During the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, some commentators were referring to ‘men’s towns’. These had a conspicuous masculine presence in industry, such as mining or steel working, or in the military. They also referred, often dismissively, to places where women were in a visible majority and where they possessed a social and economic power base.

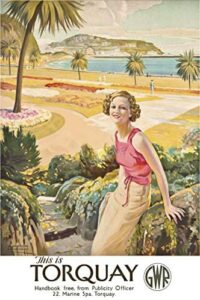

One such ‘woman’s town’ was Torquay.

Since the beginnings of Torquay as a town, there have always been far more women than men, particularly amongst the working-classes.

Since the beginnings of Torquay as a town, there have always been far more women than men, particularly amongst the working-classes.

For example, in 1881 England and Wales had a population of 25,974,439 with slightly more women than men; for every 100 males there were over 105 females. A similar preponderance of females existed in almost all European countries; only Greece and Bulgaria had males in the majority, with Belgium and Italy having an almost exact balance.

But Torquay was always very different.

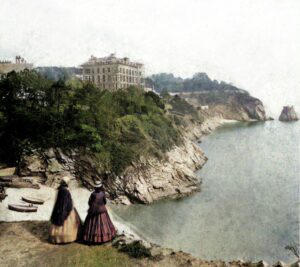

Our mythical seven hills boasted five hundred villas where the prosperous middle classes had escaped the noise and dirt of urban humanity. The affluent had come to live in quiet residential areas or to holiday in hotels and boarding houses. To service this new population was an unusually large servile class which the resort pulled in from its surrounding villages and from across the nation.

The nature of the tourism and service industries then saw women far outnumbering men. This was largely due to there being a tax on indoor male servants making men’s wages considerably higher, and that women were regarded as being more obedient.

The nature of the tourism and service industries then saw women far outnumbering men. This was largely due to there being a tax on indoor male servants making men’s wages considerably higher, and that women were regarded as being more obedient.

As a consequence, by 1881 Torquay had a population of 13,665 males but 19,293 females.

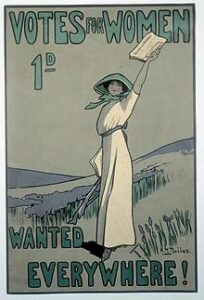

The town’s economy and culture then created other anomalies. The nineteenth century was an age of gender inequality with women and men inhabiting ‘separate spheres’. This idea was based on ‘natural’ characteristics with women considered physically weaker yet morally superior to men, meaning that women were best suited to the domestic arena and men to the public sphere. It was this that was often used as an argument against giving women the vote.

Women had few legal, social, or political rights They could not vote, could not sue or be sued, could not testify in court, had little control over personal property after marriage, if divorced would be unlikely to be granted legal custody of their children, and could not enter higher education.

To such a lack of power, there were, of course, exceptions amongst Torquay’s wealthiest women. Baroness Coutts being an obvious counterexample.

To such a lack of power, there were, of course, exceptions amongst Torquay’s wealthiest women. Baroness Coutts being an obvious counterexample.

Accordingly female occupational choices were limited with much available employment being exploitative and poorly paid. Yet, in the interstices of patriarchal, capitalist and Anglican Torquay, some women created spaces where they had power and agency. These included the pub landlady, the guest house owner, and the Spiritualist medium.

.In an untypical town, these women created a series of communities of mutual support. In doing so, they reinforced the liminal nature of the coastal resorts, places on the margin between sea and land, where class and gender were confused and inverted.

By the mid-nineteenth century Torquay already had 48 drinking establishments available for a population of 11,400. Many of the smaller establishments were operated by women while their husbands went out to work. This was the realm of the pub landlady.

By the mid-nineteenth century Torquay already had 48 drinking establishments available for a population of 11,400. Many of the smaller establishments were operated by women while their husbands went out to work. This was the realm of the pub landlady.

The role of guest house landlady had similarly evolved in parallel to the town. In 1850 there were only 150 hotel rooms available in Torquay, with a further 70 lodging housekeepers offering another 350 rooms. From the 1860s onward, to cater for this new demand, there was a rapid growth in hotel building for the well-off.

But beyond the large hotels, lodging was in private houses. These were independently owned and catered for the market by providing cheap, unpretentious accommodation. Notably, very few single men ran a guesthouse, the sector being clearly perceived as being a woman’s business.

As profit margins were tight, the home limited in space, and the family workforce often stretched, many landladies found it necessary to impose a strict discipline.

Hence their image as fierce and tight-fisted harridans, in contrast to their emasculated husbands. As with many stereotypes, there was some truth here, but also the male-female role reversal and the existence of a cadre of powerful women does seem to have caused genuine unease. The landlady consequently ended up as a great British comic institution, the focus of jokes and seaside postcards for decades. If we want a later example, we have Sybil Fawlty, a far more effective manager of Fawlty Towers than her husband.

Hence their image as fierce and tight-fisted harridans, in contrast to their emasculated husbands. As with many stereotypes, there was some truth here, but also the male-female role reversal and the existence of a cadre of powerful women does seem to have caused genuine unease. The landlady consequently ended up as a great British comic institution, the focus of jokes and seaside postcards for decades. If we want a later example, we have Sybil Fawlty, a far more effective manager of Fawlty Towers than her husband.

A further opportunity for women came with the growth in popularity of Spiritualism. Neither the Anglican nor Catholic traditions allowed for female leadership, but the practice of mediumship did, allowing a few women to achieve the status of local celebrities.

A further opportunity for women came with the growth in popularity of Spiritualism. Neither the Anglican nor Catholic traditions allowed for female leadership, but the practice of mediumship did, allowing a few women to achieve the status of local celebrities.

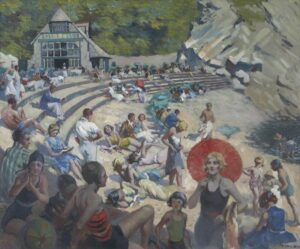

By the beginning of the twentieth century, Torquay was changing. The population was expanding, the middle class growing and there were new opportunities. By 1911 17,033 males and 21,738 females were resident in the town.

During the Great War men were sent off to fight and women entered traditional male employment. After the conflict many women did not return to their domestic service roles and there was more wok available in the more competitive hotel marketplace

During the Great War men were sent off to fight and women entered traditional male employment. After the conflict many women did not return to their domestic service roles and there was more wok available in the more competitive hotel marketplace

After war, pandemic, and economic decline, in 1921 the male population had fallen to 15,936; while the female population had increased to 23,495.

In 1939 the gap had widened significantly: 20,146 males to 32,081 females.

Even in 1961 there were 23,624 males to 30,422 females in Torquay.

Since then, the gap has narrowed but we still retain a slightly higher female population than the national average. The 2021 National Census shows that Torbay’s total population is 139,324, made up of 71,493 females and 67,831 males.

And so, after two-hundred years Torquay was again converging with the rest of Britain. Perhaps another indication that the town had moved away from its origins as a tourist resort to become more like other provincial conurbations.

‘Torquay: A Social History’ by local author Kevin Dixon is available for £10 from Artizan Gallery, Lucius Street, Torquay, or:

https://www.art-hub.co.uk/product-page/torquay-a-social-history-by-kevin-dixon