In 1982 unemployment reached a peak of 3,070,621, representing 12.5 per cent of the working population. In some areas dominated by declining industries such as coal mining, it was much higher still.

As we still do, Torquay experienced high levels of joblessness at the time. In response, Torbay Trades Union Council set up the Torquay Unemployed Centre in 1981. The Centre was in the back office of the General & Municipal Boilermakers Union in Madepore Road, just off what locals still call the Post Office Roundabout. Run by unemployed volunteers, the Centre offered advice and support to anyone who came through the door.

In 1983 the centre was awarded funding by the Government’s Community Programme initiative and relocated to a derelict community centre in Factory Row.

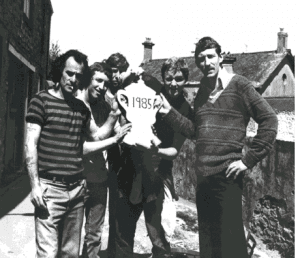

For the next three years the Centre’s 10 workers supported the town’s jobless, homeless and disadvantaged with advice, cheap food, furniture and friendship. It was often the first port of call for the many workless people who came to the Bay from the north of England, Scotland and Wales (both locals and incomers are pictured in these three images).

For the next three years the Centre’s 10 workers supported the town’s jobless, homeless and disadvantaged with advice, cheap food, furniture and friendship. It was often the first port of call for the many workless people who came to the Bay from the north of England, Scotland and Wales (both locals and incomers are pictured in these three images).

Rejecting the stereotype of the unemployed as passive recipients of welfare, Centre users campaigned against joblessness and worked together with other anti-poverty groups in the Cornwall and Devon Unemployment Resource Network and with the trades unions.

Rejecting the stereotype of the unemployed as passive recipients of welfare, Centre users campaigned against joblessness and worked together with other anti-poverty groups in the Cornwall and Devon Unemployment Resource Network and with the trades unions.

In 1981 it was decided that a great People’s March for Jobs would be held to draw attention to high unemployment. It began on 1 May 1981 in Liverpool at the Pier Head when 500 unemployed people began their 280 mile march to London. This was preceded by an ecumenical service in Liverpool’s parish church and a joint statement in support of the march by the Anglican Bishop of Liverpool, David Sheppard, the Catholic Archbishop of Liverpool, Derek Worlock, and leading members of the Methodists, the United Reformed Church, the Baptist Union and the Salvation Army.

In 1981 it was decided that a great People’s March for Jobs would be held to draw attention to high unemployment. It began on 1 May 1981 in Liverpool at the Pier Head when 500 unemployed people began their 280 mile march to London. This was preceded by an ecumenical service in Liverpool’s parish church and a joint statement in support of the march by the Anglican Bishop of Liverpool, David Sheppard, the Catholic Archbishop of Liverpool, Derek Worlock, and leading members of the Methodists, the United Reformed Church, the Baptist Union and the Salvation Army.

The 500 marchers were the most that the organisers could afford to adequately clothe and feed and the initiative drew comparisons with the Jarrow March of 1936.The march ended on 1 June with a rally outside the Greater London Council, a lobby to Parliament and a party in the evening before the 500 dispersed. The marchers handed the government a petition with 250,000 signatures calling on the government to change its policies to ensure full employment. Here’s the original cinema advertisement:

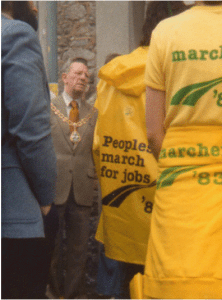

Following the 1981 march, a second People’s March for Jobs was organised in 1983 by the Wales and Scottish TUCs and the TUC regional councils. The main march route was Glasgow to London. 60 marchers set off from Glasgow on April 23 but the numbers had grown to 500 by their arrival in London on June 3. However, it was long argued that unemployment was affecting communities across the nation. To involve many more localities feeder marches were organised from Great Yarmouth, Liverpool, Hull and Halifax. The South West contingent began the long walk from Lands End and on route arrived at Torquay’s Unemployed Centre to be welcomed by the mayor, local trades unions and community activists (pictured below left). The unemployed marchers wanted to prove that they couldn’t be the lazy scroungers targeted by the Press if they were willing to walk 265 miles. There was a festival at the Crystal Palace on June 4 and a rally in Hyde Park on June 5.

Unemployment declined through most of the 1990s and fell below one million for the first time since 1975 in March 2001. Now most Unemployed Centres have disappeared. The old building that was occupied by Torquay’s Unemployed Centre was closed and demolished to be replaced by the Leonard Stocks Centre for the homeless (pictured right). Indeed, that part of Factory Row – hidden behind Castle Circus – has had a long association with the poor, homeless and transient since the end of the First World War when we saw soup kitchens in the same area. The nature of poverty keeps changing and Factory Row changes with it.

Unemployment declined through most of the 1990s and fell below one million for the first time since 1975 in March 2001. Now most Unemployed Centres have disappeared. The old building that was occupied by Torquay’s Unemployed Centre was closed and demolished to be replaced by the Leonard Stocks Centre for the homeless (pictured right). Indeed, that part of Factory Row – hidden behind Castle Circus – has had a long association with the poor, homeless and transient since the end of the First World War when we saw soup kitchens in the same area. The nature of poverty keeps changing and Factory Row changes with it.

To quote the Trades Union Congress: “The reasons why the centres were set up have not gone away. The fight for full employment, against poverty and for social justice is as important today as it was in the 1980s. Job insecurity remains a key feature of the modern world of work. Unemployment remains a trade union issue, affecting people whether they are in work or not. Unemployment is still the greatest cause of poverty and permeates through all aspects of our communities.”

To quote the Trades Union Congress: “The reasons why the centres were set up have not gone away. The fight for full employment, against poverty and for social justice is as important today as it was in the 1980s. Job insecurity remains a key feature of the modern world of work. Unemployment remains a trade union issue, affecting people whether they are in work or not. Unemployment is still the greatest cause of poverty and permeates through all aspects of our communities.”

It used to be that the great dividing line was between those in work and the unemployed – if you had a job, you were reasonably well off. Now while unemployment has been falling, many of the new jobs we have are part time, low paid and insecure. Millions of households struggle to make ends meet even though they include at least one adult in full-time work. Living standards have declined since 2008 despite the economy’s return to growth with children being at particular risk of a life in poverty. 2.6 million households, or 60% of those where the total income is below a minimum income standard, include at least one working adult. About 600,000 households are living below the minimum income standard – despite every adult being in full-time employment. The old libel about the poor being lazy is becoming heard less as the economy changes and secure well-paid work becomes harder to come by.