Public toilet, lavatory, bog, public convenience, khazi, loo, the ladies and gents, the water closet, and other, less polite, or regional, appellations. By any other name would smell as sweet.

That we have so many terms about toilets and the ways we use them suggests our British sensitivities. And this is nothing new. Shakespeare and Chaucer included scatological humour in their writing. We even have graffiti, ‘latrinalia’, an anti-art form inscribed on lavatory walls in the form of pictures or words; anonymous, sometimes witty or political, and often pornographic.

Public toilets have consequently always been politicised places. They arouse intense debates around where they should be, who uses them, for what purpose, and whether they should be there at all.

Before the introduction of the public lavatory to the Victorian town, Torquay’s streets and parks were fouled by human waste. Between those limestone cliffs, the streets stank; and the situation was getting worse as the population increased from 5,982 in 1841 to 11,474 a decade later.

Torre Abbey’s medieval garderobe

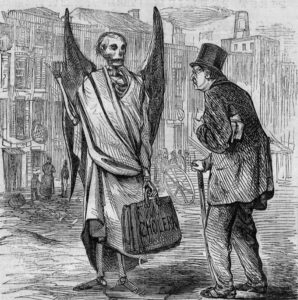

Foul smells were increasingly recognised as being more than just unpleasant, with poor sanitation linked to disease. In 1849 sixty-six Torquay folk died from cholera and dysentery over a period of six weeks. As was to be expected, the cases occurred mainly in the oldest and poorest districts of Pimlico and Swan Street. Many of the dead are buried in Cholera Corner in the churchyard of St. Andrew’s off Lucius Street.

In the 1830s and 1840s cholera came to Torquay

Legislation was passed by Parliament in the form of two public health acts, in 1848 and 1875. Louis Pasteur in the 1860s demonstrated the relationship between microorganisms and infectious disease, causing a huge shift in thinking about illness and sanitation.

Demand for public toilets came as part of the urban need for better sewers and the provision of clean drinking water. Both the technology and the model came in 1851 when the plumber George Jennings installed what he called ‘monkey closets’ to the Crystal Palace for the Great Exhibition of 1851. Also known as ‘retiring rooms’, they included separate amenities for men and women and were the first flush toilet facilities.

People paid a penny to use them and so was born the concept of ‘spending a penny’. This payment ensured patrons received a clean seat, a towel, and a shoeshine. The standard had been established. The next year, London’s first public toilet facilities were opened and known euphemistically as Public Waiting Rooms.

The public toilet then began to appear in cities and towns that prided themselves on being modern and affluent. By the late Victorian era many businesses and local authorities were providing public conveniences in workplaces, railway stations, parks, shops, pubs, restaurants, and other places. The toilets that were municipally owned were usually entered directly from the street. Some were free of charge while others charged a fee. Of course, Torquay, which looked to the capital for many of its target visitors, was amongst the first towns to embrace the innovation. We were ‘Little London’. Yet, while progress in public sanitation undoubtedly helped to improve the cleanliness and health of the town, provision wasn’t implemented equally. Indeed, the presence of public toilets consistently reflected class and gender inequalities in the resort.

Of course, Torquay, which looked to the capital for many of its target visitors, was amongst the first towns to embrace the innovation. We were ‘Little London’. Yet, while progress in public sanitation undoubtedly helped to improve the cleanliness and health of the town, provision wasn’t implemented equally. Indeed, the presence of public toilets consistently reflected class and gender inequalities in the resort.

Local authorities were not legally required to provide public toilets. Nonetheless, the Board, and later the Council, had close links to the tourist industry and so supported any amenities that would attract and retain the ‘right type’ of visitor. The prosperous also arrived expecting facilities beyond those offered by their hotels and rented villas. It further made economic sense for traders who didn’t want tourists to have to regularly return to their accommodation.

The wealthier suburbs of Torquay provided toilets to entice visitors away from the town centre. Hence, for example, both Higher and Lower Chelston had public toilets. In contrast, the town’s less affluent areas had limited provision.

In Victorian towns, public lavatories were often built beneath urban streets or public buildings. These subterranean toilets took up minimal space, were accessible by stairs, and could be lit by glass bricks on the pavement. They also helped to hide ‘objectionable contrivances’ from view. Torquay’s lost examples included those at Brunswick Square, Castle Circus, and the part-underground facility at the top of Lucius Street.

Sensitive modernising at Parkfield

Local health boards built public toilets to a high standard, some being maintained and policed by an attendant, a lucrative position in a resort where gratuities were plentiful. Think of ‘Dan Dann, the lavatory man’, played by Charles Hawtrey in the 1966 movie ‘Carry on Screaming’.

Significantly, however, most early public toilets were solely for men. Victorian society was gender segregated, with the public sphere for men and the private home for women. Female conveniences were viewed as somewhat distasteful and simply not provided. This ensured that most women never travelled much further than where family and friends resided, restricting access to leisure, politics, and employment, a restriction that became known as the ‘urinary leash’.

In response, the Ladies Sanitary Association was formed and campaigned from the 1850s onwards. The importance of the issue was recognised by both sides of the argument.

Some men opposed the siting of women’s toilets next to the men’s and even engaged in sabotage. On the other side of the debate, Torbay’s Suffragettes were very aware of the practical and symbolic need for equal provision.

Corbyn Head, no longer hidden away underground but promoting modern facilities for tourists

Gradually the provision of facilities for women improved. Ladies Rooms began to appear in theatres, railway stations and many other places. Local businesses quickly realised that it made financial sense to keep female shoppers in their premises as long as possible. This offer, on the other hand, did not apply to those women without spending power.

The twentieth century saw Victorian squeamishness fade. It then became a component of our tourist strategy to advertise the public toilet and to reassure visitors that they could spend all day on the beach or shopping and that their toilet needs could always be met. Public conveniences accordingly became much more visible. Note the conveniences at Corbyn Head and the past conversion of the old Rock Walk Toll House.

The old Toll House on Rock Wak, for many years a public convenience

Nevertheless, public toilets persisted as a focus for moral panics, with exaggerated perceptions exceeding any actual threat. Hence, we have seen, in some cases, cash-strapped councils responding to concerns about behaviour in toilets to justify closing them altogether.

One anxiety was around ‘cottaging’, gay men using public toilets for sex. During the later twentieth century the police even used ‘pretty policemen’ to entrap gay men, a practice that actually increased after the 1967 Sexual Offences Act permitted homosexual acts between consenting adults.

More recently the homeless and problematic drug users have been routinely used as an excuse to close toilets. All these are interventions that focus on a minority but then, inevitably, reduce services for the majority.

The closed toilets opposite WH Smiths in the Old Town Hall

Across the nation, the number of public toilets has fallen by around 50% in the past decade, a loss that leads to health and mobility inequality issues for many. One in five people state that a lack of facilities can restrict outings from their homes, particularly an issue for our elderly and disabled; the average age across Britain is 40, in Torbay it is 49. Over half of us restrict our fluid intake due to concern over the lack of toilet facilities, causing serious health ramifications.

While we still have some public amenities in Torquay, we have partly privatised going to the toilet. Shops, bars, and restaurants are now expected to fill in the gaps.

But you usually have to spend money. This may be achieved by purchasing a coffee, which largely defeats the object, or by pretending to be a paying customer of one of our larger pubs. As in the past, some folk just use the street.

And so, the debate over our public toilets has gone full circle. Both the old Torquay stench and the urinary leash have returned.

Torquay: A Social History by local author Kevin Dixon is available for £10 from Artizan Gallery, Fleet Street, Torquay, or:

https://www.art-hub.co.uk/product-page/torquay-a-social-history-by-kevin-dixon