“I think of Torquay as being the home of British comedy. The first time I saw Bruce Forsyth was in the Babbacombe Pavilion in the mid 50s; we had a very successful Monty Python shoot there in 1970; it was then that I met the famous Donald Sinclair, the model for Basil Fawlty…” John Cleese in 2008.

It seems likely that John wasn’t being entirely serious. However, the town does have a long association with stage and screen comedy. Indeed, you could use Torquay’s comedic history as a metaphor for the rise and fall, and rise again, of the resort’s fortunes.

In 1800 Torquay only had a population of 838. Even by the early 1840s this was around 6,000. Then in 1848 the railways arrived and brought mass tourism. By the end of the century Torquay had a population of 25,000; in 2000 it was 65,000. This was a town built on tourism and designed to satisfy the desires of the paying visitor.

In 1800 Torquay only had a population of 838. Even by the early 1840s this was around 6,000. Then in 1848 the railways arrived and brought mass tourism. By the end of the century Torquay had a population of 25,000; in 2000 it was 65,000. This was a town built on tourism and designed to satisfy the desires of the paying visitor.

Along with other resorts, entertainment was essential to Torquay’s success. From the town’s many inns, music halls and beer houses, to the great theatres, comedic performances were an indispensable part of the tourist offer.

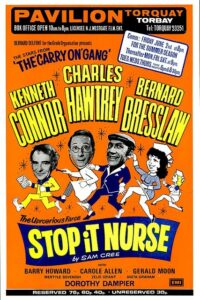

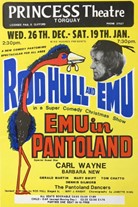

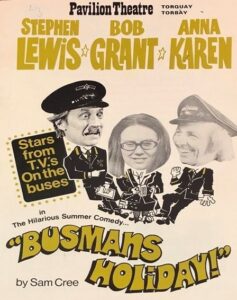

But Torquay was always different. It incessantly campaigned for the title of the nation’s premier resort. Hence, top variety shows were always on offer to attract the ‘right type’ of tourist, with venues presenting the stars of British TV and cinema, often in stage versions of familiar comedy series. These performers catered to the expectations of a steady and reliable stream of visitors over lengthy summer seasons. As there would always be a new audience every two weeks, innovation wasn’t required.

But Torquay was always different. It incessantly campaigned for the title of the nation’s premier resort. Hence, top variety shows were always on offer to attract the ‘right type’ of tourist, with venues presenting the stars of British TV and cinema, often in stage versions of familiar comedy series. These performers catered to the expectations of a steady and reliable stream of visitors over lengthy summer seasons. As there would always be a new audience every two weeks, innovation wasn’t required.

These productions would run for several months, and so recognisable stars would take up residence in the town’s hotels and villas, walk the streets, and visit the restaurants. This gave Torquay a glamorous reputation, a kind of British Hollywood.

These productions would run for several months, and so recognisable stars would take up residence in the town’s hotels and villas, walk the streets, and visit the restaurants. This gave Torquay a glamorous reputation, a kind of British Hollywood.

To take just a few of the comedy legends that performed in the theatres, we have, Harry Worth, Little and Large, Max Bygraves, Dick Emery, Russ Abbot, Mike and Bernie Winters, and the Carry On team. When the Princess Theatre opened in 1961, Tommy Cooper and Morecambe and Wise shared the billing.

Yet Torquay was always too small and limited a stage for its home-grown talent who found they needed to move away. As did, for example, local schoolteacher Arnold Ridley. It was Arnold who wrote ‘The Ghost Train’ which was adapted for both the theatre and cinema. But perhaps he is better known as Private Charles Godfrey from Dad’s Army.

Yet Torquay was always too small and limited a stage for its home-grown talent who found they needed to move away. As did, for example, local schoolteacher Arnold Ridley. It was Arnold who wrote ‘The Ghost Train’ which was adapted for both the theatre and cinema. But perhaps he is better known as Private Charles Godfrey from Dad’s Army.

Further Torquay exports include: leading figure of the 1960s satire boom, Peter Cook; Emily Perry, known as Madge Allsop, Dame Edna Everage’s silent ‘bridesmaid’; and, more recently, Miranda Hart.

Further Torquay exports include: leading figure of the 1960s satire boom, Peter Cook; Emily Perry, known as Madge Allsop, Dame Edna Everage’s silent ‘bridesmaid’; and, more recently, Miranda Hart.

Other famous comedians retired to the Bay after long careers. Though now mostly forgotten, Cyril Maude (pictured) was known as ‘England’s Greatest Comedian’. He and wife Winifred Emery were amongst the highest regarded English stage and screen personalities during much of the inter-war Golden Age. Cyril died in Torquay in 1951.

Other famous comedians retired to the Bay after long careers. Though now mostly forgotten, Cyril Maude (pictured) was known as ‘England’s Greatest Comedian’. He and wife Winifred Emery were amongst the highest regarded English stage and screen personalities during much of the inter-war Golden Age. Cyril died in Torquay in 1951.

More recent residents include the Scottish husband and wife duo, Ian and Janette Tough, also known as The Krankies.

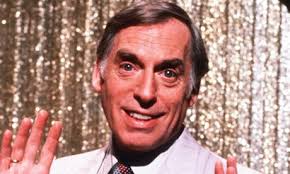

For several years in the mid-80s Torquay was home to Larry Grayson, one of the first television comedians to suggest being openly gay. His act was based on anecdotes, often around his fictitious friends which included Everard (say it slowly), Slack Alice and ‘Pop it in Pete’ the postman. Even today the innuendoes can seem pretty blatant though most went over the heads of younger members of his audience.

For several years in the mid-80s Torquay was home to Larry Grayson, one of the first television comedians to suggest being openly gay. His act was based on anecdotes, often around his fictitious friends which included Everard (say it slowly), Slack Alice and ‘Pop it in Pete’ the postman. Even today the innuendoes can seem pretty blatant though most went over the heads of younger members of his audience.

There’s a bit of a debate here over whether Larry was a help or a hindrance to equality. Did he reinforce a camp stereotype and cause a thousand playground slurs, or did he bring an openly gay, charming, and likable character into millions of homes? This was a time when the BBC officially claimed stars like Larry and John Inman were just “waiting for the right woman to come along” because no-one could be openly gay on family-time TV.

And this opens up a further discussion about comedy. Is there a liberty to punch down, or the duty to challenge inequality and punch up? Certainly, the Bay’s comedy wasn’t always gentle and inoffensive. Jim Davidson, for example, performed often in Torquay and kept a boat in the marina.

And this opens up a further discussion about comedy. Is there a liberty to punch down, or the duty to challenge inequality and punch up? Certainly, the Bay’s comedy wasn’t always gentle and inoffensive. Jim Davidson, for example, performed often in Torquay and kept a boat in the marina.

Then came the movies and TV series filmed in the Bay, attracted by cheap locations, exotic backgrounds, and the eagerness of locals to do almost anything to be involved.

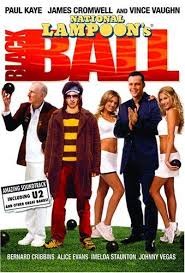

Torquay appears, often impersonating other places, in Arthur Askey’s ‘Bees in Paradise’ (1944), Kenneth More’s ‘Brandy for the Parson’ (1952); Christian Slater’s ‘Churchill: The Hollywood Years’ (2004); Paul Kaye’s ‘Blackball’ (2004); and a variety of TV shows such as ‘The Goodies’ (1976).

Torquay appears, often impersonating other places, in Arthur Askey’s ‘Bees in Paradise’ (1944), Kenneth More’s ‘Brandy for the Parson’ (1952); Christian Slater’s ‘Churchill: The Hollywood Years’ (2004); Paul Kaye’s ‘Blackball’ (2004); and a variety of TV shows such as ‘The Goodies’ (1976).

Yet real comedy fame came in 1970 when the Monty Python team utilised the Bay in a series of sketches. The Pythons stayed at the now-demolished Gleneagles Hotel where they encountered the eccentric hotel proprietor, Donald Sinclair and his wife, Beatrice. Basil and Sybil Fawlty were subsequently born. Sadly, although the hotel, storylines and characters were set in Torquay, the show was never actually filmed on the English Riviera.

Nevertheless, Fawlty Towers left a long folk-memory of bumbling, class-obsessed, low quality Torquay hotels. By the early twenty-first century, however, the hope was that the resort was no longer populated by the idiosyncratic, the deluded, the desperate, and the damaged…

Then came ‘The Hotel’…

This was a fly-on-the-wall television documentary series, initially semi-serious until the second series moved to Torquay’s three-star ‘Grosvenor Hotel’. Channel 4 then hit comedy gold.

This was a fly-on-the-wall television documentary series, initially semi-serious until the second series moved to Torquay’s three-star ‘Grosvenor Hotel’. Channel 4 then hit comedy gold.

Filmed using fixed cameras positioned in several locations around the complex, it featured a real-life cast of local eccentrics and became hugely popular; even being credited with accidentally creating the new genre of ‘Comedy-Documentary.’

But perhaps ‘The Hotel’ wasn’t what our tourism leaders saw as ideal promotional material. On the other hand, as Torquay visitor Oscar Wilde once said, “There’s only one thing in the world worse than being talked about, and that is not being talked about.”

To close, we return to the Pythons who followed up their Flying Circus success with stage shows, numerous albums, books, and a stage musical. They also made movies and in 1979 released Monty Python’s ‘Life of Brian’. The film was immediately attacked by Church leaders for allegedly lampooning Jesus. It had a particularly bad reception in the West Country and, even though the Python team insisted that it was a send-up of religious obsession and 1950s Hollywood Bible epics, eleven local authorities decided to ban it. A further twenty-eight, including Torquay, gave it an X certificate, which meant that it could be seen only by over-18s. As the film’s distributors refused to allow it to be shown with this certificate, ‘Life of Brian’ was effectively banned in Torquay too.

The film was immediately attacked by Church leaders for allegedly lampooning Jesus. It had a particularly bad reception in the West Country and, even though the Python team insisted that it was a send-up of religious obsession and 1950s Hollywood Bible epics, eleven local authorities decided to ban it. A further twenty-eight, including Torquay, gave it an X certificate, which meant that it could be seen only by over-18s. As the film’s distributors refused to allow it to be shown with this certificate, ‘Life of Brian’ was effectively banned in Torquay too.

This prohibition went unnoticed until the organisers of the Bay’s 2008 Comedy Film Festival had to get special dispensation after discovering that the film was still on the local authority’s blacklist, 29 years after its release.

Now that’s Torquay comedy.

‘Torquay: A Social History’ by local author Kevin Dixon is available for £10 from Artizan Gallery, Lucius Street, Torquay, or:

https://www.art-hub.co.uk/product-page/torquay-a-social-history-by-kevin-dixon