This is the story of the ‘Torquay War’ of 1888.

During that year Torquay experienced a sustained challenge to established authority which became an important issue for the entire country.

This struggle was around a deeply symbolic principle of public assembly and followed the arrival of the Salvation Army. The town had become a focus for Salvationist activity due to a newly imposed prohibition of musical processions on Sundays.

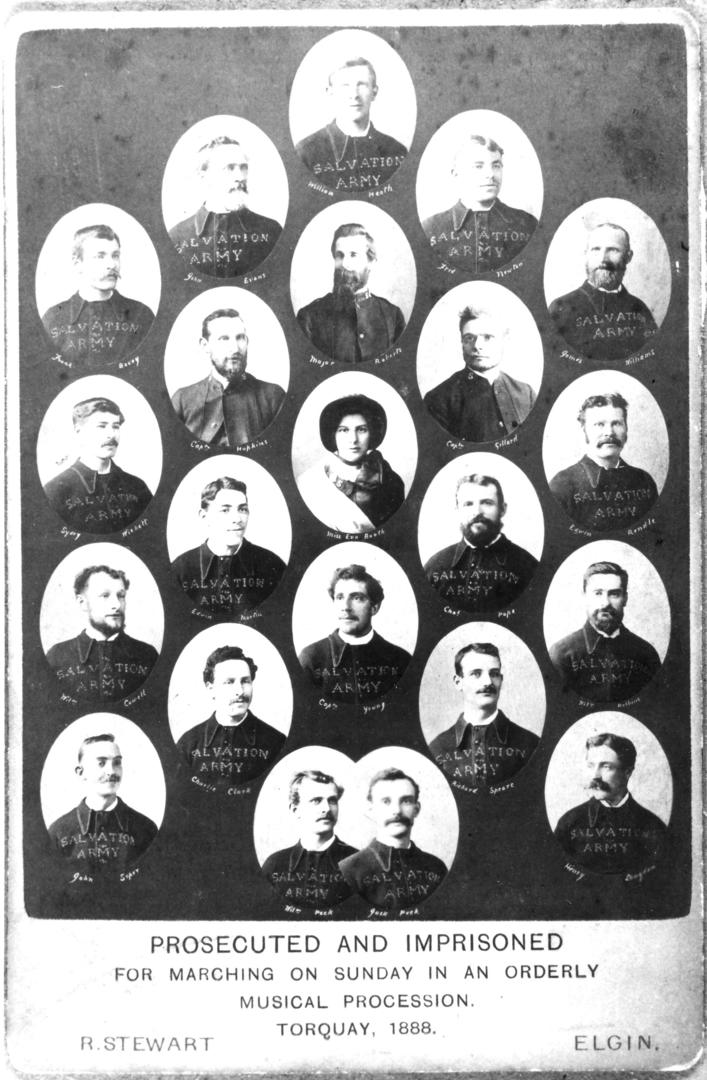

In January 1888 Torquay’s police charged a Salvation Army band with infringing these regulations. The Corps Commander, the bandmaster and several bandsmen were fined, but refused to pay and were subsequently jailed.

Refusing to cease their Sunday parades, on February 3 eleven more were summonsed for the same offence. A pattern then emerged with the bandsmen playing every Sunday, being summonsed, and often jailed. A regular event was the musical procession that accompanied prisoners being taken to Exeter prison and to welcome them on their return.

Over a hundred were eventually prosecuted and imprisoned and, over the months, the Army was reinforced by bandsmen from Exeter, Newton Abbot, Crediton, Barnstaple and Ilfracombe. In a cat-and-mouse game, the police responded with surveillance, infiltration, intimidation, and, according to reports, the occasional violent assault. Meanwhile, taking advantage of the confusion, young men engaged in “rowdyism and riot”.

William and Catherine Booth’s 23 year-old daughter, the irrepressible Evangeline Cory Booth (pictured), was sent to coordinate the campaign from the Army’s ‘Fort’ in Temperance Street. She pronounced, “The majority in the world are sinners, and are quite against goodness, and I’m afraid it’s the same in Torquay.”

The opposition to her presence would become vitriolic. One Torquay hotel proprietor was quoted as offering, “Ten pounds to the man who will quiet her.”

Though out of Torquay’s population of 25,000 only 229 were Salvationists, the bands’ illicit appearances attracted thousands of sympathisers who were prepared to defend the Army as it marched. To give an idea of the nature of the increasingly acrimonious conflict, here is a selection of reports of the weekly events:

“A great crowd gathered at Market Street, waiting for the prisoners to be taken to the railway station. The Royal Hotel bus was hired, and the prisoners were placed in it in charge of four constables. The progress of the vehicle was greatly obstructed while proceeding down Market Street, and on turning the corner it was nearly overturned…

“The confusion was so great that many people, including two constables were thrown to the ground, and the bus passed over the leg of PC Cole…

“At Market Corner, a posse of police marching as if for duty broke into units and, led by a sergeant, fell foul of the procession…

“The band marched ahead and reached the Fort. The other Salvationists were included in a riot, some of the ‘lassies’ losing their tambourines…

“With considerable tenacity the women held on to the flag…

“A cab man tried to lash his horse through the Salvationists and blows were exchanged…”

The national Press took an interest to what was happening as the resort claimed to be the richest town in England. Who won would set a precedent across the nation.

The ‘Torquay War’ carried on for six months before the Salvationists won their campaign and the law was changed.

While some see the whole episode as simply an insignificant case of the principled falling foul of local edicts, note the following from ‘The War Cry’ of 1888:

“The class at Torquay amid which, and for which, the Salvation Army works, seems to have grasped that it is fighting the battle of the masses… on the other side are ranged the local ‘society’ – black-hatted respectability, practical Toryism, the Army’s ‘betters’ generally – everything that cries ‘hush’ when one asks for a law to prevent wrong.”

Booth’s Army represented a challenge to public order and the power and position of Torquay’s social and political elite. Concern amongst the Anglican churches was also growing over the rise of non conformist traditions which were attracting working class members with new forms of worship and often egalitarian ideas.

Many were wary of anyone organising the poor into a movement, let alone an ‘Army’, and the Salvationists openly proclaimed that they were the friend of the ‘dangerous classes’, their first converts being alcoholics, morphine addicts, prostitutes and others unwelcome in polite Christian society.

Their Foundation Deed further stated that women had the same rights to preach as men, another dangerous idea.

There was also the emphasis on abstinence in a town where so many businesses relied on selling alcohol. In one incident it was reported that, “Roughs brought in from the neighbourhood, and led by two policemen, attacked the band”.

This may suggest why the authorities’ reaction seemed so disproportionate, why compromise was so difficult, and why the Torquay War escalated.

That the Army won their campaign indicated that times were changing and that the control exercised by the town’s religious and secular elite was waning in a modernising Torquay.

You can join us on our social media pages, follow us on Facebook or Twitter and keep up to date with whats going on in South Devon.

You can join us on our social media pages, follow us on Facebook or Twitter and keep up to date with whats going on in South Devon. Got a news story, blog or press release that you’d like to share or want to advertise with us? Contact us