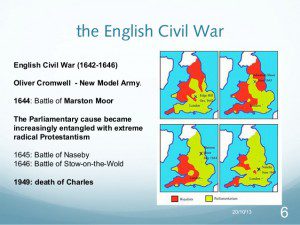

The English Civil Wars lasted between 1642 and 1651 and were fought between Parliamentarians (Roundheads) and Royalists (Cavaliers). The conflict was mainly over how the English were government, though Wales, Scotland and Ireland were also involved.

We don’t know much about the affiliations of the small fishing and farming communities of the Bay during the Civil Wars. However, across England fishing communities and large towns and cities (such as Exeter and Plymouth) generally supported Parliament while rural areas dominated by the aristocracy often supported the King. Accordingly, Brixham and Paignton may have tended to be sympathetic to the Parliamentary cause. It’s been suggested that this was partly due to the spread of Puritan ideas amongst seafarers who were away from the influence of landowning Royalists. Newton Abbot, on the other hand, is reported to have remained loyal to the King.

Our Bay villages were very small and weren’t seen as strategic goals by either side in the Wars. As they consequently don’t appear much in the historical record, we may need to look at similar communities that were directly affected.

One neighbouring example is that of Dartmouth. In July 1643 after Exeter fell to a Royalist advance, the King’s commander in the South West, Charles’ nephew Prince Maurice, (pictured below) moved south, first taking Totnes and then approaching Dartmouth. The Prince wrote, “It is difficult to imagine how it must have felt to have a Royalist army marching towards your little town. Although there was obviously fighting within some families, the majority supported Parliament and a course of action was soon decided upon.”

In late August Maurice offered generous terms if Dartmouth were to surrender, but this was refused even though the situation was clearly hopeless for the inhabitants. On October 4 1643 the Royalists attacked and quickly took the town. The battle claimed the lives of 17 Dartmouth men. Hence, as there were similarities between Dartmouth and the Bays’ fishing communities, we could assume a similar political outlook.

One piece of real evidence does exist. There is a letter written by the Prince Maurice to Colonel Edward Seymour who was then at Torre Abbey. He instructed him to deal with: “Diverse persons disaffected to His Majesty’s service and peace of the Kingdom do associate and meet together about Torbay in a hostile manner to the great terror and distraction of His Majesty’s loyal subjects… I authorise you, for the suppression of which insurrection to repair with your force to Torbay… there to repress and reform the same, and in the case of opposition or resistance to slay, kill and put to execution of death by all ways and means.”

We don’t know whether the Colonel acted on this instruction but it does seem to suggest some Parliamentary sympathies amongst those in the Bay. Seymour (1610-1688) was, of course, a Royalist. He was later to become Sir Edward Seymour, 3rd Baronet. In April 1640, he was elected MP for Devon in the Short Parliament and re-elected for the Long Parliament in November 1640. He was appointed a colonel in the Royalist army in 1642 and was disabled from sitting in Parliament in 1643. In the latter part of the Civil War he was imprisoned in Exeter and was not released until 1655. He inherited the baronetcy of Berry Pomeroy on the death of his father in 1659. After the Restoration of Charles II in 1660, Seymour became DeputyLieutenant for Devon and in 1661 was elected MP for Totnes in the Cavalier Parliament and sat until 1679. He was appointed Vice Admiral in 1677 and held the position until his death. He served as High Sherriff of Devon for 1679–80. He was re-elected MP for Totnes in 1685 and sat until his death.

Many portrayals of the Civil Wars on the big or small screens romanticise the conflict, and present a courteous struggle of honourable men on both sides. Yet, the Wars were devastating for the three nations involved. A religious aspect contributed to atrocities on both sides – Parliament passed a law, for example, that any Catholic soldier captured should be put to death. This was savage series of sieges (such as those at Exeter and Plymouth), skirmishes (at Heathfield) and major battles – a time of executions, pillage and massacre. As was usual in wars of this era, disease caused more deaths than combat.

There are no accurate figures for casualties but some attempt has been made to provide rough estimates. In England, a conservative estimate is that roughly 100,000 people died from war-related disease. Historical records count 84,830 dead from the wars themselves. Overall the estimate is of 190,000 dead, out of a total population of about five million. The wars were also fought in Scotland and Ireland. Overall, historians believe that England suffered a 3.7% loss of population, Scotland a loss of 6%, while Ireland suffered a massive loss of 41% of its population.

The outcome of the Wars was the trial and execution of Charles I; the exile of his son, Charles II; and the replacement of the English monarchy with, at first, the Commonwealth of England and (1649–53) and then the Protectorate (1653–59) under Oliver Cromwell’s personal rule. The monopoly of the Church of England on Christian worship in England ended. The Wars established the precedent that an English monarch cannot govern without Parliament’s consent. They also unleashed a wave of new ideas that, in the words of the song ‘The World Turned Upside Down’, linger on:

…