“Lo! time shall come, when on yon throng’d parade

Shall groups assemble, swains and many a maid,

And elder dames and sires, in converse gay,

Breathing sweet health fresh-wafted from the bay

And yonder hills all boasting purest air

Shall smile with villas and with mansions fair;

Adorn’d with gardens or with paddocks green

These scatter’d round shall on the heights be seen.”

In 1816 Thomas William Booker-Blakemore wrote his poem ‘On Torquay’.

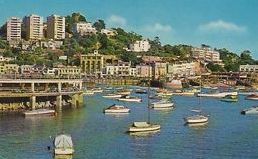

The poem was written at the inception of the town’s remarkable evolution. From humble beginnings, over the next hundred years Torquay would be a new type of community, a seaside resort, which reworked a cluster of hamlets into the richest town in England. In doing so, it became an arena of new ideas and an artistic and cultural centre in a remarkably beautiful location.

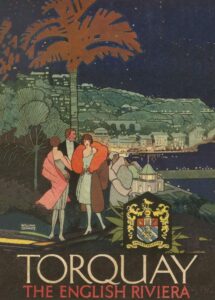

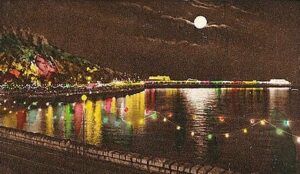

To replicate the attraction of the Mediterranean, the town’s fabric took on exotic styles with tropical plants suggesting romantic images of warmer climes, further promoting the idea of an English Riviera. These constructions were the product of the need for tourist beds and processes that defined their use in specific leisure activities: theatre-going, bathing, sunbathing, yachting, and promenading.

As a coastal resort Torquay occupied a position on a boundary. This was, for visitors, a special and glamorous setting, on the edge, more intense than reality, where everyday rules and restrictions did not apply.

Imitation of the foreign and the faraway further emphasised the seaside as a liminal place, the term coming from the Latin ‘limen’, meaning ‘threshold’. Liminal places offer a break from the normal, an escape from the daily grind of social responsibilities where the stresses of life can be forgotten; where cultures merge to suggest an egalitarian alternative as the constraints of class are suspended for a few weeks.

The town presented a smiling face, but it was always intended that visitors would swiftly leave and return to their homes and re-enter the orderly world of work and commitment.

Nevertheless, the permanent population would increase as others came to stay and make their homes in the town. Each had their own reasons. They came for work, to begin again, to escape past lives and relationships, to retire in an exaggerated form of holiday. All had a common aspiration to live a good life expressed in institutions and activities. And, initially the town may well have met those expectations.

Yet, those imagining that by relocating to the resort that they would leave their concerns behind them found a place with similar disputes, often around religion, social class and wealth disparity; some even more intense than those they had left behind. Indeed, as the town was focussed on a single fragmented service industry, few self-help and mutual aid organisations had flourished and political power remained in the hands of the few.

Some incomers found the out-of-season town a harsh place to reside as they experienced the realities of irregular employment and lack of opportunity; even the calm and tranquil sea becoming agitated and frightening. As Mick Jagger remarked in 1964, “Torquay’s a great town. But I shouldn’t think there’s much to do in the winter”. Nevertheless, only the young, ambitious and determined seemed able to relocate. The old aphorism was that no-one ever leaves Torquay, once seduced by the lifestyle, the beauty, or perhaps they just become susceptible to that fabled seaside lethargy.

In 1916, two centuries after Booker published, the poem was being hailed as having successfully predicted the town’s destiny; and even though it was wartime, most expected a return to Edwardian certainties once hostilities ceased.

Another hundred years would bring a further reinvention in the twenty-first century as Torquay took on the characteristics of other provincial conurbations. Shopping had relocated to out of town retail centres; consumer choice had expanded hugely; increasing numbers of residents commuted to their place of work; and many families and the retired achieved higher standards of living than ever before.

The nation’s increasing affluence had, however, challenged the town’s core identity as a premier resort.

By the early years of the millennium there were pockets of real deprivation around the old town centre and further out in the estates. The local economy had become known for casual labour, high numbers of small businesses, low wages, long hours and seasonal unemployment. The consequence was an increasing polarisation between wealth and relative poverty.

By then the townscape had been transformed; a new Fleet Street while apartments replaced the old villas. All buildings have a built-in obsolescence, inevitably lagging behind as new technology accelerates social change, transforming work, entertainment, shopping and leisure.

Iconic Victorian buildings were consequently seen as anachronisms and some would disappear, such was the fate of the Marine Spa as it was replaced by the brutalism of Coral Island. The unviable were abandoned, prey to the vandal, refuge for the homeless and addicted, prone to fire and ultimate demolition.

This was the consequence of that quest for relevance and modernity, reflecting an ongoing pressure to replicate England’s other urban centres. As Joni Mitchell reminded us, “You don’t know what you’ve got till it’s gone”.