Tucked away around the back of Torre Abbey is a pet cemetery. It’s less Stephen King and more Secret Garden, close to the Sands, and with ancient walls and locked doorways.

When the Abbey was owned by the Cary family this is where they laid their much-loved pets to rest. The small headstones read: ‘Jack – the very best’; ‘Jack II – a dear old friend’; and ‘My Dolly – loving and loved’.

Cockington also has a number of gravestones set close to the church, the burial place of favourite dogs, their names carved in stone. One reads, ‘Beaver – who went to sleep, 23rd June 1928’.

And hidden deep within Haldon Forest is an unofficial and forgotten animal cemetery, the last resting place of hundreds of pets, including dogs, cats, hamsters, horses and even, supposedly, a boa constrictor snake.

While pet cemeteries were long popular in Germany, Britain’s first canine burial ground opened in 1881 in London’s Hyde Park. This new innovation followed the death of a Maltese dog called Cherry whose owner used to walk her in the park each day. He asked the park’s gatekeeper, Mr Winbridge, if his dog could be buried in his personal garden. Mr Winbridge agreed and this established the practice. Over the next few decades hundreds more dogs joined Cherry; over a thousand burials took place before the cemetery became too full in 1976 (pictured below).

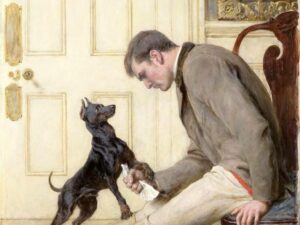

That there was a need for a proper burial place for animals indicates a shift in attitudes. It was during the mid-nineteenth century that the role of cats and dogs in British society altered. Until then they primarily had a working role; cats were used for pest control and dogs for security. Now some animals evolved in their function and began to meet more emotional and companionship needs.

It was at this time that we begin to see a real change in human-pet relationships, marked by growing discussions on animal welfare and the portrayal of our furry friends.

Perhaps of note is that in 1911 the Council of Justice to Animals was formed by a small group of people who were concerned about the methods being used to slaughter animals; and the ways that cats and dogs were being destroyed. These radicals also wanted to improve the welfare of animals by introducing reforms to livestock markets and transport facilities.

Initially, the society set up a number of dispensaries for the animals of the poor and then established branches around the country.

The launch of the Torquay branch, titled ‘Justice for Animals’, was held in early 1912. Crucially, this meeting was attended by those at the centre of Torquay society, and was held at Torre Abbey by invitation of Colonel and Mrs Cary. It had the influence and direct power to make improvements.

Society was indeed changing, and the efforts of the Carys were part of that increasing awareness.

While dogs and cats were generally referred to as companions or friends in mid-century Britain, upper-class late Victorian households began to embrace their pets as being one of the family. Part of this new view included the belief that pets, like their owners, had an afterlife. We then see a growing number of references to owners and pets being reunited after death, in much the same way that humans referred to a deceased partner or spouse.

Also, note the reference to sleep in the Cockington headstone (pictured below).

People perceived death as sleep-like throughout the Victorian and Edwardian periods. Following this equivalence, animal graves began to include a kerbstone and a headstone, so they look like a bed. ‘Rest in Peace’ or ‘Here lies’ came to be common engravings – as they were for their owners.

This led to the Victorian craze for funerary services and rites for animals. Some families would even organise a full funeral that could include choirs, processions, mourners dressed in black, offers of condolences to the family, and sharing anecdotes or pictures they had of the departed beast.

Often a religious ceremony was requested, though the Church usually resisted. Some ministers were known, however, to acquiesce when pressured by an influential ex-owner or when offered an attractive donation.

Yet some saw any belief in an animal afterlife offensive. For example, during the 1880s an Edinburgh woman organised a full funeral procession and cemetery burial for her cat. An outraged crowd dug up the deceased feline and smashed its grave.

Of course, it was very affluent families that could afford to have their pets buried with elaborate headstones or pay hefty inhumation fees. Hence, only around 1 per cent of all pets ended up in the cemeteries. Indeed, most of society generally saw pet funerals as just another peculiar practice of rich folk.

The majority of grieving pet owners disposed of their deceased animals in any way they could. Some did seek public expressions of their heartache and loss, and by 1900 dedicated pet cemeteries had opened around Britain. The majority, on the other hand, buried their loved companions at home in back gardens, marked with makeshift wooden crosses. These fragile memorials quickly rotted and were lost.

It was only the discrete pet cemeteries, with their enduring gravestones, of families such as the Abbey’s Carys and Cockington’s Mallocks that remain to remind us of past inter-species grief.