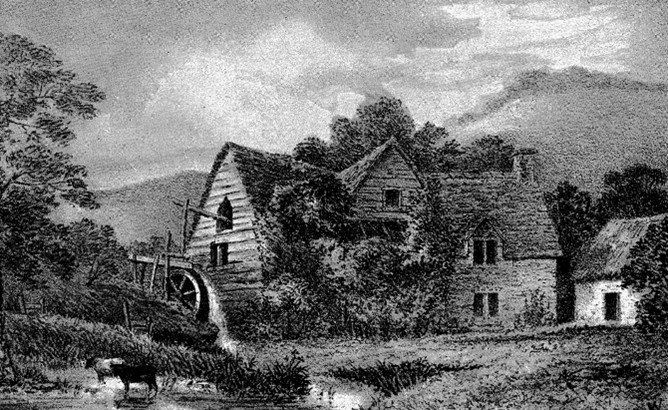

The Fleete Mill in 1793 by Reverend JB Swete: just about where WH Smiths now is

Behind Torquay harbour two narrow valleys stretch back from the waterfront. In the west, Fleet Street links the commercial centre of Torquay with the Strand. It takes its name from the Flete Brook which rises in Combe Pafford to flow south through Upton. The Fleet then turns southeast to funnel through a narrow limestone valley bounded by Torre and Waldon Hill to the south, and Furze and Braddon Hills in the north.

Long confined underground, the Fleet concludes its journey unseen at the harbour. Though now mostly forgotten, this watercourse was the mother of modern Torquay.

Beginnings

The name is derived from the Anglo Saxon ‘flēot’ meaning ‘tidal inlet’. Since the inlet only ran so far inland, however, this raises the question over whether the whole of the river was always known as the Fleet.

The first mention we have is in the 1556 will of Symon Wheler of Torre which bequeathed “all my salt in my cellars at Flyett”. In 1608 we have records of a grant of land, “and another house and dye mill lately erected and built by the said John Saunders at Fleete within the tithing of Tormohun”.

Going further back, it is believed that the Fleet was being utilised to grind corn at the Fleet Mill by the end of the thirteenth century. This site of the mill is close to where WH Smiths is now.

The mill was demolished in 1835 but we do have a late eighteenth-century watercolour painted by the Reverend JB Swete. It shows the mill with a waterwheel in a steep valley with cows grazing in the foreground; the mill pond is in Pimlico. That bucolic scene would change during the nineteenth century when the vale sustained extensive quarrying to cater for Torquay’s swift expansion.

Late nineteenth century Castle Circus; the Fleet on the lower right

There were only two other houses nearby in the early years of the nineteenth century. One was occupied by a lime burner named Frank Short, the other was lived in by a gardener by the name of William Stentiford. From this, we have Stentiford’s Hill, one of the few local places not named after the aristocratic Carys, Palks, Mallocks, and their various relatives.

Incidentally, the original name was Happaway Hill where there was a deep cave. An exploration took place in October 1862, but Happaway Cavern was soon after quarried away so we’ll never know if it contained any archaeological treasures.

Over the years the landscape through which the river flowed has changed significantly. Alongside extensive limestone quarrying which widened the valley, the Fleet was culverted allowing for building. Old illustrations show two small stone piers and a few houses, indicating that by the late eighteenth-century the inlet had been tamed and reclaimed.

And so, by 1803 ‘Trewman’s Guide to the Watering Places to the SE Coast of Devon’ could describe “neat cottages with small gardens and several modern built lodging houses, nearly as pleasant as those on the beach”. The Reverend Swete was less complimentary describing “an insignificant row of houses, that skirts the brook side and blocks it up to the sea”. These narrow lanes were Swan and George Streets which now lie buried beneath Fleet Walk.

The overground Fleet in Upton

As a source of drinking water, the Fleet and its tributary Ellacombe’s brook were crucial to the town’s development. But the Fleet also took sewage out to sea via the harbour and so carried disease.

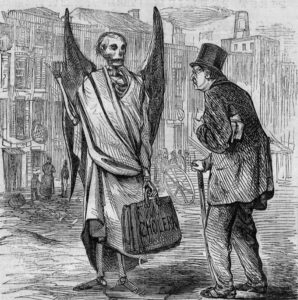

In 1832 and 1849 cholera came to Torquay

In 1832 and 1849 cholera reached Torquay. The latter outbreak lasted for six weeks leading to 66 deaths mainly in the oldest and impoverished parts of town, Pimlico, Swan Street and George Street. For example, in Pimlico, where the traffic now runs to avoid the pedestrianised Lower Union Street, a population of over 200 lived in overcrowded conditions. Many of the dead were anonymously buried in a mass grave in Torre churchyard known as Cholera Corner.

A growing awareness of the dangers of such waterborne diseases caused Torquay to adopt the Public Health Act, the first meeting of the Local Board of Health taking place in September 1850.

Forcing the Fleet underground near Penny’s Cottage

Conditions then gradually began to improve with the Board making “a good wide street between the bottom of Union Street and the Strand” to replace the narrow alleyways on both sides of the Fleet. At the same time, the river was confined to a tunnel which from then on flowed unseen toward its ultimate destination, the Strand, from the Old English ‘strond’ meaning the edge of a river.

Today, the Fleet remains underground, and the broad highway still runs through Torquay from Castle Circus to the Strand. Though you can’t see it, you can often hear the Fleet rushing below you if you stand outside Primark.

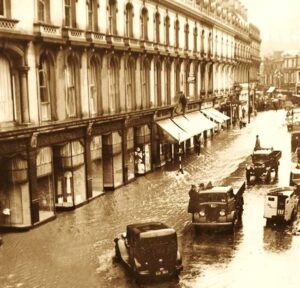

But never forget that the mother of Torquay also has a temper. While normally serene and discrete, high tides and heavy rain on many occasions brought her waters to street-level. This required the construction of storm tanks to cope with town centre flooding. Whether these precautions will always be sufficient depends on climate change and rising sea levels in the future.

Final destination: Torquay’s Strand in 1780

Ultimately, all history is about individuals, those who inhabit and shape the land they live upon. So, let’s take a glimpse into the life of a Torquinian. Not someone who lived amongst the great and good of the Victorian resort, but a man who resided amongst the poorest.

Here’s the story and a slight correspondence with a well-known movie.

In the classic 1994 film ‘The Shawshank Redemption’ Andy Dufresne, played by Tim Robbins, is sentenced to life in Shawshank State Penitentiary. At the end of the film, the prison guards find his cell empty. Taking 19 years Andy had dug a tunnel with a tiny rock hammer to make his escape.

Torquay had a similar escape artist… well, almost.

Torquay’s original Town Hall is opposite WH Smiths in Lower Union Street. The building also doubled as our local lock-up for criminals of all types. Known as ‘the Clink’, it occupied the Town Hall’s lowest level, and the cells are still there.

During the late 1850s one local resident was regularly being “locked up for one cause or another”. This was Tom Moxhay who was described as “a half-witted man”. Tom seems to have been a bit of an escape artist and on one occasion “he knocked away the bolts of his cell door with his bedstead and got away”. He was soon recaptured. Nevertheless, a bit like Steve McQueen’s Cooler King in ‘The Great Escape’, this didn’t put him off. Sorry about mixing movie metaphors there. It’s his other escape that reminds us of Shawshank’s Andy Dufresne. The newly enclosed Fleet, now functioning as a sewer, ran underneath the cells and, “half-witted” though he may have been, Tom managed to remove some stones to access a subterranean escape route.

It’s his other escape that reminds us of Shawshank’s Andy Dufresne. The newly enclosed Fleet, now functioning as a sewer, ran underneath the cells and, “half-witted” though he may have been, Tom managed to remove some stones to access a subterranean escape route.

From his cell Tom crawled in the foul darkness underneath the entire length of Fleet Street and emerged at the harbour. Sadly, for modern romantics, he was there recaptured. Bearing in mind the route of Tom’s daring bid for freedom, we can assume that none of our law enforcers would have wanted the honour of taking him back into custody: “You can have this one…”

The Fleet, needless to say, can act as a metaphor. The mother of Torquay carved the landscape, was utilised by many generations, but could give rise to illness and death. She was essential as a cluster of hamlets evolved to become the richest town in England. When her services were no longer of use, her flow was forced underground and forgotten.

Flooding in Fleet Street

Though still, on occasion, she would make her presence known. Not always would the Fleet remain patiently beneath our feet, and we may well see her wrath again as sea levels rise.

Torquay: A Social History’ by local author Kevin Dixon is available for £10 from Artizan Gallery, Fleet Street, Torquay, or:

https://www.art-hub.co.uk/product-page/torquay-a-social-history-by-kevin-dixon