“Here I sitting behind in a dark place, a lady spit backward upon me by a mistake, not seeing me, but after seeing her to be a very pretty lady, I was not troubled at it at all”, Samuel Pepys (1633-1703)

Social attitudes change – sometimes we know why, while other changes have less obvious reasons.

One particular behaviour was once seen as normal across the Bay, and viewed as only unpleasant just a few weeks ago. Now it is seen as being positively dangerous, a weapon, and even an extreme form of attack. That practice is spitting in the street.

Not spitting is a largely recent phenomenon. In the villages of our medieval and early modern Torbay frequent spitting was part of everyday life, it was even thought very ill-mannered to swallow saliva to avoid spitting. It was normal at all levels of society there are reports of people sitting and spitting in Parliament right up to the end of the nineteenth century.

Indeed, before the advent of sewers in Torquay, Paignton and Brixham, everyone spat in the street – they did much worse. There was even a well-known piece of furniture that facilitated spitting indoors. This was the spittoon, a container for saliva which could be found inside many public places, such as inns and pubs, as well as private homes.

It’s only relatively recently in British history that spitting has become taboo.

Certainly there were always some health risks associated with expectoration but in normal times the chance of catching a contagious disease by even being spat on is low. Now spitting has deeper meanings. As it represents something unnecessary, spitting is symbolic and can be seen as a way of displaying anger, marking territory, indicting contempt or just showing off. It’s now even a form of attack designed to elicit revulsion. The police say “in most cases, spitting if done deliberately will be an assault” and have introduced spit hoods to protect officers.

Spitting is also class-related. By the early 1700s, spitting had become seen as something which should be generally concealed in elite society. Our upper classes began to differentiate their behaviour from the working classes in a variety of symbolic ways and spitting was one of those practices – by 1859 it was described by an etiquette guide as, “at all times a disgusting habit.” In contrast, working class pubs had spitting troughs at the base of the bar right up until the 1930s.

There may be remnants of this class distinction in sport.

Note how footballers regularly spit even when they haven’t been running or have even started the game, while tennis players rarely spit. However, there are clear rules. On the football pitch, spitting on the ground is accepted but spitting at your opponents is categorised as “violent behaviour” by world governing body FIFA.

So why did our attitudes to spitting change?

Torquay was one of the places where this rapid acquisition of an aversion to spitting was most obvious. It was the awareness of an association between spitting and disease that caused such an evolution in behaviour.

In 1840 Dr AB Granville visited Torquay and described a town of the sick and dying.

He wrote, “The Frying Pan along the Strand is filled with respirator-bearing people who look like muzzled ghosts, and ugly enough to frighten the younger people to death”. Torquay was, “the south west asylum for diseased lungs”.

The hotels were, “filled with spitting pots and echoing to the sounds of cavernous coughs, while outside the only sound to be heard was the frequent tolling of the funeral bell… awful and thrilling to the rest who were trembling on the verge of their grave with symptoms of the same devouring malady, Consumption”.

This was tuberculosis which killed one in seven people in the US and Europe during the late 1800s, making it the deadliest infectious disease at the time. Torquay marketed itself to TB sufferers as a health resort but, crucially, the disease was not recognised as communicable in the early nineteenth century. Effectively, the town owes its early development by acting as an unwitting Petri dish for this deadly disease.

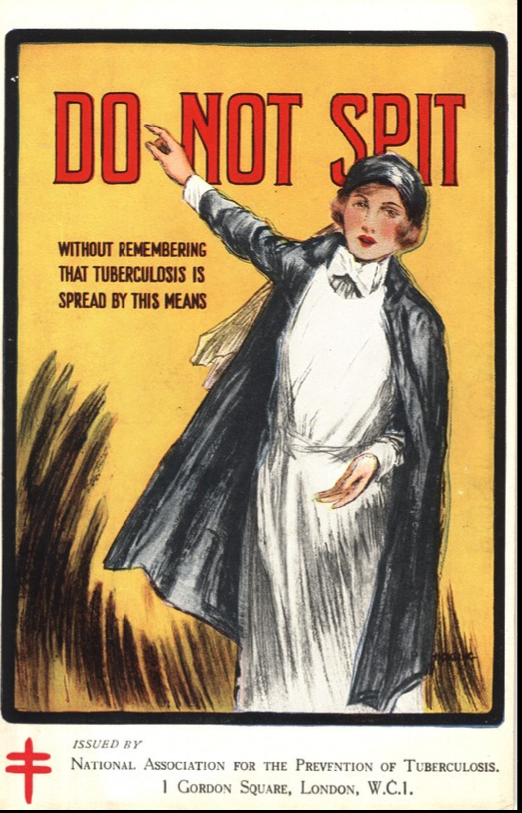

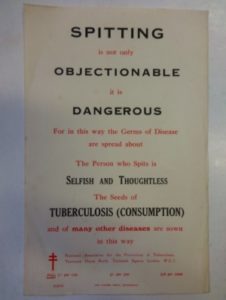

In 1882, the German bacteriologist Robert Koch linked tuberculosis to a bacterium and enabled public health campaigns to prevent its spread. This also ended Torquay’s days as a health resort targeted at those with the contagious disease. Even though there was little evidence that spiting itself caused more cases, ‘Do not spit’ became a well recognised instruction on campaign material and it was common to see “spitting prohibited” signs on buses.

The other great health challenge was the 1918 Spanish Flu outbreak which killed more people than the Great War.

As the incidence of TB declined and the influenza outbreak faded from memory, spitting became to be seen as less of a public health issue and more one of politeness and an overt display of underclass self-awareness- punks ‘gobbed’ at bands on stage. Even though until 1990 spitting was an offence carrying a £5 fine, it seemed to cause little public concern as its symbolism declined in importance.

But by the early years of the twenty first century spitting again became a focus of disquiet and the idea of punishment and fines for spitting re-emerged.

In 2013, Enfield council in London introduced a by-law to make spitting in public illegal and two young men were prosecuted – spitting was defined a sub-genre of litter. This new anxiety was possibly due to spitting having become much more common due to immigration from places where public spitting was the norm.

And it’s worth noting that spitting remains normal in some parts of the world. It’s commonplace or even expected. Maasai tribes in East Africa greet each other through spitting, though possibly the three most significant spitting nations are India, South Korea and China. The reasons seem to be different for each: spitting in India is connected to the chewing of betel nut; in South Korea it’s closely linked to smoking.

In China spitting is simply a convenient way of removing something unpleasant from one’s mouth. On the other hand, the rapidly urbanising nation has attempted to tackle the issue a number of times. Ahead of the 2008 Beijing Olympics volunteers handed out special ‘spit bags’ while banners across the city urged people not to spit as a way of “improving manners”.

Now, spitting is again being seen as totally unacceptable and, indeed, dangerous. Thankfully, as a consequence of community distaste and, if required, legal sanction, public spitting is unlikely to be seen again in Torbay for some time to come.

You can join us on our social media pages, follow us on Facebook or Twitter and keep up to date with whats going on in South Devon.

Got a news story, blog or press release that you’d like to share or want to advertise with us? Contact us