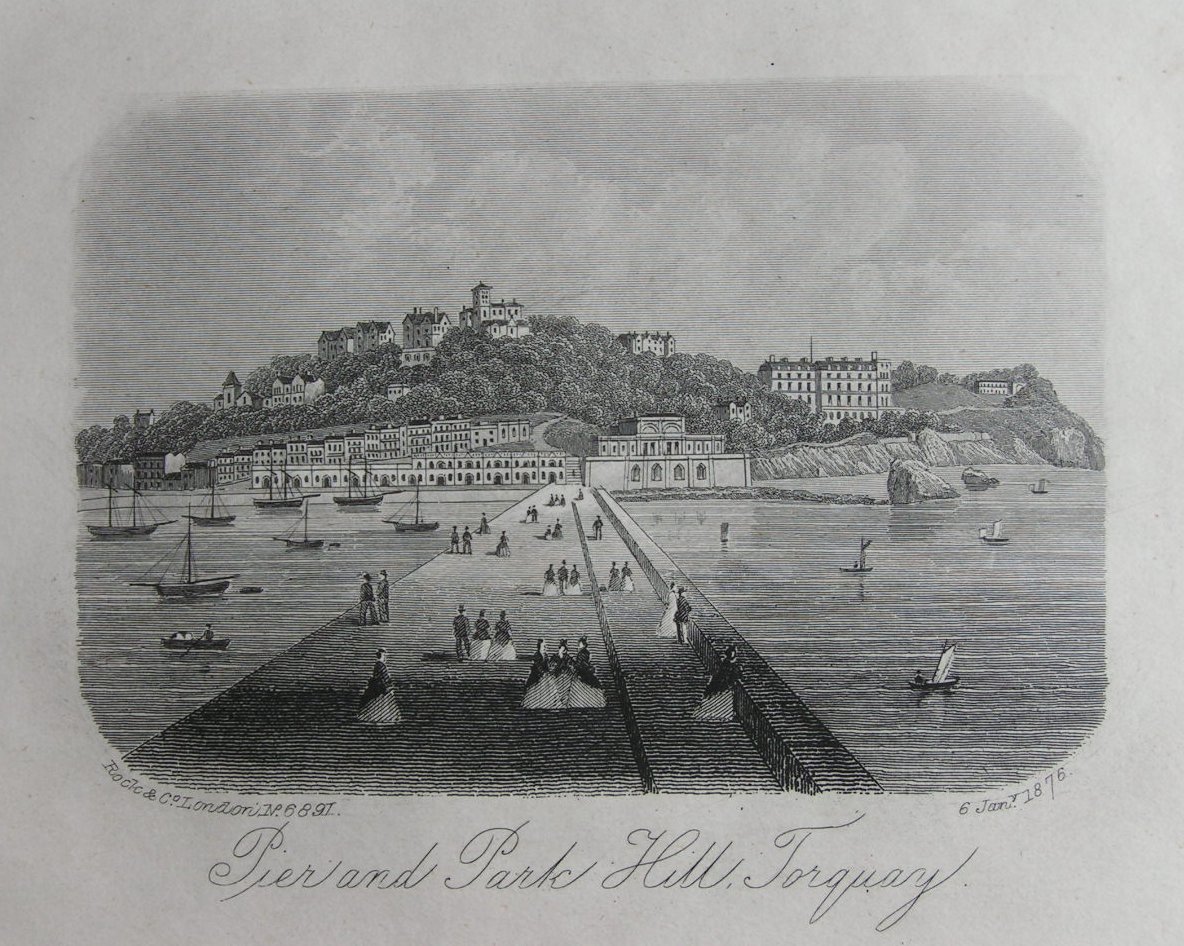

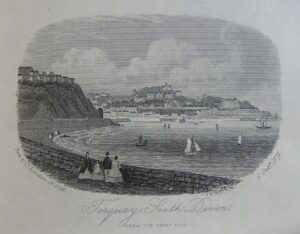

If we look at images from Victorian Torquay, it’s noticeable that everyone wore a hat.

And for much of the century men wore a specific hat, for all occasions, at any time of day. This was the top hat, the symbol of the nineteenth-century masculine Empire-builder and gentleman at leisure in the seaside resort for the nation’s elite.

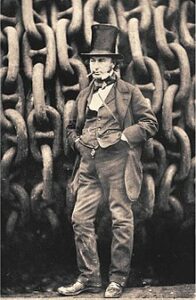

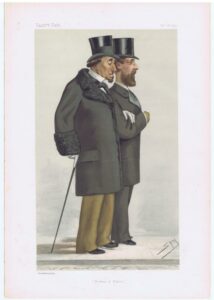

Giving just two examples from politics and industry, pictured are Torquay visitors Disraeli and Brunel.

The top hat emerged by the end of the eighteenth century, replacing the tricorne that can be seen in many illustrations of Torquay. It may have descended from the sugarloaf hat, which was named after the loaves into which sugar was formed at that time – and, incidentally, remembered in the shape of Sugarloaf Hill in Goodrington.

The first silk top hat in England is credited to Middlesex hatter George Dunnage in 1793. Within 30 years top hats had b

ecome popular with all social classes, even workmen wore them despite their apparant impracticality. It seemed to particularly appeal to the Romantic Movement which had established a style in literature and art, emphasising the senses and emotions. Clothing was part of that flamboyance and top hat designs reflect this.

For a few decades hats made of beaver fur were popular because of its water proof properties. Black silk then became the standard, sometimes varied with grey top hats. When dress coats as conventional formal daywear were replaced by the frock coat from the 1840s, top hats continued to be worn, but it wasn’t until 1850 that the fashion really took off when Prince Albert starting wearing the striking headgear in public. The top hat then inevitably became a focus for the stylish male and remained so for the next fifty years.

Men wore top hats for business, pleasure and formal occasions. The hat came to proclaim the spirit of the age, with some writers even noting how an assemblage resembled factory chimneys, so contributing to the mood of the industrial era.

This was a symbol of urban respectability. It represented status, wealth, elegance, and formality. It made a statement, was a symbol of business and considered ‘the’ hat for the bourgeois man. The top hat made its wearer feel taller, self-assured and suave, particularly when tilted at a 10 degree angle.

Dramatic, and imposing, there was also a psychological impact as it could intimidate. It was described at the time as “a tall structure having a shiny lustre and calculated to frighten timid people.” Accordingly, top hats became part of the uniforms worn by policemen and postmen to give them the appearance of authority.

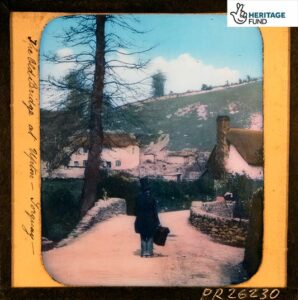

The image of the old bridge at Upton is from Torquay Museum’s collection

The height and shape varied through the century as minor modifications came and went out of fashion, their individual names coming from their shape, height, or size. The 1840s and the 1850s saw the top hat reach its most extreme form, with ever-higher crowns and narrow brims; the stovepipe being the most notable.

As a matter of course, such an important symbol attracted conventions and rituals. Etiquette demanded that the hat remained on outdoors. Indeed, a man outdoors without a hat would be a subject of negative comment. An exception would be orators who would remove their hats while speaking, so that the audience might observe their facial expressions.

Once indoors, the rule became less clear and depended on whether this was a public or a private space. In Torre and Torquay railway stations, Union Street shops, hotel lobbies, public houses, and dance halls, the hat usually remained on. In more respectable spaces, such as a harbour side restaurant, hats would be removed and there would be pegs upon which they could be hung.

In the Royal Theatre and Opera House in Abbey Road the hat would be removed once the gentleman took his seat. This would be out of consideration for those sitting behind. It would then be checked along with the topcoat in the cloakroom. For some, however, this would have been less necessary as the Frenchman Antoine Gibus had invented a collapsible ‘opera hat’ in 1823.

When entering a home the hat was generally removed immediately and given to a servant. In a brief visit, the hat would be removed, but retained in the hand.

With all this hat wearing, and the taking off and putting on, ‘hat hair’ was avoided by the widespread use of hair oil.

This was, of course, predominantly a male fashion; women had their own millinery with its discrete messages. On the other hand, women’s riding clothes did include a top hat with an attached veil, as we can see from this image of a female rider on the ‘Paignton Road’.

Essentially, the top hat was a nineteenth century institution and by 1900 was only being worn for special occasions such as weddings and dances. However, there was a short-lived resurgence in the 1930s when movie stars Fred Astaire, Gary Cooper, Marlene Dietrich and others, brought it back in favour.

Yet, the inter-war period saw the widespread introduction of informal suits. These were worn with less overbearing hats such as bowlers, homburgs, boaters and fedoras. Accordingly, after World War II, white tie, morning dress and frock coats, along with their counterpart, the top hat, were largely confined to high society, politics, and international diplomacy.

Today you are only likely to see a top hat at weddings and televised horse racing. Or perhaps in the theatre. In 1914, the Parisian magician, Louis Comte, debuted his new trick of pulling a white rabbit from the depths of his top hat.