Torquay’s St Michael’s Chapel is a mystery.

We don’t know who built it and what it was for, and we don’t have any written record of the chapel. It isn’t recorded in any of the Abbey’s title deeds, known as cartularies.

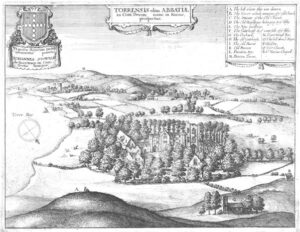

There is even some confusion over what the chapel was originally called. In 1661 Wenceslaus Hollar’s issued an engraving, ‘Monasticon Anglicanum’ by William Dugdale. It was titled, ‘A prospect of Torre, once an abbey in the county of Devon, now in ruins’. At the bottom right of the image is the chapel, identified as ‘R’, ‘St Marie’s Chapell’.

Today it is known as St Michael’s Chapel. And this may give us a clue as to the building’s original function.

Today it is known as St Michael’s Chapel. And this may give us a clue as to the building’s original function.

The chapel is dated to the thirteenth or fourteenth centuries, presumably built and operated under the supervision of the nearby Torre Abbey, and likely went out of use around 1539 when the Abbey was closed.

Chapels aren’t uncommon, around 4,000 parochial chapels were built between the twelfth and seventeenth centuries. On the other hand, the building’s uneven floor is out of the ordinary. Someone spent a great deal of time, money, and effort on constructing the chapel and then not levelling the floor. This has led to the proposal that the limestone summit was the site of a religious vision; the chapel then being constructed around this event. Hence, the limestone was left untouched as this was sacred ground.

Chapels aren’t uncommon, around 4,000 parochial chapels were built between the twelfth and seventeenth centuries. On the other hand, the building’s uneven floor is out of the ordinary. Someone spent a great deal of time, money, and effort on constructing the chapel and then not levelling the floor. This has led to the proposal that the limestone summit was the site of a religious vision; the chapel then being constructed around this event. Hence, the limestone was left untouched as this was sacred ground.

Regarding the name given in the engraving, after Christianity spread across the Roman empire, Maria became the Latinised form of the name of Miriam; Marie is the French version. In English it is ‘Mary’, and refers to Mary, mother of Jesus.

Regarding the name given in the engraving, after Christianity spread across the Roman empire, Maria became the Latinised form of the name of Miriam; Marie is the French version. In English it is ‘Mary’, and refers to Mary, mother of Jesus.

So, was the chapel the location of a vision of Mary?

Extensive wear on the limestone floor seems to have been caused by large numbers of people visiting the building. We consequently assume that this was a very important place. Indeed, we may be looking at a site of pilgrimage.

Marian apparitions, supernatural appearances by Mary, and their commemoration in the form of shrines and chapels are still common across Catholic Europe. For example, in medieval Spain there are about a dozen well-documented accounts of apparitions of Mary, together with the pilgrimages and devotions they inspired.

Marian apparitions, supernatural appearances by Mary, and their commemoration in the form of shrines and chapels are still common across Catholic Europe. For example, in medieval Spain there are about a dozen well-documented accounts of apparitions of Mary, together with the pilgrimages and devotions they inspired.

At one time, abbeys, priories, churches, and chapels, associated with a religious apparition, were a feature of the English landscape. These include Thetford and Walsingham in Norfolk, and Aylesford in Kent. One story from the beginning of the eighth century is of the Virgin appearing to a swineherd named Eoves at what was to become Evesham. She told him to bring Egwin, Bishop of Worcester, there and to establish a church in her honour.

These kinds of apparitions are rooted in local traditions and stand at the interface between doctrinal Christianity and the beliefs in the supernatural world held by common people. Accordingly, the St Michael’s site may well have already had a place in folklore and have been of pre-Christian or ‘Pagan’ significance.

Other recorded sightings of Mary, Jesus and other saints often identify the person experiencing a vision. They describe someone located in the liminal or marginal position between society and nature, usually a herder of animals at the edge of the village. But then the apparition needs to be accepted as reliable to receive the approval of the church hierarchy; in this instance, the abbots of Torre Abbey. The Roman Catholic Church was very effective at integrating the popular and official in religious devotion.

Other recorded sightings of Mary, Jesus and other saints often identify the person experiencing a vision. They describe someone located in the liminal or marginal position between society and nature, usually a herder of animals at the edge of the village. But then the apparition needs to be accepted as reliable to receive the approval of the church hierarchy; in this instance, the abbots of Torre Abbey. The Roman Catholic Church was very effective at integrating the popular and official in religious devotion.

Torquay’s chapel was therefore one of many, perhaps a famous place of pilgrimage. Then it seems quickly to have been forgotten with even its name being changed.

This could have been a deliberate act.

Between 1536 and 1540, on the orders of Henry VIII, every abbey and priory in England, some 800 in total, was forcibly closed. As many as 14,000 monks, abbots, nuns and friars, as well as great numbers of monastic servants and tenants, had their lives disrupted. Two-hundred people were executed for opposing what became known as the Dissolution of the Monasteries.

Between 1536 and 1540, on the orders of Henry VIII, every abbey and priory in England, some 800 in total, was forcibly closed. As many as 14,000 monks, abbots, nuns and friars, as well as great numbers of monastic servants and tenants, had their lives disrupted. Two-hundred people were executed for opposing what became known as the Dissolution of the Monasteries.

Torre Abbey was of particular interest to Henry’s commissioners. By 1536 the Abbey’s annual income made it the wealthiest of all the Premonstratensian houses in England. The canons surrendered in 1539 and that same year a 21-year lease of the site and demesne was acquired by Sir Hugh Pollard. The Dissolution resulted in a widescale demolition of the church and east range, and all items of value, including the lead from the roofs, were seized. The south and west ranges mostly survived and were converted into a house for Thomas Ridgeway in 1598.

The closing of the Abbey was only part of the English Reformation. Following the accession of Edward VI, royal injunctions in 1548 ordered the removal of all images from English churches. Such iconoclasm caused the loss of baptismal fonts, stained-glass windows, depictions on walls, and crosses depicting the crucifixion known as roods.

The closing of the Abbey was only part of the English Reformation. Following the accession of Edward VI, royal injunctions in 1548 ordered the removal of all images from English churches. Such iconoclasm caused the loss of baptismal fonts, stained-glass windows, depictions on walls, and crosses depicting the crucifixion known as roods.

There was violent resistance to the changes. When the Act of Uniformity replaced the Latin liturgy with Archbishop Cranmer’s ‘Book of Common Prayer’ in 1549 it led to widespread unrest. The peasants of Cornwall and Devon rebelled, and a volunteer army marched eastward, capturing castles, destroying enclosures and laying siege to Exeter. Using foreign mercenaries, this Prayer Book revolt was crushed, and 5,000 poorly armed rebels were slaughtered. We aren’t aware if Torbay was represented in the rebel dead, but it is very possible that they were. Local folk would have at least sympathised with the rebellion.

There was violent resistance to the changes. When the Act of Uniformity replaced the Latin liturgy with Archbishop Cranmer’s ‘Book of Common Prayer’ in 1549 it led to widespread unrest. The peasants of Cornwall and Devon rebelled, and a volunteer army marched eastward, capturing castles, destroying enclosures and laying siege to Exeter. Using foreign mercenaries, this Prayer Book revolt was crushed, and 5,000 poorly armed rebels were slaughtered. We aren’t aware if Torbay was represented in the rebel dead, but it is very possible that they were. Local folk would have at least sympathised with the rebellion.

The 1530s and 1540s led to the near elimination of traditional devotion, including the closing of many chapels and the ending of pilgrimages and penance. Some chapels were symbolically removed. In 1170 the Archbishop of Canterbury Thomas à Becket was murdered by followers of Henry II in Canterbury Cathedral. Soon after his death, Becket was canonised by the Pope and his shrine became one of the richest in Europe. in 1538 Henry VIII had the shrine destroyed and a royal proclamation ordered that all memory of him should be removed from the English Church.

The 1530s and 1540s led to the near elimination of traditional devotion, including the closing of many chapels and the ending of pilgrimages and penance. Some chapels were symbolically removed. In 1170 the Archbishop of Canterbury Thomas à Becket was murdered by followers of Henry II in Canterbury Cathedral. Soon after his death, Becket was canonised by the Pope and his shrine became one of the richest in Europe. in 1538 Henry VIII had the shrine destroyed and a royal proclamation ordered that all memory of him should be removed from the English Church.

A particular target of the Reformation was devotion to Mary. From the late thirteenth century every church was required to have a statue of the Virgin. But Protestants saw the Catholic veneration of the Virgin to be a kind of adoration, turning her into a goddess thereby undermining the unique divinity of God. In consequence, all references to ‘Our Lady’ were purged from the English liturgy.

This was likely the reason why Torquay’s chapel was renamed and progressively removed, with all it stood for, from community memory.

This was likely the reason why Torquay’s chapel was renamed and progressively removed, with all it stood for, from community memory.

Devotion to Mary nevertheless survived. Some statues were hidden, such as Our Lady of Buckfast, while obscure pilgrim sites still attracted recusant Catholics. In some places remnants of what had once been standard practice remained, often in a confused form.

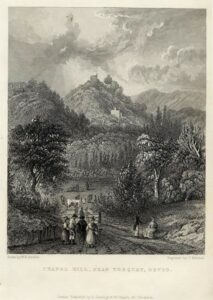

This seems to be the case in Torquay. A 1793 guidebook describes, “The Tor Chapel, perched on the summit of the ridge of rocks, once an appendage of the abbey before us and as it has not been desecrated it is sometimes visited by Roman Catholic crews of the ships lying in the bay.”

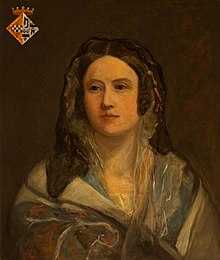

Seemingly acknowledging the importance of the Chapel in a long tradition, the Catholic philanthropist Sophia Crichton-Stuart, Marchioness of Bute (1809-1859), had a cross placed on its roof in the early nineteenth century.

Seemingly acknowledging the importance of the Chapel in a long tradition, the Catholic philanthropist Sophia Crichton-Stuart, Marchioness of Bute (1809-1859), had a cross placed on its roof in the early nineteenth century.

By that time the chapel had been renamed after the saint of high places. All over Britain, Ireland and Brittany, there are locations named after St Michael, including St. Michael’s Mount, Mont St. Michel, Skellig Michael, and the church on Glastonbury Tor. These are often on hills. Others, such as the Torquay chapel, are by the sea, over which Michael was said to carry the souls of the dead safely to Heaven.

‘Torquay: A Social History’ by local author Kevin Dixon is available for £10 from Artizan Gallery, Lucius Street, Torquay, or:

https://www.art-hub.co.uk/product-page/torquay-a-social-history-by-kevin-dixon