“Model yachting is a pastime that is growing in favour. Every Briton has an infusion of sea salt in his blood, and if he cannot afford to indulge in the expensive luxury of owning a real racing craft the model yacht offers a very good alternative”. The Tatler (1901)

As the nineteenth century came to a close, Torquay still had a few image issues to sort out. One of these was a bit of an embarrassment as it was pretty much one of the first sights that tens of thousands of visitors to the resort would come across. And it certainly didn’t give the right impression.

Since Torquay’s Railway Station was built in 1859, the vast majority of visitors arrived by rail to what was the premier resort in the nation, and the richest town in England. Everything, of course, had to be perfect.

Actually arriving in Torquay wasn’t the problem. In 1878 the Station had been vastly improved by the architect and engineers William Lancaster Owe and JE Danks. And in response to the Great Western Railway’s expansion into the South West, the impressive Grand Hotel had opened in 1881.

It was then just a short and scenic trip to all those fine hotels in Belgrave Road while a little further was the best accommodation the resort could offer at The Imperial, The Hydropathic, The Royal and others.

It was then just a short and scenic trip to all those fine hotels in Belgrave Road while a little further was the best accommodation the resort could offer at The Imperial, The Hydropathic, The Royal and others.

Hotel transportation and independent carriages would wait at the Station to carry visitors along the Torbay Road… and that is where the source of decades of the town’s shame was to be found. All would be well if passengers looked to their right to gaze across the Bay. However, if they glanced to their left they would see ‘Donkeyland.’

In 1930 Arthur Ellis, in his ’An Historical Survey of Torquay’, described the disappointing view, “A receptacle for all manner of rubbish, ‘mid which grew rank thistles to feed a fat and supine ass, who occupied the grounds for many years”. Hence, Donkeyland (*).

Through this uninspiring landscape, “a turbid stream meandered along its bestrewn channel, and all around were evidences of depressing neglect.”

Through this uninspiring landscape, “a turbid stream meandered along its bestrewn channel, and all around were evidences of depressing neglect.”

This got worse if tourists enquired after the name of the old road that ran alongside the Abbey. They would reluctantly be informed that this ancient causeway was called Rotten Row.

It may well be that tourists would be told that this was a corruption of London’s ‘Route du Roi’, French for King’s Road. It was true that many places in Torquay were named after those in the capital, so we have Belgravia and Pimlico, and Hyde Park does have a Rotten Row, established for William III to travel between Kensington Palace and St James’ Palace. Presumably, this royal explanation would have satisfied those who expected an appropriate appellation for a prominent English Riviera throughfare.

However, there are a number of other Rotten Rows in British towns and cities. In these places the name undeniably comes from ‘rat row’, the Middle English ‘ratton raw’. This suggests a row of houses infested with rats. And we do know that adjacent to the Abbey was an estuary utilised by fishing folk. Furthermore, even today the occasional furry friend can be seen by the stream, as the Council somewhat indelicately informs visitors.

However, there are a number of other Rotten Rows in British towns and cities. In these places the name undeniably comes from ‘rat row’, the Middle English ‘ratton raw’. This suggests a row of houses infested with rats. And we do know that adjacent to the Abbey was an estuary utilised by fishing folk. Furthermore, even today the occasional furry friend can be seen by the stream, as the Council somewhat indelicately informs visitors.

Whatever the derivation of Rotten Row, this embarrassment needed to be sorted out.

In 1877 the boundary wall between the Abbey grounds and Rotten Row was erected and the road raised several feet to its current elevation. A new and more exclusive name was then adopted; ‘King’s Drive, named after Edward VII.

The Council also purchased nearby land from the Mallock estate. Then, for a nominal rent of £5 per annum, later £2 and 10 shillings, Colonel Cary leased to the Council the field between the King’s Drive and the recreation ground.

The Council also purchased nearby land from the Mallock estate. Then, for a nominal rent of £5 per annum, later £2 and 10 shillings, Colonel Cary leased to the Council the field between the King’s Drive and the recreation ground.

These acquisitions allowed the creation of a relatively recent innovation, a public park. Before the 1840s there were no public parks in Britain. There were paved ‘walks’, pleasure gardens and private estate parks, but no areas that were open to all. Then came the Victorian idea of people’s parks, an alternative to drinking or gambling, where the public had the right to enter, exercise, promenade, and engage in healthy pursuits.

Alongside the greensward of the Abbey’s Meadows were henceforth constructed two concrete lakes. The largest was 400 feet long and 40 feet wide. Divided by a rustic bridge, the smaller lake contained two islands for ducks. How the resident fowl were meant to restrict themselves to their allotted territory beyond the bridge was never made plain.

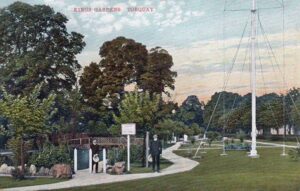

The park was originally named after the King’s consort as Alexandra Gardens, though later retitled King’s Gardens on 19 April 1904. It was officially opened with the presentation of a seventy-foot flagstaff by Mayor Smerdon on 7 August.

The park was originally named after the King’s consort as Alexandra Gardens, though later retitled King’s Gardens on 19 April 1904. It was officially opened with the presentation of a seventy-foot flagstaff by Mayor Smerdon on 7 August.

Clearly identifying its intended use, the larger lake, made accessible by a broad surrounding path, was given the title of ‘Model Boating Pool’. Ellis describes it as” a favourite resort of the juvenile yachtsmen for whom it was specially designed. It is fed from the spring rising in the Sherwell Valley which was diverted for the purpose at the point where it enters the recreation ground”.

Clearly identifying its intended use, the larger lake, made accessible by a broad surrounding path, was given the title of ‘Model Boating Pool’. Ellis describes it as” a favourite resort of the juvenile yachtsmen for whom it was specially designed. It is fed from the spring rising in the Sherwell Valley which was diverted for the purpose at the point where it enters the recreation ground”.

This was another reinvention of the ancient Scire, or clear, Brook; from the utility of providing fresh water to local folk and driving their waterwheels, to replenishing a pocket lake for the amusement of tourists and the formation of juvenile Walter Raleighs.

Model boating was both a long-established component of local seafaring and a recent import. For centuries fishermen made models of their working craft and men and boys came together to sail them; shipbuilders utilised miniature models of vessels under construction and often pitted against each other on small bodies of water.

Model boating was both a long-established component of local seafaring and a recent import. For centuries fishermen made models of their working craft and men and boys came together to sail them; shipbuilders utilised miniature models of vessels under construction and often pitted against each other on small bodies of water.

So, when Torquay began to attract incomers searching for good health, a peaceful retirement, or sedate entertainment, there was already a tradition waiting to be adopted and adapted.

Model boating was already a familiar pastime in the capital where miniature crafts had been sailed on the ponds in the Royal Parks soon after they were opened, the first London Model Yacht Club being founded in 1846.

In consequence, the pastime was considered relatively classless and proved popular across all social strata. It was possible to make your own miniature vessel, purchase a reasonably inexpensive model, or acquire a prestige model yacht or boats. With no membership criteria, entrance fees, expensive equipment, or clothing, all could enjoy the activity. As the 1901 Tatler noted, the pursuit “gives a man opportunities of becoming a skilful sailor without ever having been to sea.”

Indeed, model boating proved to be a social leveller with working class Torquinians and visitors competing and socialising with the wealthy yachting fraternity some of whom sailed models of their yachts out of season. The aged and disabled sailor could also continue their passion when no longer able to ride the waves.

By the beginning of the twentieth century mass production model yachts were an established present for children. For example, Star Yachts, ‘Guaranteed to Sail’, were manufacturing a large range of wooden pond craft and other children’s toys.

By the beginning of the twentieth century mass production model yachts were an established present for children. For example, Star Yachts, ‘Guaranteed to Sail’, were manufacturing a large range of wooden pond craft and other children’s toys.

On the other hand, it is noticeable that, even though such model boats were intended for boys, old photographs indicate how many were accompanied and possibly over-supervised by adults in a vicarious revisiting of childhood. In some images the children are excluded altogether and seem present simply as bored observers.

On the other hand, it is noticeable that, even though such model boats were intended for boys, old photographs indicate how many were accompanied and possibly over-supervised by adults in a vicarious revisiting of childhood. In some images the children are excluded altogether and seem present simply as bored observers.

The ponds were only part of the enhancement of the area. Further showcasing the resort are the Recreation Ground’s Entrance Pavilions and Gates. The ornate octagonal pavilions, built in 1910, with their lead-coated timber canopies were designed as ticket offices with gates for both pedestrians and vehicles.

The ponds were only part of the enhancement of the area. Further showcasing the resort are the Recreation Ground’s Entrance Pavilions and Gates. The ornate octagonal pavilions, built in 1910, with their lead-coated timber canopies were designed as ticket offices with gates for both pedestrians and vehicles.

Few model boats are now to be seen on the ‘Model Boating Pool’. By the latter half of the twentieth century there was a decline in model yachting as other, perhaps more interesting, toys and hobbies emerged to attract men and boys.

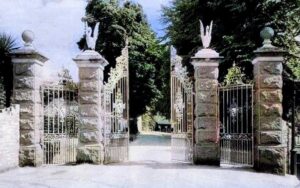

Now we have unofficially renamed both pools as the ‘The Duck Pond’ and the fowl have long since advanced beyond their reservation.  And the ducks are not alone. When the ponds were first opened a pair of swans were donated by Councillor Mortimer. Their brethren reside there still, truculent guardians of the ponds. This gift recognised an old avian association, the swan being prominent on the Cary crest. At the other end of King’s Drive swan statues can still be seen topping the limestone gate piers at the entrance to the Abbey grounds. These gates were erected after the pond which occupied the space was drained.

And the ducks are not alone. When the ponds were first opened a pair of swans were donated by Councillor Mortimer. Their brethren reside there still, truculent guardians of the ponds. This gift recognised an old avian association, the swan being prominent on the Cary crest. At the other end of King’s Drive swan statues can still be seen topping the limestone gate piers at the entrance to the Abbey grounds. These gates were erected after the pond which occupied the space was drained.

If we are looking for yet anther metaphor for Torquay, we have one in the Duck Pond.

If we are looking for yet anther metaphor for Torquay, we have one in the Duck Pond.

A working place for Torquay folk, that became an embarrassment, and then was remodelled and renamed for the affluent tourist. But underground, and in the interstices, remained both a native and imported fauna well able to once again cause discomfort to the privileged.

(*) The fate of the donkey is unknown.

‘Torquay: A Social History’ by local author Kevin Dixon is available for £10 from Artizan Gallery, Lucius Street, Torquay, or:

https://www.art-hub.co.uk/product-page/torquay-a-social-history-by-kevin-dixon