“Oh You Pretty Things,

Let me make it plain,

You gotta make way for the Homo Superior”

David Bowie

There may be something about Torquay. Not only did the most notorious magician of the twentieth century, the Great Beast 666 himself, Aleister Crowley, make his home here, so did the single most important occultist of the nineteenth century.

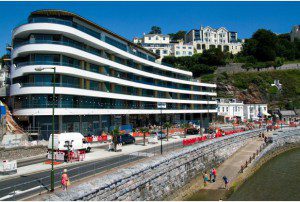

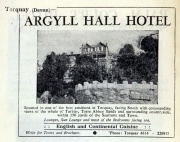

This was Edward Bulwer-Lytton (1803-1873). Edward died on January 18 1873 at his Torquay home Argyll Hall on Warren Road, having lived there since 1867. Built in 1849, Argyll Hall became the Roseland Hotel and is now an apartment block called Marine Palms. The house occupies a prominent position on Rock Walk and can be seen as you head towards the harbourside from the Paignton direction.

Edward was a hugely successful poet, playwright, and novelist. In addition to his writing, he had an impressive political career, serving twice in Parliament, first as a Whig Radical, then a Conservative MP, and going on to the House of Lords as Baron Lytton. While Secretary of State for the Colonies, towns were been named after him in British Columbia and Australia.

Nowadays, however, he is unfortunately perhaps best known for comedy purposes. Since 1982 the English Department at California’s San Jose University has sponsored the Bulwer-Lytton Fiction Contest for the worst beginning to an imaginary novel. This was inspired by the first line of Edward’s ‘Paul Clifford’ (1830):

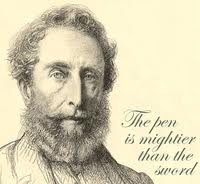

Otherwise, Edward is now mostly forgotten. Yet, his twenty-five novels are the source of a number of phrases that have become clichés. These include: ‘the great unwashed’; ‘pursuit of the almighty dollar’; and ‘the pen is mightier than the sword’.

In the late nineteenth century Bulwer-Lytton was one of England’s most popular novelists, and has been called the father of a variety of genres such as: the English detective novel; science fiction; the fantasy novel; the thriller; and the domestic realistic novel. In 1831 Mary Shelley asked: “What will Bulwer become? The first author of the age? I do not doubt it. He is a magnificent writer.” He’s also responsible for the fashion of black evening dress for men.

Other admirers of Edward’s work include fellow Torquay residents, Aleister Crowley, and two-times Nobel Prize winner George Bernard Shaw. Bulwer-Lytton’s works of fiction and non-fiction have been translated into many languages. In 1879, his ‘Ernest Maltravers’ was the first complete novel from the West to be translated into Japanese.

His entry in the 1893 Dictionary of National Biography covers more than seven pages. His work influenced, amongst others, Wilkie Collins, Thackeray, Trollope and Charles Dickens. He actually persuaded Dickens to give ‘Great Expectations’ (1860) a more upbeat ending. Dickens, a lifelong friend, named a son after him.

His home life similarly attracted attention. He was married to Rosina (1802-1882), a famous Irish beauty who was also an author of thirteen novels. After the disintegration of their relationship, Edward had her incarcerated in a lunatic asylum, although Rosina proved that she was sane and was soon released. She then spent forty years tormenting her husband, revealing details about his mistresses and illegitimate children. She even alleged a sexual relationship between Edward and Disraeli.

While Bulwer-Lytton may be neglected today there are a couple of his themes that are worth exploring. The first is that several of Edward’s novels were made into operas. For instance, the first opera composed in the United States, Leonora by William Henry Fry, is based on his play ‘The Lady of Lyons’.

One opera became far more famous than the novel. This was ‘Rienzi, the Last of the Tribunes’ (1835). Taking the novel as a source, Richard Wagner wrote ‘Rienzi, der Letzte der Tribunen’ (commonly shortened to Rienzi). The opera in five acts was first performed in Dresden on October 20 1842, and was the composer’s first success. Rienzi apparently had a particular appeal to some audience members, possibly due to its theme. The opera is set in Rome and is based on the life of a medieval hero who succeeds in raising the power of the people. An ungrateful proletariat nevertheless forces Rienzi and a few supporters to make a last stand.

One such enthusiast was Adolf Hitler. There is a story that the adolescent Hitler saw the opera in 1906 or 1907. He was so influenced by Rienzi’s heroics that it determined his political career and, it is claimed, that he later told Winifred Wagner that “in that hour it all began”. This tale has, however, been dismissed by scholars. Fortunately then, we can’t trace the origins of the Second World War back to a resident of Warren Road. Nevertheless, Hitler did possess the manuscript of the opera. He had requested and been given Rienzi as a fiftieth birthday present in 1939, and had it with him in his Berlin bunker at the very end of his dictatorship.

The second area in which we see Edward’s influence is in the occult, supernatural and science fiction genres. One of the first psychic investigators, he was recently referred to as the ‘Stephen King of his era’. Edward’s ‘The Haunters and the Haunted ‘(1859) is recognised as the first modern haunted house story and still appears in anthologies alongside MR James and Edgar Allen Poe. The American horror author HP Lovecraft called it, “one of the best short haunted-house tales ever written”.

Edward certainly had an in-depth knowledge of the occult, being at the centre of several occult circles, and he included esoteric ideas in his work. He was the author of ‘Zanoni’ (1842), possibly the most influential occult book of the nineteenth century. This earned him the respect of the leading figures of the nineteenth century occult revival. Consequently, a number of societies claiming hidden knowledge have seen him as one of their own. He has been suggested as a member of, amongst others, the Rosicrucians, Theosophists and the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn. Debate continues over how close he actually was to these groups.

One of his most popular excursions into the occult was ‘Vril, the Power of the Coming Race’ (1871). This novel contributed to the birth of the science fiction genre – HG Wells was impressed and it has been quoted as the first of a dystopian tradition of oppressive future societies that led to George Orwell’s ‘1984’ and Huxley’s ‘Brave New World’.

It relates the story of a race of subterranean super beings waiting to reclaim the surface of the earth from the human race. It also features a source of energy called ‘Vril’, a force that can be used to heal, change, and destroy.

Oddly, some readers believed that its accounts were fact rather than fiction. For example, Helena Blavatsky, the founder of Theosophy, claimed that Edward derived the idea of Vril from ancient Indian writings. In 1947 a German rocket engineer Willy Ley claimed that the Nazi Society for Truth was devoted to looking for Vril, while a 1960 popular book speculated on a secret Vril Society in war-time Berlin. Vril has since become associated with bizarre fringe theories about Nazi flying saucers, force-ray cannons and the lost Atlantis. Just do an internet search on ‘Vril’ if you have plenty of time!

Though, along with Edward, the novel has now largely been forgotten, there remains a reminder of how familiar it was to the Victorian public. During the late nineteenth century, the word ‘Vril’ came to be associated with ‘life-giving elixirs’. In 1886 John L Johnston was looking for a name for his ‘liquid life’ beef extract drink. He chose a blend of the words Bovine and Vril, and named the new beefy beverage ‘Bovril’.

Here’s another ‘Vril, the Power of the Coming Race’ reference, David Bowie’s ‘Oh! You Pretty Things’, “You gotta make way for the Homo Superior. They’re the start of a coming race”.

…