previously held low-wage jobs, often as domestic maids, and some supported illegitimate children. They often worked for short periods and would eventually settle down, many marrying former clients.

Estimates of the number of prostitutes in Victorian England differ depending on who was doing the estimating. In London, the Police claimed there were 7,000, while the Society for the Suppression of Vice said 80,000. A nineteenth century city commonly had 1 prostitute per 36 inhabitants, or 1 per 12 adult males.

Certainly, Victorian Torquay can’t really be compared with London. However, if we take the above ratios, this would give us over 700 Torquay prostitutes. Even at half this number, ‘sex workers’ would have made up a significant part of the working class of our town.

During the nineteenth century, unaccompanied women were often assumed to be prostitutes. For example, in January 1893 the landlord of the Marine Tavern, a one-storey pub situated in front of the Pavilion, was accused of assaulting a policeman and for being drunk and disorderly. However, the defence argued that he was sober and that he had only taken offence when a passing policeman had accused his wife of being “a woman of loose character”.

According to the landlord, he had been waiting at the Fish Quay for the arrival of the ferry which brought in a good deal of custom, leaving his wife unaccompanied. A policeman had approached his wife and that’s where reports differ. The police said the landlord went berserk and had to be restrained by a number of officers both at the Harbourside and later in the police station – the landlord said that he was assaulted and badly beaten. Despite a number of witnesses saying that the landlord was of good character and had not been drinking, and accusations that Torquay’s police had a reputation for being heavy handed, the court accepted the testimony of the police and he was jailed and lost his living.

Generally, the activities of Torquay’s poor were ignored and rarely commented on… unless they attracted the attention of the authorities or reached the courts.

The Victorian reliance on euphemisms in an effort not to offend can also disguise what was really happening. In 1899 the landlord of the Abbey Inn on Abbey Road was charged with allowing his pub to be used as “a habitual resort of women of ill-fame”.

A Detective Thomas watched the Abbey Inn on the night of March 12 between the hours of 8 and 11. “He saw women of loose character enter. They stayed for a considerable time – between 10 and 25 minutes. They entered and returned several times on the same evening, sometimes alone and sometimes in company with men… Entering the Inn, he saw three loose women in one of the rooms.” Unaccompanied women of good character were unlikely to visit an inn and so evidence of impropriety included a notice instructing females not to remain in the house for more than a quarter of an hour.

On one occasion the detective heard the landlord shout: “Time, Ladies!” indicating that women were not being escorted by a man. While being cross-examined, Detective Thomas said: “There is nothing to distinguish them from others except their bad language. The house was a quiet one and perhaps was not likely to attract women of the town in pursuit of their vocation.” In a statement that reminds us of a modern club owner defending ‘drink all you can’ offers, the defendant protested on his arrest: “What can I do with so much rates and taxes to pay. They bring me my living.”

Nevertheless, he was fined £5 with £1 costs and the brewery took away his tenancy.

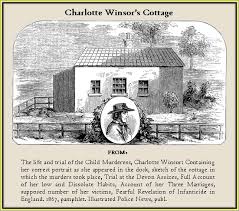

Poverty inevitably lead to the terrible exploitation of the young. From the Torquay Directory of 1870: “Charlotte Winser has long been notorious as keeper of a house in the town of the most profligate character… recruiting even her own daughters for her unholy gain. Their mother has for years made a profit by pandering to the worst vices of others.”

Winser, who had a cottage at Lawes Bridge near where McDonald’s now stands on the Newton Road, was also a baby farmer who killed unwanted infants for payment. On February 15, 1865, the body of Mary Jane Harris’ illegitimate four-month-old son was found wrapped up in a copy of the Western Times beside a road in Torquay.

Miss Harris had farmed out the child to Winsor for 3 shillings a week. At first she had resisted Winsor’s offer to dispose of the child. Yet, when the burden of its support became too much, she stood by and watched Winsor smother her son and wrap his naked body in an old newspaper. The body was later dumped on the roadside.

Trewman’s Exeter Flying Post described the pair as an “un-natural mother and the wretched murderess”.

Testimony revealed that Charlotte Winser conducted a steady trade of boarding illegitimate infants for a few shillings a week or “putting them away” (killing them) for a set fee of £3 to £5. She was sentenced to death, and local entrepreneurs were never one to miss a trick: “It will hardly be credited that men in this town organised excursions offering to take persons to Exeter to witness (Winser’s) execution then back to Newton Races for four shillings.”

Avoiding the death penalty on a technicality, she died in prison of old age after a sentence of 20 years, the Home Office noting that she was among only five prisoners not be released after two decades.

The Charlotte Winser case shocked Victorian Britain. It was used to illustrate a country-wide practice and to campaign for reform. Parliament began to regulate baby-farming in 1872 with the passage of the Infant Life Protection Act. A series of acts passed over the next seventy years gradually placed adoption and foster care under the protection and regulation of the state.

Torquay’s young males were often warned of the dangers of the town. In early 1914 a ‘Big Meeting of Men’ was held in Torquay Town Hall by the YMCA. 800 men attended to hear a series of speakers. They heard that: “Hundreds of lads went under in the moral life every year either through ignorance or curiosity. Filthy picture postcards often led to a loose and unclean life. In Torquay there were thousands of girls and women decking themselves out in bright clothing and donning tawdry jewellery that they might walk the streets and try to attract so-called men and young men”.

Yet, obscure references continued to baffle. When RAF trainees were billeted at the Grand Hotel in 1940, one remembered attending a lecture at which “an ancient aircraftmen” warned them that, “There are lots of ladies down here from London who hand out bags of sweets”. It was only later that the trainees realised what their lecturer had been warning them about!