“Old ladies in wheelchairs with blankets over their legs, I don’t think so… they’re retired mermaids”, Milton Jones

Mermaids have long featured in the folklore of the sea. They traditionally have the head and upper body of a female human and the tail of a fish.

Sometimes they are unlucky omens, maybe foretelling disaster in the form of approaching rough weather or even causing it through shipwreck.

At other times, mermaids act as the guardians of sailors, swimming alongside a ship to guide its passage or by protecting a mariner they love.

Mermaids are indeed wilful and capricious. A trait that can get them into trouble with their line manager.

The Zennor mermaid carved in a fifteenth-century wooden bench in the local church

On occasion, mermaids come ashore. In the Cornish village of Zennor, legend tells of an amorous aquatic falling in love with a local man, finally taking him back to her watery home. On summer nights, the lovers can still be heard singing together. The Zennor mermaid can be seen carved in a fifteenth-century wooden bench in the local church.

The actual logistics of fish-human intimacies are, however, perhaps best left to the imagination.

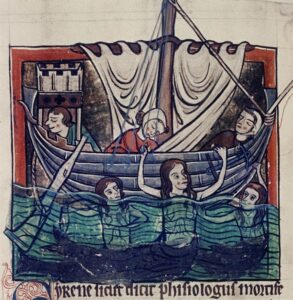

Are they out there still? Mermaids in a thirteenth century English mansucript

So, do we have any real evidence that mermaids exist and are maybe still out there in the Bay?

Perhaps.

It is said that, when a mermaid sheds a tear, these can be found washed up on our beaches in the form of translucent beads. These shimmering affirmations of marine despair are then discovered by beachcombers.

We aren’t recommending you do this, but if you put one of these beads in your mouth you can supposedly taste the bitter residue of those weeping sea-maidens.

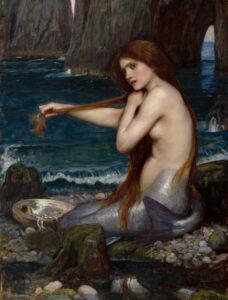

A Mermaid (1900) by John William Waterhouse, inspired by Torquay visitor Lord Tennyson’s 1830 poem

Some mermaids have lot to cry about due to having fallen out with their god. This is Neptune, the god of the sea in the Roman religion. He is the counterpart of the god Poseidon in the Greek tradition and brother to Jupiter and Pluto with whom he presides over the realms of heaven and the earth.

Neptune is also the controller of winds and storms, and mermaids are his maidens. They are forbidden to change the course of nature, but some nevertheless defy this instruction by trying to save sailors in peril, so thwarting Neptune’s will.

Even worse, some mermaids have been known to fall in love with a pirate, sea captain or sailor. As punishment, a jealous Neptune then banishes the disobedient mermaid into the depths of the seas.

Unable to now rescue those lost at sea, the mermaids now cry tears that turn into crystalline drops, which are ultimately swept ashore by the waves.

Other lore states that mermaids can only come on shore in the light of the full moon. As dawn breaks, they shed even more tears as they are obliged to return to the seas. These hardened tears are in the colour of the mermaid’s eyes and are treasured and kept forever in the pockets of their lovers. Alternatively, they were utilised by local folk as they told romantic and profitable tales to tourists during the nineteenth century.

There is, you may not be surprised to hear, an alternative explanation for those translucent finds on the Bay’s beaches.

They are merely fragments of discarded glass, broken into shards and over decades tumbled by the combination of waves, sand, and rocks. Minerals in the water contribute to the weathering process, giving the glass its characteristic frosted appearance and its irregular shape.

And it certainly takes a long time. Sea glass can take anywhere from seven years to two hundred years to form, depending on its size and thickness.

The appearance of the glass is determined by its original source, so the most common colours are green, brown, and white and clear. These can come from bottles of beer, juices, soft drinks and even old-style fishing floats.

Less common colours include amber, from bottles of whiskey, medicine, and spirits; or green and blue from bottles for medicine, ink, and fruit jars.

A gem in reverse: sea glass found near Torquay’s Corbyn Head

A gem in reverse: sea glass found near Torquay’s Corbyn Head

Nowadays, sea glass is used for decoration, most commonly in jewellery. And here we have a gem in reverse. Where regular gems are made by nature and then refined by humans, sea glass is man-made but then refined by nature.

Hence, some of us see a metaphor in a specific piece of sea glass we may have found at a time of personal rediscovery.

Each fragment has been on its own journey. Once made by other men and women but broken and discarded and then over many years transformed and made beautiful, whole and valuable once again; a real sea-change into something rich and strange. Those of us fortunate to live by the sea then take this as a message about life.

The real value of sea glass is its journey, its history. Each piece of sea glass holds a story, and questions about its origin. How old is it? Who touched this piece of glass before I did? What was it before? A vase? A bottle? A jar once filled with something? Who owned it? How did it end up in Torbay?

Often, sea glass experts can come close to identifying what a piece of sea glass used to be by its colour and occasionally by any other markings.

But beware. People do try to artificially create sea glass by using rock tumblers. Sea glass experts can, however, tell the difference; the long years of tossing and tumbling in the ocean cannot be reproduced. Most commercial shop-bought ‘sea glass’ is manufactured so do look out for mislabelled fakes. The giveaway is anything perfectly shaped. Anyway, it’s so much more satisfying to find your own on a local beach. But these days beach gems are getting harder to find, the amount and variety dramatically reducing over the past few decades. Before the mid 1960’s, much of everything came in glass bottles, jars, or tin cans. Coastal residents would bury their rubbish near beaches while passing ships would simply toss their empty bottles into the Bay.

But these days beach gems are getting harder to find, the amount and variety dramatically reducing over the past few decades. Before the mid 1960’s, much of everything came in glass bottles, jars, or tin cans. Coastal residents would bury their rubbish near beaches while passing ships would simply toss their empty bottles into the Bay.

Now glass is used less due to plastics and much-needed recycling. Throwing bottles directly into the sea or smashing them on rocks, satisfying though that may be, is now frowned upon.

So do keep a look out for these beautiful little glass pebbles. Indeed, feel free to find some and take them home. You’re even doing the marine environment a favour. Unlike other seashore finds, sea glass is a human product and considered litter, not a natural resource. It is therefore not protected under the 1949 Coast Protection Act.

That’s what those opaque fragments lying on our beaches actually are. Just our detritus that we have romanticised and turned into jewellery and keepsakes. They’re not the tears of an exotic sea species, forever mourning a forced separation from their terrestrial lovers.

Unless, perhaps, this is another layer of misinformation, a further cruel punishment decreed by Neptune. That our amphibious cousins be forgotten forever by the men that once loved them…

‘Torquay: A Social History’ by local author Kevin Dixon is available for £10 from Artizan Gallery, Lucius Street, Torquay, or:

https://www.art-hub.co.uk/product-page/torquay-a-social-history-by-kevin-dixon