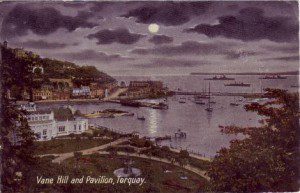

From its very beginnings as a town, Torquay had a significant gay population. As in many other coastal towns, the gay community had its roots in the presence of the Royal Navy and the local maritime tradition.

Contributing to this was Torbay’s large sheltered anchorage which was used by the Royal Navy’s Channel Fleet. Sailors, of course, didn’t spend all their time singing sea shanties and tying knots. In any environment in which males live in close quarters for extended periods, homosexuality was well known. For that reason, the Royal Navy during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries was defined as the home of ‘rum, sodomy, and the lash’. One Victorian naval officer remembered: “I have been stationed, as you know, in two or three ships….On the D—, homosexuality was rife, and one could see with his own eyes how it was going on between officers… nobody was ‘shocked’ on board either the A— or the B—. There were half a dozen ties that we knew about.”

While it was the visiting wives and relatives of naval officers that initiated Torquay as a tourist town, it was the Napoleonic wars that really led to the town’s rapid growth as a resort. The rich, denied their visits to continental Europe, were compelled to find leisure closer to home and so Torquay grew into a premier health resort. From a small fishing village with a population of 838 in 1800, 50 years later Torquay’s population stood at 11,474. Many thousands more would visit depending on the season. As the town grew, so did its gay community.

For many years, being gay meant leaving family and going to a place more accepting. For some gay people this meant journeying to a city, while for others spa and health towns became a favoured destination. Both could offer anonymity and for the prosperous, Torquay was an attractive destination – during the 1880s the resort was described as the wealthiest in England.

Along with other pleasure-towns, such as Brighton, Torquay acquired a reputation for Bohemianism. Like-minded people gathered around musical, artistic, or literary pursuits. For the less well-off, the town could offer work, even for the unskilled. Domestic staff could also live in, solving the problem of accommodation – by 1901 18.5 per cent of Torquay’s population were employed as domestic servants.

Once the town had established a reputation as somewhere gay people could live and find companionship, more gay people came to the Bay.

We don’t know, however, the actual numbers of gay people in nineteenth century Torquay. Homosexuality was still considered a serious criminal offense, punishable by a long prison sentence or even by hanging. In fact, in 1806 there were more hangings in England for homosexuality than for murder. Consequently, gay people learned to be discrete. Yet, we may be able to see some indications of a large local gay community.

For example, there were an unusual number of spinsters and bachelors living alone, and of single women and men living with elderly relatives. There were also many men and women who described themselves as writers or artists. It’s even been suggested that a few Torquay villas were specifically designed with a second, less public, entrance for ‘gentlemen callers’.

And, of course, we do know of many gay visitors and residents. To be sure, the most famous scandal of the nineteenth century began in Torquay. It was at Babbacombe Cliff during the winter of 1892/93 that Oscar Wilde (1854-1900) completed his plays ‘A Woman of No Importance’, ‘Salome’ and ‘Lady Windemere’s Fan’. During this visit, Oscar was joined by his lover Lord Alfred (Bosie) Douglas. In 1895, Bosie’s father, the Marquis of Queensberry, made allegations of homosexuality against Wilde. Oscar sued for libel, but lost. After details of his private life were revealed during the trial, he was arrested and tried for gross indecency. He was sentenced to two years of hard labour in Reading Gaol. Upon his release, Oscar left for France, never to return. He died destitute in Paris at the age of 46.

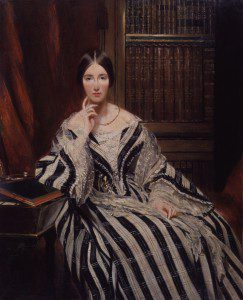

Sometimes we can only assume sexual orientation. For example, local resident and philanthropist Angela Burdett-Coutts (1814-1906) was devoted to her companion Hannah, and they were socially recognised as a couple. When Hannah died in 1878, the Baroness (pictured above) said she was crushed by the loss of, “my poor darling, the companion and sunshine of my life for 52 years”. Was this a gay relationship or a deep friendship, and does it matter?

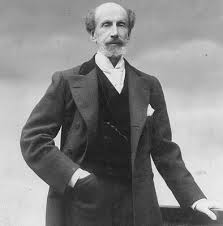

Even being married wasn’t a reliable indication. Oldway’s Winnaretta Singer (1865-1943) was long married to Prince Edmond de Polignac (1834-1901) in what was widely accepted as a Lavender Marriage – a union of convenience between a lesbian and a gay man. That’s Edward above and Winnarretta below.

Unfortunately, being gay in Victorian and Edwardian England often involved feelings of guilt. The St Marychurch poet, author and critic, Sir Edmund Gosse (1849-1928) found his sexuality a burden. Edmund was the son of the Creationist Philip Henry Gosse. Indeed, we know much about the elder Gosse from Edmund’s autobiography ‘Father and Son’ (1907) in which he recounts his escape from the dominance of a puritanical father. Edmund relates how, as a boy, he had been taken by his father to Torquay where he attended local schools. Though he lived in a strict religious household, Edmund (pictured below) secretly became familiar with nonreligious poetry, fiction, and other literature. On leaving Torquay, he secured employment on the library staff of the British Museum, was a translator for the Board of Trade for some 30 years, lectured on English literature at Trinity College, Cambridge and was librarian to the House of Lords from 1904 to 1914. He also translated three of Ibsen’s plays, wrote literary histories, as well as biographies of notable writers. In August 1875 Edmund married Ellen Epps (1850-1929), a young painter in the Pre-Raphaelite circle. Edmund and Ellen had a happy marriage lasting more than 50 years and they had three children. This was despite Edmund (pictured left) being gay. He wrote to a friend: “I have had a very fortunate life, but there has been this obstinate twist in it!”

Vocation also seems to have been no indicator of sexuality. Torquay’s Anglican clergyman Reverend Edwin Emmanuel Bradford (1860–1944) wrote copious quantities of homoerotic poetry (example below). Many of his poems are directed towards young males who go by the names of Willie, Eric, Dick, Guy, Frank, Jock, Aubrey and Silvester. Edwin’s prose was very popular during his lifetime, with WH Auden and John Betjeman being admirers, and he is now recognised as a leading gay poet of the early twentieth century. Remarkably, however, it doesn’t appear as if the Bishop ever noticed what his Torquay vicar was writing!

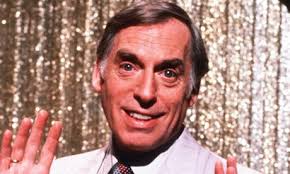

As a tourist resort, we have hosted some of the highest profile stars of stage and TV screen. For several years in the mid-80s Torquay was home to Larry Grayson (1923-1995), best remembered for hosting the BBC’s game show ‘The Generation Game’, and for his high camp humour which featured his catchphrases such as “Shut that door!” and “What a gay day!” Larry’s friends included fag Ash Lil and Everard – say it slowly. Larry (pictured below) was one of the first television comedians to suggest being openly gay. Indeed, his early TV appearances had led to many complaints about his act being too risqué and he feared that he would never make it on TV.

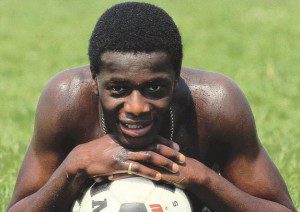

Torquay United in 1991 also led the way in signing the first openly gay player, the talented Justin Fashanu (right). Justin played 21 league games that season and scored 10 goals. He was, however, a complex character and a magnet for the tabloid press due to his high profile. He was the first black footballer to command a £1million transfer fee with his transfer from Norwich City to Nottingham Forest in 1981. Yet, it was his sexuality that attracted most sensationalist attention. In 1990, he publicly came out as gay in an interview with the tabloid press, becoming the first prominent player in English football to do so. The headline in The Sun screamed: “£1m Football Star: I AM GAY. Justin Fashanu confesses”. Note the use of the term ‘confesses’ – the verb, “to admit that one has committed a crime or done something wrong”. Although Justin claimed that he was accepted by his fellow players, he admitted that they would often make jokes at his expense. He also became the target of constant crowd abuse. Tragically, Justin took his own life in 1998.

Being gay in Torquay wasn’t to be in a safe and supportive environment, however. To take one of many examples, in September 1926 two local men stood trial for inflicting serious bodily harm on Clifford E Skitt, a chauffeur of Buckingham Street, Westminster. Torquay Police Court heard that Clifford experienced an assault described as an “unprovoked and dastardly outrage on an undefended man”. This was, “one of the most brutal and ruffianly the Bench had ever had before them”.

The two accused were labourer Joseph Jones and auxiliary postman Charles Brown, both of Happaway Court. The victim, a “highly respectable married man with a wife and one child… whilst walking quietly along the Strand was suddenly set upon and knocked down by the defendants.” In court Clifford said that he was making his way towards the Imperial Hotel where he was staying. As he walked along the Strand he, “noticed two young men walking in front of him. When he got level with them, one of them gave him a severe blow in the eye, and he fell down stunned. When he came round and got up, Jones, who appeared to be helping him, gave him a blow in the face.”

Police Sergeant Potter found the two defendants later that night on Torre Abbey Sands. After first denying they had been in the Yacht Hotel, Brown said, “I don’t know about an assault, but I punched a Nancy boy. He wanted me to go for a walk and I hit him”. Brown’s later written statement read, “The man I hit is more of a woman in disguise than a man. I hit him with my fist, coming from the Yacht Hotel, and I know he fell over. The only reason I punched him was because he asked me to go for a walk with him.”

Jones didn’t help his defence by stating, “One of the Nancy boys said to me ‘Would you like to go for a walk with me, love’, and Brown hit him. That is all. We plugged him, and the hospital is the place for a man like that”.

Brown was fined £5 or 21 days imprisonment with hard labour. Jones already had a criminal record, having served a month’s imprisonment in Brighton for receiving stolen property. Accordingly, he was sent to prison for six weeks with hard labour. The severity of the sentences given to Brown and Jones were probably associated with their threat to general public order – Torquay wasn’t unfamiliar with street brawls. They further involved the crime of working class violence carried out by locals against a respectable tourist who had the ability to afford to stay at the Imperial.

This assault wasn’t unusual. Throughout the 20th century many thousands of gay men were assaulted, blackmailed, prosecuted, sentenced to prison and shamed – including Alan Turing, who helped break the Enigma code, and who committed suicide shortly after his prosecution.

Indeed, it’s worth noting that Clifford was under just as much threat of arrest and imprisonment as were his two assailants. Homosexuality was a crime until 1967, when the Sexual Offences Act was passed by the Labour government under Prime Minister Harold Wilson. The act decriminalised homosexual acts ‘between consenting adults in private’, though it wasn’t until 1994 that the age of consent for gay men was reduced to 18, and then to 16 in 2001.

From our very beginnings as a town, Torquay has had an LGBT community. Equality took a long time and had to be fought for. For many years our gay community had to be discreet. Now, in these more enlightened times, there’s certainly a gay history of Torquay waiting to be written!