“The lawn

Is pressed by unseen feet, and ghosts return

Gently at twilight, gently go at dawn,

The sad intangible who grieve and yearn”.

Torquay visitor TS Eliot

More people believe in ghosts in Torquay than anywhere else in Britain.

We are foremost in a nation of believers. 34% of British people believe in ghosts. One in four (39%) believe that a house can be haunted by some kind of supernatural entity; and 9% of us claim to have actually communicated with the dead.

Women are 10% more likely to believe in the supernatural, 17% more likely to believe in life after death and 15% more likely to think houses can be haunted. That’s even though only 23% of us say we are religious.

These beliefs in the supernatural seem to apply across the Bay. Whenever we present a talk on the topic, around a third of the audience have a personal paranormal tale to tell.

So why that Torquay enthusiasm for ghosts?

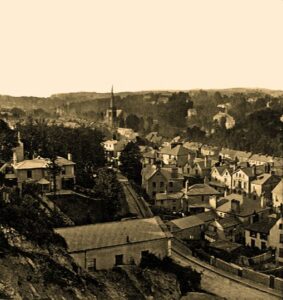

The story of the town’s passion for the supernatural goes back to its very beginnings. By the early nineteenth century our rural superstitions about witches, pixies and the Devil had largely been supplanted by an interest in the occult, a curiosity that encompasses a wide range of beliefs and practices that fall outside of both traditional religion and modern science.

The story of the town’s passion for the supernatural goes back to its very beginnings. By the early nineteenth century our rural superstitions about witches, pixies and the Devil had largely been supplanted by an interest in the occult, a curiosity that encompasses a wide range of beliefs and practices that fall outside of both traditional religion and modern science.

During the Victorian era Torquay acquired a resident population of the wealthy and educated with time on their hands and an interest in exploring concepts beyond the mainstream. In such fertile ground the town became an important meeting place for ideas, attracting many of the nation’s authors of the uncanny. Hence, Torquay developed a reputation for being one of the centres of esoteric thought and practice in Victorian and Edwardian Britain. Ghosts and the practice of communicating with the dead via seances then became part of the town’s metaphysical landscape.

But that doesn’t explain why a local interest in all things preternatural has persisted right into the modern era.

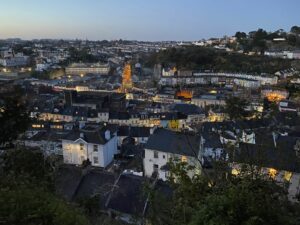

One factor may be the unusual geology of Torquay. We built our town in, and from, a series of steep valleys consisting of a hard grey rock.

One factor may be the unusual geology of Torquay. We built our town in, and from, a series of steep valleys consisting of a hard grey rock.

These canyons are made up of Middle Devonian limestone from around 360 million years ago. Limestone started as corals growing in a shallow tropical sea. And as the sea got deeper and the corals died more corals grew on top until their remains were hundreds of feet thick. Gradually the calcium carbonate of which the corals were made dissolved and cemented with other chemicals to form solid rock.

While limestone is somewhat porous, those cliffs often stream with water when it rains. This indicates its resistant to erosion and is most evident in the two arms of the Bay at Hope’s Nose and Berry Head. It is also full of joints or cracks. As rain is acidic, it dissolved the limestone around the cracks through which it was running. Over many tens of thousands of years these cracks became caves as we see in Kent’s Cavern, Brixham and further afield at Buckfastleigh.

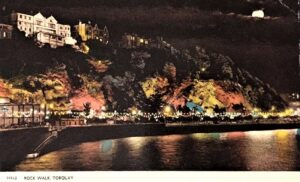

One notable fissure was the Sticklepath Fault, still visible on the cliff face of Rock Walk. This is a major geological fault dating from mountain-building earth movements of around 300 million years ago. It begins in the seabed off the North Devon coast, near Clovelly, runs from the north west in a south east direction, crosses Dartmoor and is exposed in Torquay, before continuing out to sea. The Fault runs through the village of Sticklepath, hence the name.

Movement of the rocks on either side are horizontal rather than vertical and the Fault is thought to be responsible for the earth tremors that were felt throughout our region in November 1955.

The existence of the Sticklepath Fault is undeniable. But some of those interested in Torquay’s esoteric and occult history have subsequently noticed that there are many ghost sightings, paranormal incidents and outbreaks of violence in central Torquay. They then linked these to some supposed numinous power of limestone, and specifically to the Rock Walk fissure.

The existence of the Sticklepath Fault is undeniable. But some of those interested in Torquay’s esoteric and occult history have subsequently noticed that there are many ghost sightings, paranormal incidents and outbreaks of violence in central Torquay. They then linked these to some supposed numinous power of limestone, and specifically to the Rock Walk fissure.

The idea is that some places act either as conduits to other unearthly realms or can store traces of human thoughts or emotions. Back in the nineteenth century some occultists took up this idea of ‘place memory’ arguing that experiences of traumatic events can be projected and recorded onto exceptional locations and ‘replayed’ under certain conditions. The objective was to provide a natural explanation for supernatural phenomena. If that seems familiar, the concept was popularised by the 1972 BBC Christmas ghost story ‘The Stone Tape’.

There is, however, no scientific evidence that limestone has any extraordinary capacities. On the other hand, the Bay’s geology may offer more scientific explanations for at least some ghostly encounters.

Between the beginning and end of the nineteenth century Torquay’s population increased from 800 to 34,000, the resort becoming the richest town in England. Yet with great wealth came real inequality, exploitation, domination, and poverty.

Between the beginning and end of the nineteenth century Torquay’s population increased from 800 to 34,000, the resort becoming the richest town in England. Yet with great wealth came real inequality, exploitation, domination, and poverty.

In 1892 the Canadian tourist Isabella Cowen visited and was shocked at what she witnessed:

“I have seen more luxury since being in Torquay than in all my previous life. And I never saw such pitiable poverty before. Half-clad children with hungry pinched faces and grown up beggars with something worse than either hunger or squalor upon their countenances are to be seen everywhere. All pity for such poor folk in England!”

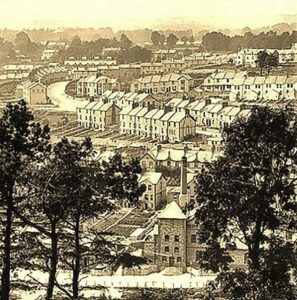

This social division was always between those with a view and those without, the working classes living in cramped conditions in poorer quality housing in the dull ravines of Pimlico, Upton, Swan Street, Torre, and Geoge Street.

T his was also a profoundly imbalanced society. Because of the insatiable demand for female service staff to work in the villas and hotels, there arose a stark disparity in gender. In 1881 there were 19,293 females and 13,665 males in Torquay. Many of those women were young, faced daily exploitation and overwork, living at a time when all was seen through a religious prism. There were numerous mainly Christian denominations and sects competing with visions of heaven, hell, angels, and the Devil. The spiritual was then a relief from drudgery, a source of power for the powerless, and a low-cost recreation.

his was also a profoundly imbalanced society. Because of the insatiable demand for female service staff to work in the villas and hotels, there arose a stark disparity in gender. In 1881 there were 19,293 females and 13,665 males in Torquay. Many of those women were young, faced daily exploitation and overwork, living at a time when all was seen through a religious prism. There were numerous mainly Christian denominations and sects competing with visions of heaven, hell, angels, and the Devil. The spiritual was then a relief from drudgery, a source of power for the powerless, and a low-cost recreation.

Even today Torbay has levels of deprivation that place us in the 20% most deprived areas of England. This equates to 27% of the population.13% of households are experiencing fuel poverty with the highest rates of prepaid electricity meters concentrated in central Torquay and Paignton. These properties predominate in the centre of our towns, many on steep inclines, and are often poorly insulted, inadequately ventilated, and prone to damp.

And it is in these places that we find instances of carbon monoxide poisoning. Gas and coal fires along with common household appliances used for heating and cooking can produce carbon monoxide if they are not installed properly, are faulty, or are poorly maintained.

And it is in these places that we find instances of carbon monoxide poisoning. Gas and coal fires along with common household appliances used for heating and cooking can produce carbon monoxide if they are not installed properly, are faulty, or are poorly maintained.

Symptoms of this colourless and odourless gas include, dizziness, feeling sick or weak, confusion, chest and muscle pain, shortness of breath, headaches, blurred vision, hallucinations, and feelings of dread. The symptoms come and go, getting worse when time is spent in an affected room, but which get better when a person leaves or goes outside. We have long recognised that some ghost sightings are linked to exposure to carbon monoxide.

A further cause of a variety of psychiatric symptoms including mood swings, depression, loss of memory, hyperactivity, and irrational anger, is exposure to the black mould, stachybotrys chartarum. This thrives in places with high moisture levels and is particularly common during the winter when we are less likely to ventilate our homes.

A further cause of a variety of psychiatric symptoms including mood swings, depression, loss of memory, hyperactivity, and irrational anger, is exposure to the black mould, stachybotrys chartarum. This thrives in places with high moisture levels and is particularly common during the winter when we are less likely to ventilate our homes.

The suggestion is that ghosts tend to be sighted in older buildings, which are often more likely to have damp and mould problems.

It is, of course, difficult to positively identify cause and effect. However, these kinds of environmental factors are worth considering when we hear of hauntings.

For example, after Berry Pomeroy Castle was abandoned in the late seventeenth century it became celebrated as an example of the ‘picturesque’. The castle occupies a limestone outcrop overlooking the deep, wooded, narrow valley of the Gatcombe Brook and is mostly constructed from the same familiar hard grey material. It is also known for being the most haunted castle in England.

Whatever the truth – supernatural or science – we’re not done with Torquay’s ghosts. In 1815 the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley visited Torquay. He continues to remind us of the unending search for elusive phantasms and a final solution to the mystery, one way or the other:

Whatever the truth – supernatural or science – we’re not done with Torquay’s ghosts. In 1815 the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley visited Torquay. He continues to remind us of the unending search for elusive phantasms and a final solution to the mystery, one way or the other:

“While yet a boy I sought for ghosts, and sped

Through many a listening chamber, cave and ruin,

And starlight wood, with fearful steps pursuing

Hopes of high talk with the departed dead.”

‘Torquay: A Social History’ by local author Kevin Dixon is available for £10 from Artizan Gallery, Lucius Street, Torquay, or:

https://www.art-hub.co.uk/product-page/torquay-a-social-history-by-kevin-dixon