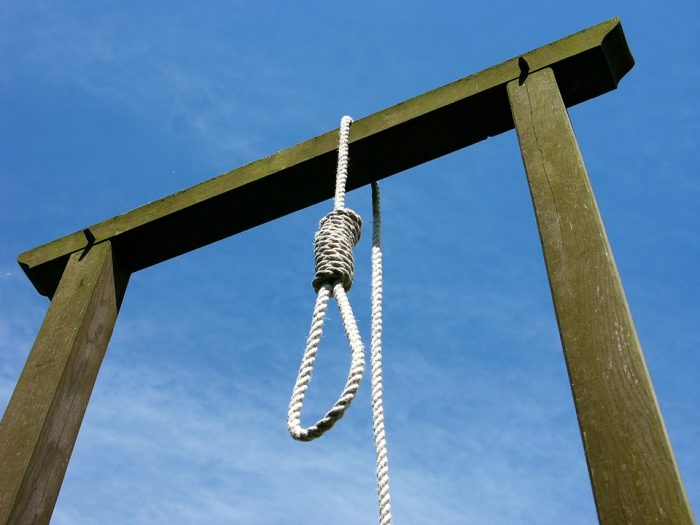

We’ve mentioned before that Torquay’s site for public executions was Gallows Gate.

Our town’s place of terminal justice is just by the roundabout at the top of Hamelin Way on the A380. At around 495 feet above sea level, the site is on an ancient ridge way and where the four parishes of Cockington, Marldon, Kingskerswell, and St Marychurch meet.

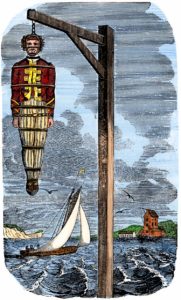

It was, of course, where we hanged folk for probably over a thousand years. What is less recognised is that it was also the site of a gibbet. Gibbeting was the practice of locking criminals in human-shaped cages and hanging them up for display in public places. It was also called ‘hanging in chains’. The gibbet itself refers the wooden structure from which the cage was hung.

In most cases, criminals were executed prior to being gibbeted. However, some were occasionally gibbeted alive and left to die of exposure and starvation. There’s a bit of a gender bias in this, as it only applied to men- female criminals were always dissected rather than gibbeted.

Although gibbeting was known in medieval England, the height of its popularity in England was in the 1740s. Gibbeting became common then due to a perceived increase in murders, and was regularised in England by the Murder Act of 1752. This stipulated that “in no case whatsoever shall the body of any murderer be suffered to be buried”, the cadaver was either to be publicly dissected or left “hanging in chains”.

It was believed that the best way to stop crime was making punishment as appalling as possible. Authorities saw gibbeting as a way to prevent not only murder but also lesser crimes such as robbing the mail, piracy, and smuggling.This was a time when Christians believed in bodily resurrection, so the idea that after their death their body would be cut up or eaten by carrion crows was horrifying and added an extra punishment.

This was one reason why Gallows Gate is a long way from our villages- living near a gibbet was very unpleasant as the corpses were often left there for years. The authorities also made gibbeted bodies difficult to remove by hanging them high, sometimes from 30-foot posts.

Another reason for making the executed difficult to access was that the criminal corpse was believed to possess curative powers. The practice, most commonly known as ‘stroking’, involved placing the right hand of an executed criminal on an afflicted area of the body. Even into the late eighteenth century there are numerous reports of people whittling splints off gibbet posts to cure ailments such as toothache. The last use of stroking was recorded as late as 1863.

As a metal frame was needed it was also expensive, and so reserved for those most likely to make an impression. Unlike wooden gallows which rotted, over a dozen gibbet cages consequently survive, most of which are in small museums. As a further reminder, many criminals lent their names to the places where they were gibbeted. As a result, many towns and regions have roads and features that bear the names of gibbeted criminals.

A visiting Frenchman observed, “After hanging murderers are punished in a particular fashion. They are first hung on the common gibbet, their bodies are then covered with tallow and fat substances, over this is placed a tarred shirt fastened down with iron bands, and the bodies are hung with chains to the gibbet and there it hangs till it falls to dust. This is what is called in this country to hang in chains.”

The practice ended in 1832 and was formally abolished in 1834, though it took a few decades before the last gibbet was removed.