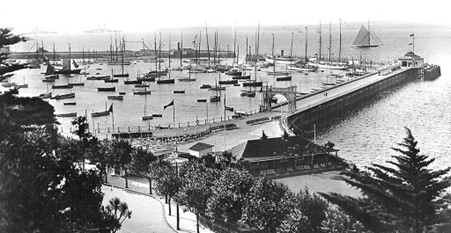

Paignton has a pier; Teignmouth has a pier. But Torquay does not.

We do, of course, have Haldon Pier, built in 1867, and Princess Pier, but they aren’t piers.

A true pier is defined as a structure that water passes beneath, supported by poles or pillars. What Torquay has are harbour walls and breakwaters, solid structures down to the seabed.

It could have been so different.

Very late in the game, in 1878 speculators hoped to construct piers at Torquay, Falmouth and Plymouth for the use of pleasure steamers and promenaders.

And in 1881 and 1883 local groups planned a true pier reaching out from the Palm Court Hotel, now Abbey Crescent, along the lines of those monumental piers that could be seen in Brighton and Blackpool.

These grand plans were all rejected.

To suggest why Torquay is unusual for a tourist resort in not having a pier, we have to go back to the origins and story of that peculiarly British icon.

Originally piers were just landing docks. The first pleasure pier, at Ryde on the Isle of Wight, was built in 1814, and by 1850 there were a dozen piers at British seaside resorts. These were fashionable and select extensions of the seafront promenade which allowed holidaymakers a walkway out to sea; a way of being in the water but above it. These early nineteenth century resorts were generally limited to the upper classes. This would change as the Industrial Revolution raised the income of the average working person. Improvements in transportation brought greater mobility as steam-powered railways, boats and ships created the working-class holiday.

These early nineteenth century resorts were generally limited to the upper classes. This would change as the Industrial Revolution raised the income of the average working person. Improvements in transportation brought greater mobility as steam-powered railways, boats and ships created the working-class holiday.

Consequently, piers became working-class palaces. What had once been a setting for the gentry was transformed into a part of a new holiday culture; the ‘improving’ entertainment of classical concerts giving way to variety shows and amusement rides.

Victorian piers varied from functional braced grids, such as Llandudno’s (built in 1877), to the arches of Clevedon (1869). Iron provided enough rigidity to support a whole range of entertainments and attractions along a pier’s length.  The pavilions built above the decks could reflect inland precedents, such as Brighton Pavilion’s association of Islamic and Chinese architectural motifs. Onion domes and pagodas were common, while grand pavilions such as at Hastings (1872) and Great Yarmouth (1902) could accommodate thousands in their concert halls.

The pavilions built above the decks could reflect inland precedents, such as Brighton Pavilion’s association of Islamic and Chinese architectural motifs. Onion domes and pagodas were common, while grand pavilions such as at Hastings (1872) and Great Yarmouth (1902) could accommodate thousands in their concert halls.

The promenade remained but there were also: theatres; penny arcades; bowling alleys; Punch and Judy shows; minstrels; acrobats; carousels; ice cream; toffee apples; photographers; naughty postcards; music hall songs; smutty comedy; rollercoaster’s; gang fights; ‘What the Butler saw’ machines; and then cinema. And eventually electricity where lighting made nighttime entertainment flourish.

This wasn’t free, however. There was a charge just to enter the turn-style at the foot of the pier. There were further fees for sitting down and entering dance halls.

For many visitors these were an oasis of abandonment where for one week a year working-class people could enjoy the good life. By 1900, there were 80 of these piers, with some seaside towns having two or three.

But not in Torquay.

For well over a century Torquay spent a good deal of its energy in fighting to preserve its elite image. A particular challenge came in 1848 following the opening of railway which began to decant thousands of tourists of all classes to sedate tourist resorts across the nation. Piers particularly appealed to the working and lower-middle classes and their children, a clientele it was believed was more suited to nearby resorts. From the arrival of the railways Britain’s 27 major seaside towns then developed around the type of visitor that they were trying to attract. We then see an informal policy of segregation where social and economic discrimination took hold, sometimes subtle and sometimes not.

Piers particularly appealed to the working and lower-middle classes and their children, a clientele it was believed was more suited to nearby resorts. From the arrival of the railways Britain’s 27 major seaside towns then developed around the type of visitor that they were trying to attract. We then see an informal policy of segregation where social and economic discrimination took hold, sometimes subtle and sometimes not.

Torquay became the richest town in the nation, the leisure centre for the World’s largest Empire. It intended to stay that way and so working-class visitors were redirected to Paignton and other resorts.

Visitors recognised Torquay’s pretentions.

In 1861 Charles Dickens defined Torquay as a “place I consider to be an imposter, a delusion and a snare”. Rudyard Kipling in 1896: “Torquay is such a place as I do desire to upset it by dancing through it with nothing on but my spectacles. Villas, clipped hedges and shaven lawns, fat old ladies with respirators and obese landaus (a kind of carriage).”

In 1923 the Western Times carried on that demarcation, “Torquay is not Brighton, neither is it Blackpool. It stands upon a different plane to these watering places. A higher one”.

Hence, even though proposals for a pier were repeatedly presented, the local Board of Health were not enthusiastic and neither was the town.

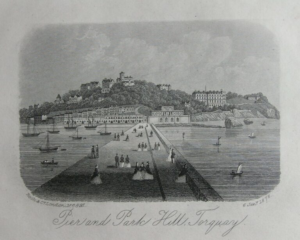

When the local Board took over the harbour in 1883 it was decided a stone pier was required for a new mooring basin. A committee then visited other resorts to view the opportunities to create something special. They weren’t impressed with what they encountered in some of the brasher towns.

The town’s conservatism also asserted itself. A public meeting was held which even turned down the modest offer of a covered band stand. Then a poll of rate payers was undertaken. This rejected the proposal to construct a full-scale pier by 3,194 to 1,296.

I n its place came a much more limited scheme that featured a small pavilion. This was grudgingly accepted. Torquay was not to have a grand pier that may have attracted unsuitable visitors.

n its place came a much more limited scheme that featured a small pavilion. This was grudgingly accepted. Torquay was not to have a grand pier that may have attracted unsuitable visitors.

Work on the pier commenced in 1890 as a simple mass concrete groyne. A steel lattice girder and timber structure was added in 1894, followed by a landing quay on the seaward side of the pier-head in 1906.

Paignton’s true pier

Alongside the emblematic piers, and lack of, this social division is still evident today in the contrasting architectures of Paignton and Torquay.

It can also be seen in the provision of play facilities for children. For decades entrepreneurs submitted plans for child-friendly entertainment around the Strand, including a Paignton Zoo-style miniature railway. All were rejected as not fitting the resort’s image.

Towards the end of the twentieth century Victorian piers became metaphors for tourist resorts across the country. During the 1960s and 70s the package holiday was born and many seaside towns fell into a steady state of decline.

Some piers, once the showcase for their coastal communities, became neglected by amateur or even fraudulent owners, uninterested conglomerates, or local authorities that just couldn’t afford their upkeep. Many were then one-by-one demolished or destroyed by the elements.

Even Torquay’s half-hearted attempt at offshore entertainment came to a premature end.

April 1974 ‘The Islander’ bar goes up in flames never to be rebuilt

In April 1974 fire gutted ‘The Islander’ bar and due to damage to the underlying timber, the building was demolished to deck level. Torquay’s first pavilion was never rebuilt.

So, Torquay doesn’t really have a pier. It has functional and sturdy harbour walls, necessary to protect the harbour and its yachts.

As Britain’s richest town we, no doubt, could have had the best pier in the nation. Yet, even the most impressive ornate iron and timber construction would have faced the same late twentieth century challenges and may well have been, by now, numbered amongst the many lost Victorian piers of Britain.

‘Torquay: A Social History’ by local author Kevin Dixon is available for £10 from Artizan Gallery, Lucius Street, Torquay, or:

https://www.art-hub.co.uk/product-page/torquay-a-social-history-by-kevin-dixon