When we think of a Torquay stream the usual contenders are the Shire Brook which feeds into the King’s Pond and, of course, the River Fleet, marked by Fleet Street which flows to the west side of the harbour.

The Fleet has its place in Torquay’s history as a source of drinking water crucial to the town’s development; the conduit for cholera outbreaks in 1832 and 1849; and the borderland between the Carys and the Palks.

However, alongside the Fleet was another stream that found its way to the Strand (from the Old English ‘strond’, or seashore).

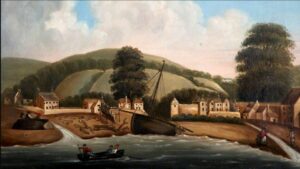

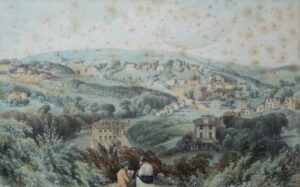

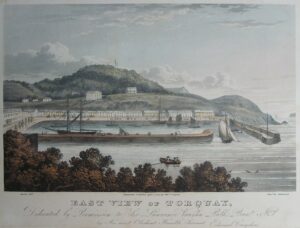

This stream was of less consequence than the Fleet and was smaller, though it can be seen in paintings from the eighteenth century as it empties into the harbour. By 1770, the area around the harbour, with its five inns, was known variously as Tor Kay, Torquay or Flete and the stream flowed through the narrow floor of the steep-sided Torwood valley. Early nineteenth century prints hint at a stream along a line of trees in that valley.

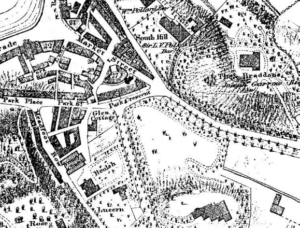

As the town grew, the stream was culverted at the waterside in the first decade of the nineteenth century. Early nineteenth century prints show the bottom of the original Market Street heavily built up which confirms this. However, John Wood’s 1841 Survey may suggest that the stream was still above ground as it progressed through Torwood Gardens. Originally a private purpose-built park by 1850, Torquay’s Local Board took possession of the gardens for the free benefit of all in 1853.

However, we do know of the stream’s probable source. Russell states that this is ‘Our Lady’s Well’. The well is remembered in Lydwell Rd off Windsor Road.

So this could suggest a holy well or spring. These were venerated as sacred sites both for pre-Christian religions and as Christian sites from as early as the 6th century.

The cult of holy wells continued throughout the medieval period, though its condemnation at the time of the Reformation (1540) ended new foundations. Nevertheless, folk customs at existing holy wells often continued, including pre-Christian customs such as folk healing and the capacity to affect a desired outcome for future events. Rituals often evolved, such as the donation of an object or coin to retain the ‘sympathy’ of the well for the person seeking its benefits. Hence, wishing wells. Structural additions included lined well shafts or conduit heads, often with a tank to gather the water at the surface; or even a roof. Across the country there are at least 600 survivors. The most notable local surviving holy well is in Totnes (pictured above).

At first glance, it appears as if the name of Wellswood could refer to where the well actually was. However, a lease of 1659 granted to John Black records, “closes, fields or pieces of ground, that is to say, one called Middle Hill, one close called Kent’s Hole, one close called Engden, one close called Wildeswood, one close called Old Close, and the meadow called Bramble Meadow.” Accordingly, Wellswood was probably originally ‘the wild wood’.

Wellswood covers much of the south-facing slope of Warberry Hill, the highest point within urban Torquay. This favourable aspect, though lacking direct sea views, provided perfect opportunities for the building of detached villas in spacious grounds – all needed water.

Indeed, it looks like the stream has been plundered for centuries. Russell comments that there was “a well-head built of stone at the Torwood Manor house”- Thomas Ridgeway completed Torwood Manor in 1579 as the family seat.

Unsurprisingly then, the actual name of the stream doesn’t seem to be on any map and may have been lost. Yet, there is a suggestion that it could be the Lyd. Russell notes that the Wellswood spring was also known as Lyd Well. ‘Hlid’ is Anglo-Saxon meaning a cover – and where we get lid. In other similar watercourses this refers to a stream being almost unnoticeable.

And so, nothing much to being with, victim to avaricious households, gardeners and town planners, by the time Victorian map-makers reached Torquay the Lyd could have been of such a reduced flow that it was hardly noticeable. There was very little left to actually reach the harbour, and so Torquay’s’ other stream vanished from our collective memory.