What was Torquay’s St Michael’s Chapel actually for?

Over the years it has been described as: a sea mark; a light house; a place for lighting a warning fire beacon; the abode of a hermit; a place of retreat; a prison; or a votive chapel built by mariners who had escaped ship wreck.

Unlike other chapels that we have good records for, we have little information on St Michael’s. While most historians assume that the chapel belonged to Torre Abbey, it is certainly a bit strange that episcopal registers and cartularies don’t record its existence.

What we do know is that it is probably 13th or 14th century, is made from local grey limestone rubble with some red sandstone dressings, and is on the edge of a steep sided limestone cliff which may be a former quarry face. The hill was once tree-less and visible from the Bay – the Reverend John Swete on his historic tour in 1783 drew the chapel as being on a barren hillside.

It is a single space, with a slit window on the south side, along with an arched doorway and the stub walls of a former porch. The east end has an unglazed window opening. The west end wall is thicker towards the bottom with a slit window in the gable end wall.

However, there’s even some debate over whether the chapel should even be called St Michael’s. St Michael is a saint of high places, and there are several other St Michaels built on steep hills such as Brent Tor, in Cornwall, and Normandy.

An artist in 1662 called it St Marie’s Chapel, as did John Speed in an old map in 1616. In a deed of 1238 there’s a reference to a hill called la Windiete. One suggestion is that Roger de Cockington built and dedicated the chapel to his wife Maria.

Chapels aren’t uncommon. Around 4,000 parochial chapels were built between the 12th and 17th centuries. These were usually places of worship for parishioners who lived at a distance from the main parish church; or they were built for private worship by wealthy families. Yet, nearby is the medieval St Saviour’s at Torre and the Abbey could even be seen from the site. Therefore, we need to look at another purpose for St Michael’s.

What gives us a clue is the floor of uneven bedrock. A lot of time, money and effort was put into the chapel’s construction but no attempt has been made to cut away or level the rock inside the building. It is very uneven and falls away from east to west, and has never been sealed by a stone, tile or wooden floor covering. However, this rock floor shows considerable signs of wear near the entrance, suggesting significant use over many years. There are traces of original wall plaster with a niche in the south wall which may have been a piscina, a stone basin for draining water used in the Mass.

This uneven floor, alongside the setting on the limestone summit indicates that the chapel was built to mark a sacred space. The proposal is that it was constructed on the site of a religious vision.

Another suggestion is that it is the site of an older place of pre-Christian significance. It was common to build churches on former pagan sites and the Archangel Michael was the field commander of the Army of God in the Books of Daniel, Jude and Revelation. St Michael led God’s armies against Satan’s forces during his uprising, and so, in this view, Torre’s early Christians acquired the site for their new religion. It was established to proclaim dominion over evil, with the chapel – whatever its true name – coming later. These two explanations, of a vision and of a symbolic victory, are not mutually exclusive.

It is notable that Torquay’s Chapel has long been connected with lighthouses, hermits and the sea. From an 1850 book ‘Legends of Torquay’ comes an old story of a mariner who, having been shipwrecked, built the chapel and lived there as hermit, forever watching the place where his ship sank. Some 300 years later his ghost helped the save the life of the fiancé of a Torquay girl called Rosalind.

Admittedly, the chapel was significant for seafarers. A guidebook of 1793 reports that, “The Tor Chapel, perched on the summit of the ridge of rocks, once an appendage of the abbey before us and as it has not been desecrated it is sometimes visited by Roman Catholic crews of the ships lying in the bay.”

However, the lighthouse suggestion is questionable as Chapel Hill is a long way inland, while the cliffs of Waldon Hill would have been more visible for those at sea.

There is also an established association between hermits and lighthouses. During the 1300s, for example, the hermit Nicholas de Legh lived in a cave at Kent’s South Foreland where he lit a lantern every night to guide ships to safety. On the other hand, religious hermits lived on their own to escape the temptations of the world and fled far from human habitation. It doesn’t make much sense to live in isolation only a mile from the richest Premonstratensian abbey in England.

To look for the motivation for these stories we may want to look at a similar St Michael’s Chapel. We know more about this one.

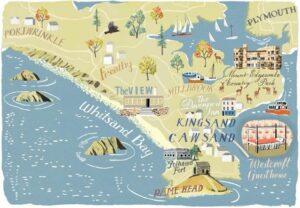

Just over the border in Cornwall is Rame Head Chapel, also dedicated to St Michael the Archangel. This small rectangular, stone-built chapel also has an interior with no decoration and no floor – just earth and rock underfoot. It was originally lime-washed so that it stood out on the headland.

Giving us an idea of when it was built, the chapel was first licensed for Mass in 1397 and may be on the site of a late Celtic hermitage.The location on a high cliff made it idea for watching the western approaches to Plymouth Sound. It also seems likely that there was a resident priest/watchman who slept in a small upper chamber and kept watch along the coast for approaching vessels, lighting a bonfire to act as a warning beacon. It was subsequently used as a lighthouse, beacon and watchtower from as early as 1486. A watchman was employed during the Spanish Armada in 1588.

What may have happened is that what was known about the history and purpose of the Rame Head Chapel was transferred to its visually similar Torquay namesake.

Chapels often became disused as their communities and supporting finances declined or disappeared. The greatest cause of abandonment, however, took place when the Reformation eliminated much of the fabric of Catholicism. The Dissolution of Torre Abbey ejected those who cared for the Chapel; its purpose and importance being suppressed and forgotten over the years. Folk tales and local histories then filled in gaps in our knowledge with imports from other places.

Incidentally, the purpose of Rame Head is remembered in the old song ‘Spanish Ladies’: “Next Rame Head off Plymouth, Start, Portland, and Wight.” A younger generation may know the song from the video game ‘Assassins Creed’: