‘The Black and White Minstrel Show’ finally died of embarrassment in the summer of 1987, with a stage tour of three Butlins resorts (Minehead, Bognor Regis and Barry Island). The Minstrel tradition had lasted longer in Britain than in the US and Minstrel shows were a regular attraction in Torbay’s theaters for much of the twentieth century. This light entertainment show ran weekly on the BBC from 1958 to 1978 presenting traditional American minstrel songs, show and music hall tunes. It featured lavish costumes and included “comedy interludes”. Now it seems remarkable how hugely popular ‘The Black and White Minstrels’ once were.

By 1964, the show was achieving viewing figures of 21 million. The theatrical show ran for 6,477 performances from 1962 to 1972 and established itself in ‘The Guinness Book of Records’ as the stage show seen by the largest number of people. In 1961 it won a Golden Rose of Montreux for best light entertainment programme and three albums of songs did extremely well – the first two being #1 in the UK Albums Chart while the first of these became the first album in UK album sales history to pass 100,000 sales. Though the TV show was cancelled in 1978, the stage show continued, touring almost every year to city and seaside resort theatres around the UK, including Paignton’s Festival Theatre (pictured below).

The astounding thing was that even then it was seen as one of the most racist shows in the history of television. The cast comprised of a group of white singers performing in blackface, with curly wigs, white rings around their eyes and smile-enhancing white lips – the make-up eliminated any facial expression other than a look of surprise. Originally the blackface makeup was worn by all performers, but early on it was decided that only the men should black up. Here’s an example of the Show from 1978. For a modern audience it’s jaw-droppingly offensive and still manages to bring in a bit of sexism:

The show began to be questioned on its portrayal of blacked-up characters behaving as stereotypes. There were very few other representations of black people on TV and a large part of ‘minstrel humour’ was based on caricatures of black people as stupid and credulous. As Britain became more multi-racial and multi-cultural the public’s attitude to race gradually grew more enlightened and the show became increasingly controversial. A petition against the Minstrels was received by the BBC in 1967 though it took the Corporation another 11 years to remove the show from our TV screens.

There was also criticism from within the BBC, with comedians in particular mocking the Minstrels – a 1971 episode of ‘The Two Ronnies’ featured a musical sketch, ‘The Short and Fat Minstrel Show’, as a parody, as did ‘Are You Being Served?’, and there’s an episode of ‘The Goodies’ which takes a satirical view of the Minstrels’ popularity. However, though the Goodies’ intention may be good, it’s still difficult to watch and you won’t see its like on the BBC again.

Several famous personalities guested on the show, while others started their careers there. In 1975 Lenny Henry was the first black comedian to appear. In 2009 Lenny explained that he was contractually obliged to perform after winning the ‘New Faces’ talent show and that he regretted his involvement (pictured below): “I was being used as a political football: the minstrel shows were under fire then for blacking up white people, and it meant they could say, ‘Oh, but we’ve got that black kid from the telly, so it’s all right’.”

One of the reasons why the Minstels lasted till 1987 before they were banished from our screens and theatres was that they had been a staple of working class British entertainment for so long. Minstrel shows first gained popularity in around 1830 in the United States where blackface shows translated formal entertainment such as opera into popular terms for a general audience. They quickly attracted audiences overseas, particularly in Britain. White blackface performers used burnt cork and later greasepaint or shoe polish to blacken their skin and exaggerate their lips, often wearing woolly wigs, gloves, tailcoats, or ragged clothes.

Minstrel entertainment was respectable. Across Torbay, as elsewhere in Britain, it was accepted by the church and, for an amusement starved public, was often the only alternative to the risqué performances offered by the music halls. It was a form of family entertainment where parents could take their children without fear of being asked embarrassing questions afterwards. Consequently, it was Torquay’s churches that produced our own Minstrels.

For a number of years in the 1880s, Torquay had several troupes of what were advertised as ‘Negro Minstrels’. James Douglas (pictured above) of St Lukes Church (pictured below) was the organiser of Torquay’s first minstrels, sometimes advertised at the time as ‘nigger minstrel troupes’. These performers came under the names of ‘The Torquay Snowdrops’ and ‘The White Swallows’.

This is from James’ memoirs written in 1901 describing how he organised Torquay’s Negro Minstrels: “In addition to Men I introduced about a dozen Boys, also Altos principally from the Church Choirs which rendered the choruses especially effective. We gave Entertainment not only in Torquay, but also in Paignton, Brixham and Chudleigh, sometimes giving the proceeds to one object and sometimes to another. One night I cleared £14 for the Rowing Club who had their boats damaged in a storm. I gave the proceeds of several to the Hospital. The best we held at the Bath Saloon and at the end of the Concert dancing commenced and lasted until the early hours of the morning, all classes of Society taking part in it, but there was one which I shall never forget.

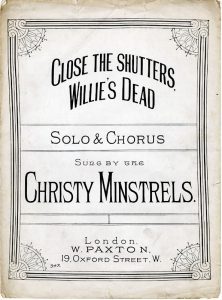

“I arranged it for the benefit of Mrs Lee whose husband, a boatman, was drowned in the Bay. We cleared more than £30 by it. I was centre Man, as usual, and had just sung the song ‘Close the shutters, Willie’s dead’ and was going to respond to the encore when a message came to me that my dear Reg (who was lying ill with typhoid) was dying. I hurriedly got someone to take my place and rushed home and into the sick room where I found him very ill and delirious but I’m thankful to say he was spared to me that was a night never to be forgotten. I had no time even to remove the black from my face. I never ventured to that song again.”

The song James performed that night was an American Minstrel standard from 1872, the topic being the common Victorian theme of a dying child. Today this song appears so maudlin it comes across almost as a parody, but does indicate the Victorian liking for sentimentality and suggests just how common the death of children was in the nineteenth century. Here’s a couple of modern performers with the song. Even they seem clearly embarrassed and we’re not likely to see ‘Willie’s Dead’ performed in Torquay again. Thankfully, we‘re also not likely to see a Minstrel revival in the Bay or anywhere else: