It was once believed that another a race of beings lived alongside humans in Torbay – a little people who have mostly long gone, either extinct or have been forced far away to Dartmoor, shrunk in size, learned to evade our gaze, or hidden below ground. We still remember them, however, in our dreams, or we have rendered them harmless and as figures of fun.

If they are still out there, they fled far from the reach of steam trains and gas lamps, but their presence can still be glimpsed in stories passed orally from generation to generation dating back hundreds or even thousands of years.

First of all, the setting. Medieval and early modern Torbay was a collection of rural communities, consisting of small populations with a variety of folk beliefs coexisting with an understanding of Christianity. And the night was often seen as an unfriendly place haunted by non-human entities, a living universe teeming with spirits, some malevolent and some willing to help.

Out there in the dark and in the hills was this enduring myth of the Pixie. Though narratives of our little people are now concentrated in the high moors of Devon and Cornwall, before the mid-nineteenth century, both Pixies and Fairies were taken very seriously with books on peasant beliefs featuring many incidents and sightings. Incidentally, the earliest published version of ‘The Three little Pigs’ story is from Dartmoor in 1853, but has three little Pixies in place of the pigs.

Places were named after them, such as Chudleigh’s Pixie’s Cave. According to John Britton’s ‘The Beauties of England and Wales’ (1803), the caves are said, “In the traditions of the peasantry to be inhabited by Pixies, or Pisgies, a race of supernatural beings, invisibly small”.

There were numerous local tales of mysterious, magical ‘little people’ living in the woods who would kidnap babies, cause misfortunes by casting spells, prevent cows from giving milk, chickens from laying eggs, and infertility in couples . Even in our Bay, some very local stories lingered, such as that of a dog lost in Kent’s Cavern finally emerging having lost all his fur to the grasping hands of those subterranean dwellers.

Indeed, we needed protection from these often malevolent creatures. As it was believed that these primitive people feared the metal weapons of their more sophisticated human enemies, to prove our technological superiority, we hung iron implements such as horseshoes over our front doors.

But were Pixies just a figment of our imagination, or could they be a half-remembered glimpse of a lost people?

Intriguingly, there was a migration into Britain around 4,400 years ago. The DNA data suggests that over a span of several hundred years, these new arrivals from continental Europe led to an almost complete replacement of Britain’s earlier inhabitants – the Neolithic communities who were responsible for megalithic monuments such as the Churston Chamber Tomb.

Welsh author and mystic Arthur Machen (pictured above) wrote of, “small dark aborigines who hid from the invading Celt”. There are even echoes of the presence of otherworldly beings thousands of miles away from Devon. For instance, the American horror writer HP Lovecraft’s family came from Newton Abbot, and it has been suggested that he imbibed some of his ideas from his Devonian forebears. He wrote of, “buzzing voices in imitation of human speech which made surprising offers to lone travellers on roads and cart paths in the deep woods.” HP Lovecraft is pictured below.

The DNA also shows that these incoming Beaker folk were physically different to the population they replaced, who had olive-brown skin, dark hair and brown eyes. In comparison, the Beaker folk brought lighter skin, blue eyes and blonde hair.

One theory is that our supernatural folk evolved from memories of this lost prehistoric race. For instance, that tradition of iron as a charm against Pixies could be a cultural memory of invaders with iron weapons displacing a people who had just stone and wood. Also, in folklore, Palaeolithic flint arrowheads were attributed as ‘elfshot’, while the little people’s green clothing and underground homes spoke of a need for camouflage and covert shelter from the persecution of newcomers.

But why were Devon and Cornwall the areas where belief in Pixies survived the longest?

One suggestion is that the far South West remained ‘Celtic’ for much longer than other parts of England – and we still retain a Celtic presence in our DNA. But fall we did as a consequence of the ‘Völkerwanderung’, the migration of Germanic and Slavic peoples into Europe from the 2nd to the 11th centuries – Devon’s part in this being the invasion of Anglo Saxons that replaced the original Celtic Dumnoni tribe in the Bay.

It may then be significant that Pixies and Fairies were never considered to be the same species by our ancestors. Pixies have a Celtic root while Elves and Fairies are later and are Anglo Saxon.

The invading Anglo Saxons had brought their own tradition. They believed in Elves and feared them as they could steal children and maliciously afflict humans and animals with physical ailments. Elves later took on the name of Fairies, a term which came to Britain from France in the later Middle Ages. Fairies could appear and vanish at will and lived underground in a parallel, royal and aristocratic society, with portals into our world in places such as lakes, woods, hills or prehistoric monuments.

Did the hierarchical world of the Fairies reflect that of the encroaching Anglo Saxon royal households?

Following the idea that Fairies have a place in Anglo Saxon culture, and Pixies are Celtic, it’s worth noting that Paignton is derived from an Anglo-Saxon personal name, while Brixham comes from Brioc’s farm, a Brythonic Celtic personal name. So, if Paignton is originally Anglo-Saxon and Brixham originally Celtic, does this mean that Paignton believed in Fairies and Brixham in Pixies?

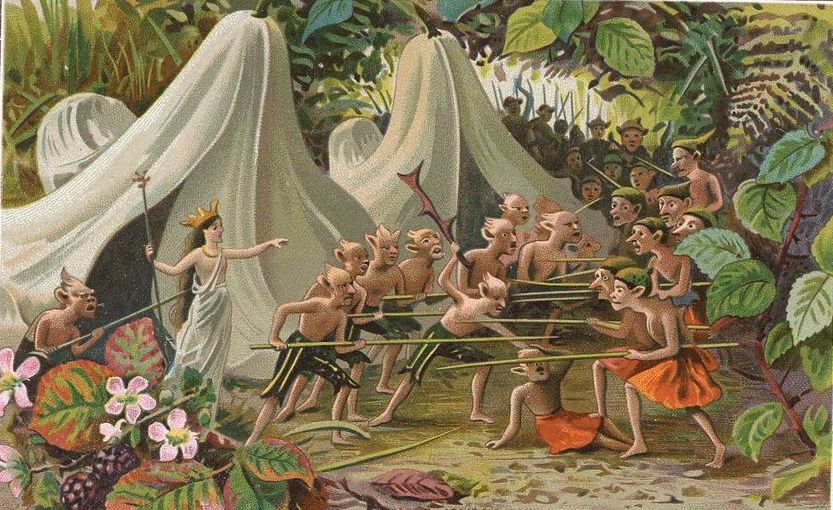

So Pixies and Fairies are not the same. Notably there is a tradition of enmity or even war between the two races. One story tells, “Of a time when the fairies who dwelt in Somerset and the lands to the east of the River Parrett wanted to cross the border and enter Devon to settle and extend their territory. However, the Devonian pixies, which already lived there, refused them entry. Soon war began between the two beings, and it violently and terribly raged across the landscape.” Above is a Victorian illustration of the Pixie-Fairy War.

Is this also a hint of a proxy conflict fought between the original and new inhabitants of Devon?

So, do our stories of a lost folk recognise our guilt at their extermination, in the case of the builders of the megaliths, or the absorption of the Celtic Dumnonii?

During the nineteenth century Torbay saw itself as modern and dismissed such stories of a lost or hidden race as rural superstitions to be treated with contempt, while church men saw Pixies as relics of Catholicism not fitting in with Biblical truths.

Also, over the centuries, Pixies became confused with other supernatural traditions. For example, the Brothers Grimm’s ‘Snow White’ story of 1812 was based on a much older tradition – Gnomes were first described during the Renaissance by Swiss alchemist Paracelsus as, “diminutive figures two spans in height who did not like to mix with humans”.

And so the Pixie was relegated to the status of a garden ornament, and the mischief-making relic of Torbay’s rich supernatural past is long gone… or perhaps not.

In 1922 the Torquay spiritualist Violet Tweedale (pictured below) gives us one of our few modern sightings of a Torbay Pixie.

She wrote, “One summer afternoon I was walking alone along the avenue of Lupton House. A few yards in front of me a leaf was swinging and bending energetically, while the rest of the plant was motionless. What was my delight to see a tiny green man. He was about five inches long, and was swinging back-downwards. His tiny green feet, which appeared to be green-booted, were crossed over the leaf, and his hands, raised behind his head, also held the blade. I had a vision of a merry little face and something red in the form of a cap on the head. For a full minute he remained in view, swinging on the leaf. Then he vanished.”

You can join us on our social media pages, follow us on Facebook or Twitter and keep up to date with whats going on in South Devon.

Got a news story, blog or press release that you’d like to share or want to advertise with us? Contact us