Why Torquay looks like this…

… & not like Atlantic City which has one of the highest crime rates in America

Every so often there’s a suggestion about turning Oldway or the Pavilion into a casino. We could then be the entertainment capital of the UK, a British Las Vegas or Atlantic City.

We’ve been here before as Torquay and Paignton often need to reinvent their offer to tourists.

Even though the peak of domestic holidays was in 1974, the tourism industry recognised that holidaymaking was changing. Perhaps the most significant indicator of things to come was on 5 May 1962, the first flight of the new airline ‘Euravia’, taking families on an all-inclusive holiday to Spain.

There had been package tours before but rising wages and high employment now offered the average family a new experience. At the same time, Beeching was withdrawing from service the inexpensive trains that had long delivered holidaymakers from the cities.

The traditional resorts were also facing growing competition from other British destinations as the scope of leisure activities increased. A particular challenge came from rising car ownership which offered more flexibility. This led to a higher proportion of day-trippers and a fall in the number of overnight visitors.

Something needed to be done, and solutions were sought by both business-owners and the authorities. For some these measures were to be found in the time-honoured replication of the successes of the Mediterranean resorts.

The promise had always been that Torquay could be a Devonian Cannes, known for its sophistication, a home to the rich and famous serviced by luxury hotels and restaurants.

Casinos had always been redolent of the sophisticated Riviera. They were an amenity that could confirm that Torbay could equal the glitz and glamour of the Cote d’Azur. In addition to being an established feature of a refined and opulent Europe, casinos were at the heart of the exciting cutting-edge consumer culture of the United States.

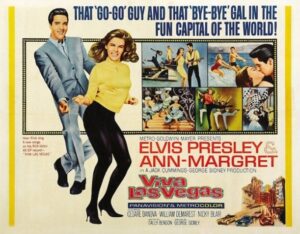

Elvis Presley’s ‘Viva Las Vegas’ (1964)

By the 1970s the public were well acquainted with the concept of entertainment hubs constructed around the roulette table and the slot machine via movies such as Elvis Presley’s ‘Viva Las Vegas’ (1964) and the James Bond Vegas-set ‘Diamonds Are Forever’ (1971).

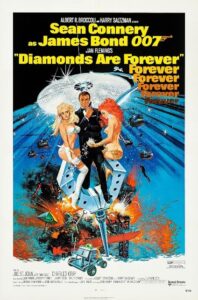

Here was a form of guilt-free gambling associated with a stylish and affluent lifestyle; the urbane tuxedo a fine substitute for the shabby old seaside socks-and-sandals combination. Gambling as glamour: the Las Vegas-set ‘Diamonds Are Forever’ (1971)

Gambling as glamour: the Las Vegas-set ‘Diamonds Are Forever’ (1971)

Just in time we appeared to have discovered another reinvention, capable of attracting investment without heading down-market; a risk-free offer to both old and new visitors.

There was even talk of a Torquay International Airport to fly in all those high rollers.

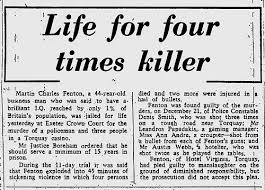

Then on 21 December 1973 six people were shot, four being killed, by a local businessman.

The awful event began when local businessman Martin Charles Fenton was stopped in Rosehill Road by a 44-year-old police constable who had become suspicious of the way that Fenton was driving his Ford Granada. The officer was shot three times.

Fenton then abandoned his own vehicle and left in the officer’s panda car. Forty minutes later the gunman entered the Carlton Casino where he was recognised as a regular punter known as Marty.

Taking turns working on the door that night was 35-year-old Paul Filby. Paul had worked in casinos in London during the 1960s and had been attracted to Torquay by the promise of earning “good money”. He remembers:

“It was a fairly quiet night with just around twenty customers and only a single roulette table operating. I knew Fenton as he had already been banned for causing trouble, though I got on all right with him. As he came in, I grabbed his arm and realised he had a gun right away. I spun him around and I ran back up the stairs. I don’t know why he didn’t shoot me. I then heard a lot of screaming and yelling.”

A customer from Paignton said that he thought a man coming into the club with two guns was “some sort of clown”. He later recalled, “It didn’t sound like a gun. It sounded like some kind of air pistol.”

When the casino’s manager went to challenge Fenton, he was shot twice; a local hotelier, who was playing at one of the tables, was also shot twice. A croupier then approached Fenton saying, “Stop it, Martin. Don’t be silly. Don’t, Martin, don’t!” She too was shot twice and, when she fell to the floor, Fenton shot her again. Another croupier, who lived in the Terrace with her husband, a fellow casino worker, told the court she thought he was going to die,

Another croupier, who lived in the Terrace with her husband, a fellow casino worker, told the court she thought he was going to die,

“My husband dived beneath a table when I saw Marty come towards where he was. As he approached, I saw my husband stand up. He had the gun pointing at him and he said, ‘Don’t shoot, Marty’. My husband said, ‘We have just got married’. And I heard two loud clicks. I expected to see my husband fall. Unbelievably, he didn’t. I don’t know what happened next.”

She said that after the shooting ended, she heard 44-year-old Fenton say, “Marty fixed it then”. Fenton got in his car and drove off. After an eleven-mile and forty-minute pursuit, he was arrested and found to have stabbed himself in the stomach.

Fenton was supposed to have been “driven to fury by gambling losses” and the eleven-day trial at Exeter Crown Court heard that he went to the casino in search of the owner.

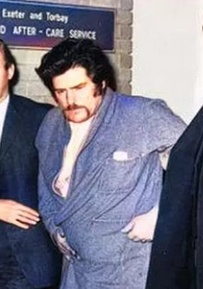

He had thrust one of his guns into a doorman’s stomach demanding, “Where’s the Boss?” The intended victim fled through an emergency exit when Fenton arrived. Martin Charles Fenton was jailed for life and died in prison in 1996.

Martin Charles Fenton was jailed for life and died in prison in 1996.

During his early career, the chef Jacques Marchal was a croupier and he remembered the Carlton Club,

“There was a new casino starting up in Torquay. It was upmarket and they wanted a little of the French suaveness, so I spent a whole summer training all the staff: ‘faites vos jeux’ (‘place your bets’) and all the rest. But there was something about the ambience of the place I did not like. I was not comfortable with it, so I didn’t stay on after that. It sounds corny, but I did not mind taking money off people who could afford it. I did not like taking money off those who could not.”

Ten months after the incident, Torquay magistrates banned gambling at the Carlton after police claimed that customers had been cheated. The licensee, they said, was not a “fit and proper” person to be the holder. He appealed the decision but there were further accusations that illegal gaming was being allowed on the premises. The Gaming Board also investigated allegations that Fenton was granted credit.

Two years later, in an unconnected case, the casino’s owner was convicted of a conspiracy to pervert the course of justice and received three concurrent two-year prison sentences.

The Carlton Casino killings alerted the authorities to the dangers of gambling and the police started taking a great deal of interest in casinos. By 1975 there were just 130 licensed casinos in the UK with the police issuing 108 cautions and initiating 82 prosecutions that year.

Over the following years, proposals to remodel Britain’s resorts as gambling hubs all fell under the shadow of that terrible day in 1973.

Indeed, not just in the Bay but all our coastal towns may have become very different places if not for the casino incident.

Across the world resorts have been transformed by the gambling industry’s vast amounts of cash. Yet while gambling can bring in opportunities and employment, many communities have also seen despair, addiction, prostitution, corruption and organised crime.

The Carlton killings caused a national reappraisal of the direction of travel, and maybe that scrutiny came just in time. Another few years may well have seen Torquay and Paignton transformed into something unrecognisable as the Bay found itself unable to resist the designs of a powerful international industry.

Torquay: A Social History’ by local author Kevin Dixon is available for £10 from Artizan Gallery, Lucius Street, Torquay, or:

https://www.art-hub.co.uk/product-page/torquay-a-social-history-by-kevin-dixon