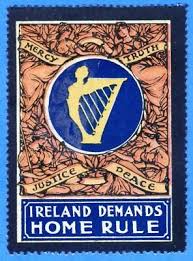

The journey towards an independent Ireland was long and troubled. The First Irish Home Rule Bill was introduced in 1886 and defeated in the House of Commons. The Second Irish Home Rule Bill of 1893, also backed by the British Liberal Party, was passed by the House of Commons, but vetoed in the House of Lords. A third Home Rule Bill was finally passed in 1912, though its implementation was delayed by the outbreak of the First World War.

However, Irish Independence was always going to be difficult. The North had the only large-scale industrialisation and was the most prosperous part of Ireland. It was also home to a large number of Protestants who supported continued union with Britain.

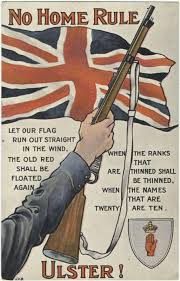

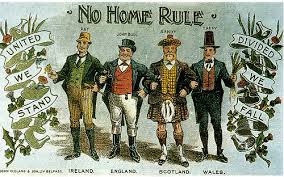

In the latter part of the 19th century, sectarian divisions in Ulster had formed two political camps. There were the unionists, who supported continued union with Britain and who were mostly, but not exclusively, Protestant. Ulster’s Protestants usually opposed Home Rule, fearing for their religious rights and calling it the “Rome Rule” of Catholic-dominated Ireland. There were also nationalists who wanted the repeal of the 1800 Act of Union and Home Rule for Ireland. They were usually, though not exclusively, Catholic.

In the latter part of the 19th century, sectarian divisions in Ulster had formed two political camps. There were the unionists, who supported continued union with Britain and who were mostly, but not exclusively, Protestant. Ulster’s Protestants usually opposed Home Rule, fearing for their religious rights and calling it the “Rome Rule” of Catholic-dominated Ireland. There were also nationalists who wanted the repeal of the 1800 Act of Union and Home Rule for Ireland. They were usually, though not exclusively, Catholic.

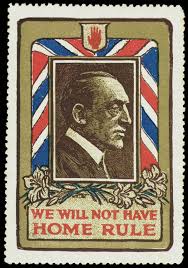

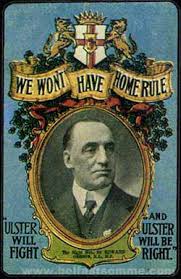

In 1912 thousands of unionists, led by the Dublin-born barrister Sir Edward Carson (1854-1935) signed the Ulster Covenant pledging to resist Home Rule. This movement also set up the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF). Carson’s ability to rouse crowds had as much resonance in Britain as in ‘Protestant Ulster’. Enormous crowds turned out to protest against Home Rule throughout Britain and not just in those cities such as Liverpool and Glasgow which were known to have sectarian divisions based on religion.

Far away in Torquay local people took sides and our newspapers were full of letters supporting either Home Rule or the Ulster Unionists. Often this division was along party lines: the pro-Home Rule Liberals; and the Conservatives and Unionists who, as the name suggests, wanted a continued union between Britain and Ireland. When the Ulster Covenant pledging to resist Home Rule was signed in 1912, from Torquay arrived a telegram that read: “Torquay Division Unionists send best wishes for your success.”

Far away in Torquay local people took sides and our newspapers were full of letters supporting either Home Rule or the Ulster Unionists. Often this division was along party lines: the pro-Home Rule Liberals; and the Conservatives and Unionists who, as the name suggests, wanted a continued union between Britain and Ireland. When the Ulster Covenant pledging to resist Home Rule was signed in 1912, from Torquay arrived a telegram that read: “Torquay Division Unionists send best wishes for your success.”

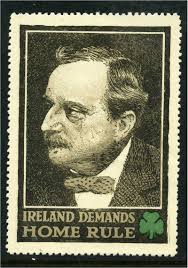

On December 9 1912 Sir Edward Carson (pictured left on the stamp) arrived in Torquay to speak from the balcony of the Conservative Club. He was barracked by a party of Torquay Liberals when he came to address a torchlight procession of Devon Unionists. Mocking the solemnity of the occasion, the Liberals arrived, “attired in helmets and carrying dummy rifles”. The Liberals held aloft banners labelled ‘King Carson’s Braves’ and ‘Carson’s Unionettes’ – a mocking reference to Torquay’s Suffragettes.

The pro-Unionist local paper called these, “disgraceful scenes in Union Street…” They described, “Gangs of hooligans… with banners and tin trumpets… in mockery of the Ulster day demonstration at Belfast”. The demonstrators, “howled Carson down” and he “gave up the attempt to speak.”

Northern Ireland was created as a division of the United Kingdom by the Government of Ireland Act 1920. Even after Irish Independence seemed inevitable Carson was convinced that Ireland would come home to the Empire.

Northern Ireland was created as a division of the United Kingdom by the Government of Ireland Act 1920. Even after Irish Independence seemed inevitable Carson was convinced that Ireland would come home to the Empire.

Indeed, Carson was back in Torquay on 30 January 1921. In his speech he said: “There is no one in the world who would be more pleased to see an absolute unity in Ireland than I would, and it could be purchased tomorrow, at what does not seem to me a very big price. If the South and West of Ireland came forward tomorrow to Ulster and said – ‘Look here, we have to run our old island, and we have to run her together, and we will give up all this everlasting teaching of hatred of England, and we will shake hands with you, and you and we together, within the Empire, doing our best for ourselves and the United Kingdom, and for all His Majesty’s Dominion will join together’, I will undertake that we would accept the handshake.”

The Irish Free State, comprising four-fifths of Ireland, was declared in 1921, ending a five-year Irish struggle for independence from Britain. Like other autonomous nations of the former British Empire, Ireland was to remain part of the British Commonwealth, symbolically subject to the king. The Irish Free State later severed ties with Britain and was renamed Eire, and is now called the Republic of Ireland.

The Irish Free State, comprising four-fifths of Ireland, was declared in 1921, ending a five-year Irish struggle for independence from Britain. Like other autonomous nations of the former British Empire, Ireland was to remain part of the British Commonwealth, symbolically subject to the king. The Irish Free State later severed ties with Britain and was renamed Eire, and is now called the Republic of Ireland.

For more community news and info, join us on Facebook: We Are South Devon or Twitter: @wearesouthdevon

…