In a five-minute drive around Torquay you will pass Victorian and Edwardian buildings that encompass a variety of architectural trends from Europe’s past.

While there have been dominant stylistic enthusiasms over the years, architects and their sponsors have always borrowed freely from a range of old and new styles; such as the Gothic, Italianate and Second Empire. They then used them in novel combinations in our homes, hotels and public buildings.

Indeed, as a self-proclaimed international resort, Torquay’s architecture thrived on eclecticism; the practice of deriving ideas, style, and taste from a diverse range of sources.

Indeed, as a self-proclaimed international resort, Torquay’s architecture thrived on eclecticism; the practice of deriving ideas, style, and taste from a diverse range of sources.

That was the whole point of Torquay.

We wanted to give the message to both visitors and residents that they weren’t in England anymore. Here was a new kind of place, a resort located somewhere in a sunnier idealised Europe; though without the Babel of languages, the unfamiliar food, or surly locals. Certainly there would be no discourteous policemen demanding, “Papiere, Bitte”.

There is, of course, a preponderance of the malleable Italianate that could fit in any space available. In 1852 we even designed our Town Hall to look like a palazzo in the Tuscan hills, and in 1874 we designed our Museum in Venetian-Gothic style.

But an even closer neighbour also had a real and lasting influence on our townscape, though we may not have liked to admit it and spent a great deal of effort to disguise those foreign origins. And so, amongst that architectural noise, we get an occasional unexpected glimpse of France.

The end of the Napoleonic wars in 1815 liberated the wealthy from the confines of their home nation, led to a rush across the Channel, and fed a revival of interest in French design. French influences became even more respectable early in the reign of Victoria when the Queen and Prince Albert visited France and patronised European artists, importing Continental trends when building or adding to their own residences. In consequence, many grand private and public buildings of the period have French Chateaux and Renaissance elements, such as gabled dormers, high roofs, chimneys and turrets.

The end of the Napoleonic wars in 1815 liberated the wealthy from the confines of their home nation, led to a rush across the Channel, and fed a revival of interest in French design. French influences became even more respectable early in the reign of Victoria when the Queen and Prince Albert visited France and patronised European artists, importing Continental trends when building or adding to their own residences. In consequence, many grand private and public buildings of the period have French Chateaux and Renaissance elements, such as gabled dormers, high roofs, chimneys and turrets.

These Gallic affectations were to be seen throughout Britain’s country houses and were signs of wealth and education. Yet, while initially confined to the most affluent families, the urban gentry found the impressive skylines met their needs for a dramatic statement. Then the nouveau-riche, keen to be accepted by society, built houses which largely followed the same designs.

It was inevitable that when wealthy visitors came to Torquay to visit their holiday and retirement homes they would wish to reproduce the world they experienced and enjoyed. This brought a combination of architectural elements in a patchwork of often highly ornamented houses.

It was inevitable that when wealthy visitors came to Torquay to visit their holiday and retirement homes they would wish to reproduce the world they experienced and enjoyed. This brought a combination of architectural elements in a patchwork of often highly ornamented houses.

Strongly influenced by French cathedrals and churches was the Gothic Revival. Beginning in the late 1840s, the style drew its inspiration from the pre-industrial rural landscape, and was utilised for its picturesque and romantic characteristics. As Torquay prided itself as having both of these qualities, it was a fitting architecture for the rapidly growing and self-confidant resort.

But the Gothic Revival was more than mere fashion. It was a reaction to change; to the rise of evangelicalism; the industrialisation of Britain; machine production; and the filth and poverty it brought. In response the high church movement sought to emphasise the continuity between the established church and pre-Reformation Catholicism and adopted the imagery in its buildings. Proponents such as Thomas Carlyle and the part-French Augustus Pugin saw medieval society as a golden age. It was effectively a look back in envy, and the approach moved from the ecclesiastical to the domestic and secular.

One advantage of the Gothic was that it could be adapted.

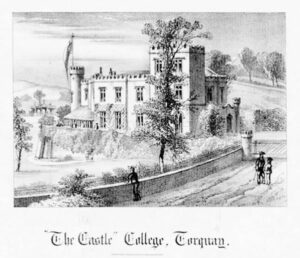

It could create Furze Hill’s great crenellated (battlement-like) Gothic ‘Castle’ which gave Castle Circus its name.

It could create Furze Hill’s great crenellated (battlement-like) Gothic ‘Castle’ which gave Castle Circus its name.

On the other hand, it could mean little more than pointed window frames and mock medieval decorations on terraces using contemporary construction methods and materials. Note the Gothic windows in Belgrave Road and the dragon finials on the rooftops of Union Street.

As a result, the Gothic gave us some very peculiar buildings.

As a result, the Gothic gave us some very peculiar buildings.

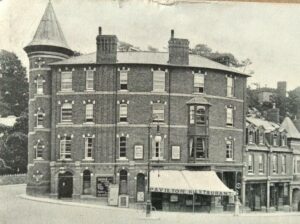

In 1761 Horace Walpole added a French-style round tower to his Twickenham villa in Strawberry Hill. Such tourelles or round turrets with conical roofs could be seen in French castles from the late fourteenth-century onwards, continuing to be built even after their defensive role had passed. We see a Torquay tourelle turning up at Castle Circus. Illustrated is the Woods Pavilion Commercial Hotel around 1900. Sadly, though the building is still there, the turret has long been removed.

In 1761 Horace Walpole added a French-style round tower to his Twickenham villa in Strawberry Hill. Such tourelles or round turrets with conical roofs could be seen in French castles from the late fourteenth-century onwards, continuing to be built even after their defensive role had passed. We see a Torquay tourelle turning up at Castle Circus. Illustrated is the Woods Pavilion Commercial Hotel around 1900. Sadly, though the building is still there, the turret has long been removed.

The Gothic in Torquay also made a political statement as it became associated with conservatism. The best illustration of this is the old Torre Conservative Club by the Police Station. Originally a Constitutional Club, such institutions were founded in the 1880s in anticipation of the electoral reform that was being debated in Parliament.

The Gothic in Torquay also made a political statement as it became associated with conservatism. The best illustration of this is the old Torre Conservative Club by the Police Station. Originally a Constitutional Club, such institutions were founded in the 1880s in anticipation of the electoral reform that was being debated in Parliament.

The pointed arches, gothic detailing, sash windows and the black-painted oriels are all original which gives an idea of its intended function. The Constitutional Club was meant to impress, could be seen from a distance, was on a main route, and would have stood out amongst the surrounding two-storey terraces.

Torquay’s Tory Anglicans and the self-made middle classes already favoured this Gothic style for their suburban domestic residences. They then carried on the tradition in the buildings they sponsored. The message this architecture conveyed followed the new Palace of Westminster (1837-67) and had associations with inherited authority, hierarchy and paternalism. But the Gothic also represented freedom, liberty, individualism and the commercial world. By the 1870s the Gothic had become synonymous with civic identity.

Torquay’s Tory Anglicans and the self-made middle classes already favoured this Gothic style for their suburban domestic residences. They then carried on the tradition in the buildings they sponsored. The message this architecture conveyed followed the new Palace of Westminster (1837-67) and had associations with inherited authority, hierarchy and paternalism. But the Gothic also represented freedom, liberty, individualism and the commercial world. By the 1870s the Gothic had become synonymous with civic identity.

A further inspiration from across the Channel came from the Second Empire style which flourished during the 1852–1870 reign of Louis-Napoleon III. Fittingly, in 1871 Napoleon visited Torquay and stayed at the Imperial Hotel.

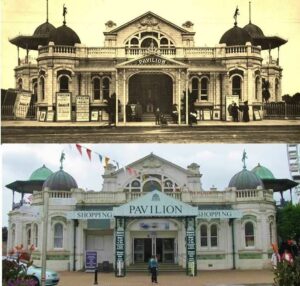

Buildings subsequently became more Italianate though, in contrast to earlier chaotic forms, more balanced, symmetrical, and heavily ornate. Such extravagance was expected to make an impact and gave the British an opportunity to abandon long-held inhibitions and indulge in a variety of embellishments. Following permission to innovate, around the end of the nineteenth century theatres and music-halls were built or remodelled.

This liberation was particularly opportune in seaside resorts looking to excite and attract tourists. Our occasion to impress came in 1911. Both innovative and visually attractive, the Pavilion was built on a concrete raft on land reclaimed from the sea, on which a steel framework was erected. Faced with white tiles, its central copper-covered dome was topped with a life-size figure of Britannia with two smaller domes on each side bearing figures of Mercury. Sculpted Art Nouveau-style cast iron railings edged the steps to the promenade deck and the octagonal bandstands.

Across the nation an English version of the Second Empire style became favoured for those larger hotels being constructed. Most Torquay hotels, however, are conversions of private houses while others, such as the 1866 Imperial, were already established in a firmly Italianate style.

Nevertheless, a particularly useful French import was the Mansard roof. In France, homeowners were taxed by the number of floors in their houses. The Mansard roof, named after François Mansart (1598-1666), became popular because it turned attic space into a liveable extra floor, its dormer windows letting in an abundance of light. This imported novelty was utilised to convert private houses into hotels and guest houses giving parts of Torquay a distinct and much welcomed continental feel.

Nevertheless, a particularly useful French import was the Mansard roof. In France, homeowners were taxed by the number of floors in their houses. The Mansard roof, named after François Mansart (1598-1666), became popular because it turned attic space into a liveable extra floor, its dormer windows letting in an abundance of light. This imported novelty was utilised to convert private houses into hotels and guest houses giving parts of Torquay a distinct and much welcomed continental feel.

Mansards could also give established hotels a way of expanding. In response to the Great Western Railways’ expansion into the South West, the Grand Hotel first opened in Torquay in 1881. Originally with just 12 bedrooms, it is topped with a Mansard roof.

Also somewhat incongruous is Torquay Railway Station. A station serving Torquay had been opened on 18 December 1848, but was some distance from the harbour and the centre of the town. A new station near Abbey Sands was opened on 2 August 1859. Renamed ‘Torre’, the original station continued to support goods traffic. The new Torquay Station clearly needed to offer a more sophisticated welcome to passengers. Accordingly, an improved station was opened on 1 September 1878. The design suggests a miniature French chateau.

Also somewhat incongruous is Torquay Railway Station. A station serving Torquay had been opened on 18 December 1848, but was some distance from the harbour and the centre of the town. A new station near Abbey Sands was opened on 2 August 1859. Renamed ‘Torre’, the original station continued to support goods traffic. The new Torquay Station clearly needed to offer a more sophisticated welcome to passengers. Accordingly, an improved station was opened on 1 September 1878. The design suggests a miniature French chateau.

Of course, if we want to visit an example of explicit French influence we have Oldway Mansion. Around 1871, the Fernham estate in Paignton was purchased by Isaac Singer who died on 23 July 1875, shortly before work on the original mansion was completed. Paris Singer, a son of Isaac, supervised the alterations at Oldway between 1904 and 1907. The rebuilding work was modelled on the Palace of Versailles and the eastern elevation of the building was inspired by the Place de la Concorde in Paris.

Of course, if we want to visit an example of explicit French influence we have Oldway Mansion. Around 1871, the Fernham estate in Paignton was purchased by Isaac Singer who died on 23 July 1875, shortly before work on the original mansion was completed. Paris Singer, a son of Isaac, supervised the alterations at Oldway between 1904 and 1907. The rebuilding work was modelled on the Palace of Versailles and the eastern elevation of the building was inspired by the Place de la Concorde in Paris.

The influence of all forms of Revivalism peaked by the 1870s. And while there were always those mournfully looking back to the glories of a fading Empire, new architectural movements were gaining ground. Torquay was discarding past historical styles to embrace the Modern Movement. Utilising advances in engineering and building materials, Modernism rejected ornamentation or decoration and promoted minimalism, the use of simple design elements. One example is the 1937 Queen’s Hotel, described as, “Torquay’s contribution to the Jazz Age aesthetic”.

The influence of all forms of Revivalism peaked by the 1870s. And while there were always those mournfully looking back to the glories of a fading Empire, new architectural movements were gaining ground. Torquay was discarding past historical styles to embrace the Modern Movement. Utilising advances in engineering and building materials, Modernism rejected ornamentation or decoration and promoted minimalism, the use of simple design elements. One example is the 1937 Queen’s Hotel, described as, “Torquay’s contribution to the Jazz Age aesthetic”.

Torquay never ceased importing architectural styles. Though today, the Spanish hacienda and the colonial bungalow are perhaps more de rigueur.

Eclectic Torquay continues to pillage the world for its architecture and to fill its parks and gardens with exotic flora. But whatever the evolutions in style, the message remains always the same, “You’re not in England any more”.

(The Mock Turtle is a character from ‘Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland’ by Lewis Carroll. The Mock Turtle is a pun on mock turtle soup, a cheaper imitation of the expensive green turtle soup favoured by the very rich. The Mock Turtle is a very melancholy character that pines pathetically for the days when it was once a real turtle.)

‘Torquay: A Social History’ by local author Kevin Dixon is available for £10 from Artizan Gallery, Lucius Street, Torquay, or:

https://www.art-hub.co.uk/product-page/torquay-a-social-history-by-kevin-dixon