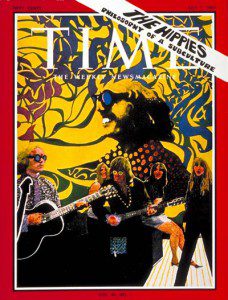

Local history can tell us how we got here. A knowledge of the past can also suggest ways to tackle the problems we now have and can expect in the future. Indeed, we may have faced similar challenges in the past, such as during the 1960s where social upheavals saw the emergence of a worldwide youth culture. During the decade many young people rejected the money, power and status that defined the value system of their parents’ generation. The radicalism of the counter-culture of the hippies saw drugs becoming identified with social change. This spread the recreational use of cannabis and other drugs, particularly new semi-synthetics such as LSD.

Drugs strongly affected the culture of the decade – for example, in the music of the Beatles, the Doors, the Rolling Stones, Cream, the Grateful Dead, Janis Joplin, Bob Marley, Deep Purple, the Who, Hendrix, Dylan, and Joan Baez. The influence of the Summer of Love in San Francisco in 1967 and the Woodstock Festival in 1969 was heard around the world… including Torquay. While political beliefs have always divided opinion in Torquay, after the Second World War came divisions based on age and lifestyle. This became known as the Generation Gap which referred to differences between people of a younger generation and their elders.

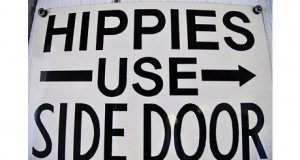

Such mutual suspicions were particularly acute in towns that attracted large numbers of young people – in September 1964 the President of Torquay Trades Union Council complained that, “I did not think that in the 20th century we would have people who would walk about literally stinking.” The unions went on to condemn, “Bohemians and their unhygienic habit of sleeping rough on the beaches, and lounging on street corners, wearing al fresco attire and no shoes and ganging together to block pavements to pedestrians. The holiday season had always attracted a small number of the begging fraternity… now there were more requests from unshaven shabbily dressed and unwashed gentlemen for the price of a glass of coffee. They sleep under the stars or under carefully-erected Corporation deck chairs, the Beacon Quay car park or on the tow path seats flanking the harbour.”

The focus of trades’ union hostility were the beatniks. The original Torquay beatnik pub was The Melville Inn (which then became the Clipper Inn and is now closed and pictured above), focus of the alternative music and poetry scene – the most famous product of which was Donovan who lived on Abbey Road. After a few years Torquay’s beatniks evolved into the hippies and moved to the Rising Sun on Belgrave Road (which is now DTs and pictured below when it was the Old Mill).

The growth of the town’s counter culture was quickly noticed by the authorities. In early 1969 Torbay’s Police issued a statement saying they were keeping an eye on “local hippies” – a Paignton chemist had been burgled and a large amount of drugs was stolen, it was assumed for resale. South Devon’s pub landlords had also been warned to be on the lookout for anyone smoking “oddly shaped cigarettes”.

At 9.30pm on April 12, 1969 around 70 members of the Torbay Drugs Squad and other officers made a drugs raid on the Rising Sun with a warrant to search anyone. This was the first raid of its kind in Torbay.

Some 17 people were arrested – 16 for possession under the Dangerous Drugs Act and one for wilfully obstructing Police Constable James Copeland. The Police had split into groups, each with the task of entering a different bar in the crowded pub. Using a megaphone, the Police ordered all the men to either put their hands on their heads or lapels and the women to cross their arms. Twenty-year-old John Buchan Smith of Teignmouth Road refused to put his hands on his head and told the Police: “This is silly… if you want them raised, you can raise them… you can’t mess me about like this. I want to see a higher authority”. He then used ‘bad language’. An Inspector Anderson issued the order, “Take that one out” and an arrest was made.

John denied he refused to be searched and his defence Hamish Turner said he had been given contradictory orders by the police. Though he had no trace of drugs on him, he did have three previous convictions for allowing premises to be used for the smoking of cannabis. The presiding magistrate described refusing to cooperate with the Police as a “serious offence” and Smith was sentenced to six months imprisonment, suspended for two years.

The conflict between the hippies and the authorities continued. In early 1970 the police told the Torquay Times that the Bay had a small drugs problem among residents, but in the summer this could increase by 50 to 60% because of the influx of visitors: “The drug takers are mostly young people coming down here because it is a nice place. There is plenty of accommodation and they can get casual jobs in bars, holiday camps and hotels.”

Local hippies had been complaining about the attitude of the authorities to their lifestyle for several years. One ex-hippie remembers: “The drug squad were known as the police gardening club because of their fondness for planting stuff on people.”

Whether this is one of those Torquay urban myths is debateable. Yet, some of Torquay’s police did have a reputation for hostility to those that they saw as troublemakers and who could be easily identified by their appearance. In March an anonymous 21-year-old spokesman for the town’s resident hippies claimed that the police were harassing them in order to break up their community before the influx of summer visitors. He said his flat had been raided and that police were putting pressure on landlords to turn him and his friends out of their homes. “They are also tightening up on the places where we meet – trying to get them to close down or to refuse to serve us. They are using the stop-and-search powers more. They’ll stop anyone who dresses differently or who has long hair. They’re really leaning on the communities.” He went on to say that he didn’t believe that the ‘drug traffic’ was the real factor worrying the police in making life unpleasant for hippies. “There is a paranoia in Torbay among the establishment about the alternative lifestyle which they don’t understand. They’re frightened of it. It’s not because we’re a threat to anything individually. I mean we just want to get on with things. But I suppose if enough people thought the way we do, we would be a threat to the system.”

The head of Torbay’s Drugs Squad Detective Sergeant Brian McCreery denied there was a campaign to displace the hippies. “We are just going on as usual – chasing the resident population of drug takers. When the summer comes we will deal with that problem. We are not making any out of the ordinary preparations.” other officers made the point, however, that in tourist resorts where there was a resident hippie community, that resort could expect an invasion of other hippies in the summer months – the inference being that alternatives were always a problem.

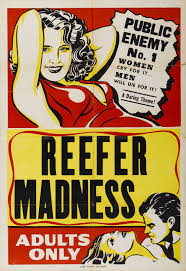

It was the sociologist Stanley Cohen who developed the term ‘moral panic’ after looking at the 1960s Mods & Rockers skirmishes. He believed that media coverage of relatively minor disturbances portrayed all youth subcultures as dangerous threats to society, causing an overreaction from police and politicians. It’s also been suggested that towns that are dependent on tourism develop a particular intolerance of any non-standard behaviour that could ‘frighten off the visitors.’

It may therefore be relevant that other young people were also complaining about alleged heavy-handedness by the police. For instance, students from South Devon Technical College, then situated in Torre, issued a statement criticising the reaction of the authorities during their 1970 Rag Week: “We think the attitude of the police was diabolical”, they wrote. Several students had been threatened with arrest during the usual hi-jinks associated with student fund-raising events. One 19-year-old had his name taken for using a loud hailer, while another was reprimanded for a harmless stunt, reported here in the Torquay Times. “Michael Thomas (19) attempted a ‘transatlantic flight to New York from Torquay Town Hall’. Mr Thomas strapped on his wings, kissed goodbye to his girlfriend and ran off down the main street with arms flapping – he never got off the ground.”

The story of the sixties in Torquay mirrors that of the nation. Local writer and poet Mike Williams was there and has charted the rise and fall of a generation. He remembers, “For a couple of years in the early ’60s The Melville was home to the beatniks. Singing, guitar playing, and even the occasional poetry reading occurred, although the main attraction was cheap rough cider. As the older beatniks moved on, and the last generation appeared, the scene moved to the Rising Sun. There were never any poetry readings here. Although it was packed every night for four or five years, the scene degenerated into drunkenness and despair, reflecting that of the underground Torquay youth culture as a whole.

“The beatnik lifestyle was mainly one of part-time work, the cheapest possible rented rooms, support from the National Assistance Board, and loafing about on beaches and in pubs. At first, that is, from c. 1961, it was magical: life was exciting, it was fun, we were very young, and the possibilities seemed endless. The town itself was imbued with a romantic splendour which few other towns could match. We worked in hotels, on the beaches, on the buses, even sometimes in offices.

“There was, however, a noticeable decline in this almost paradisiacal lifestyle from c. 1965 onwards. Indeed, the end of the beatnik period can be dated absolutely: to the ‘Wholly Communion’ poetry gig at The Albert Hall in London in the autumn of 1965. Beatnik was dead, hippy was in, and the innocence and joy of being young (in our case in Torquay) was lost forever.

“The major cause of this change was the arrival and quick proliferation of drugs. Firstly hashish and amphetamines, then heroin. The arrival of heroin was to prove disastrous for the beatniks of Torquay. A terrible holocaust swept through the town (as it still does) literally killing many of us. It is a holocaust which is un-noticed and unrecorded in the social history of our country, and certainly of Torquay. It needs to be spoken of.

“What the Torquay beatniks were ultimately searching for was a sense of belonging (what they all had in common was fatherless-ness, most being GI babies) and, for a while, this could be found in The Melville and The Rising Sun. But joy turned slowly to despair, as the incursions of drugs grew ever greater. In the end the Rising Sun was raided and the scene, in its last stages, collapsed completely. Mandrex, LSD, and heroin took a greater hold. There are still ‘acid casualties’ walking around Torquay to this day.”

Mike has put together this terrific compilation of photos of Torquay’s Beatniks and hippies:

As the sixties ended the mood had noticeably changed. In 1972 a 100-strong mob of men and women attacked Torquay police station, throwing bricks and bottles. The chant was “Kill the Pigs!”, and officers were assaulted – one later told the court he thought he was going to die. Some in the Love Generation were learning to hate.