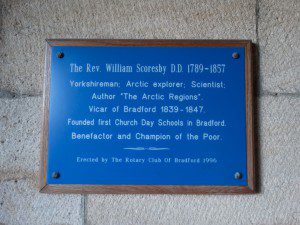

William Scoresby (1789-1857) was an Arctic explorer, scientist and clergyman who ended his days in Torquay.

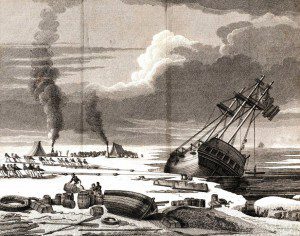

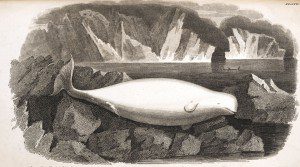

He made yearly voyages to Greenland between 1803-22, at first on his father’s whaler, and then as the captain on other ships. William mapped, charted, made deep-sea temperature soundings, described the flora and fauna, and collected other data along the coasts of Greenland. His last trip to the Arctic was made in 1822 and in 1825 he entered the Anglican ministry. He made a voyage to Australia in 1856 to study terrestrial magnetism.

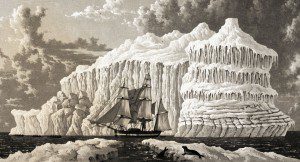

William’s several books on his experiences (illustrated here) helped lay the foundations of modern arctic geography. Many of his papers, log books and instruments are held at the museum in his home town of Whitby. A number of places have been named after him, including:

• The Scoresby Sund fjord system

• The Melbourrne suburb of Scoresby

• Scoresby Land in Greenland

• Cape Scoresby on Borradaile Island, south of the Antarctic Circle

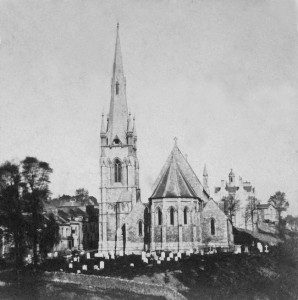

William married three times. After his third marriage in 1849, he built a villa in Torquay, and he was appointed honorary lecturer at St Mary Magdalene Church by Castle Circus.

What is less well known is that William was also a pioneer in the study of animal magnetism, also known as Mesmerism.

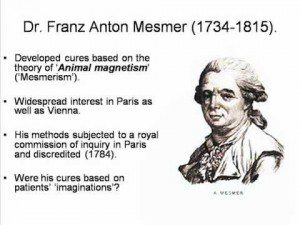

Animal magnetism was conceived by the German doctor Franz Mesmar in the 18th century and was believed to be an invisible natural force exerted by animals. Mesmer, and then William, believed that the force could have physical effects. It was proposed that a fluid or energy was the basis of the cosmos and acted as a life force. When this fluid circulates, living beings are healthy, but when it is blocked we experience sickness. All men, Mesmer believed, had the capability to use the life force for healing purposes. Accordingly, magnetizers (those who have developed their abilities) are able to direct their vital fluid toward a sick person, and heal him or her. This became the basis of a treatment where the magnetiser gazed, made ‘passes’ (movements of the hands near the body), and directed their will at the patient. It could also involve the ‘laying on of hands’.

Mesmerism attracted many followers in Europe and the United States and from its beginnings in 1779 it was an important part of medicine for about 75 years – it continued to influence the profession for another 50 years. More than 1500 books were published on animal magnetism and related subjects.

While William was chaplain of Bedford Chapel, Exeter (1932-39) he became interested in animal magnetism due to his observations on terrestrial magnetism during his polar voyages. In Torquay, he conducted experiments and found he could mesmerize subjects easily. He gave the name “zoistic magnetism” to this hypnosis using his wife as a subject.

William’s research into clairvoyance – the alleged ability to gain information through extrasensory perception – caused him to believe that ‘thought transference’ or ‘community of sensation’ was possible between an operator and a subject. One of his subjects was able to describe food that William tasted and other physical sensations that he was experiencing. Another was immobilized as she sat on a sofa that had been “magnetized” by William and couldn’t move outside an imaginary circle traced on the floor.

William’s book ‘Zoistic Magnetism’ influenced James Esdaile, who claimed to have repeated the experiment using a “magnetized” armchair. Today we are familiar with stage hypnotism, but this was seen as evidence of hidden forces.

On the other side of the argument were members of the medical establishment who were at first suspicious of the treatment and then openly hostile. One of the principal opponents of Mesmerism was Torquay’s, “Charles Radclyffe Hall, MD, Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians of London, and of Edinburgh; consulting physician to the Erith House Institution for Gentlewomen; and physician to the Western Hospital for Consumption; Torquay”.

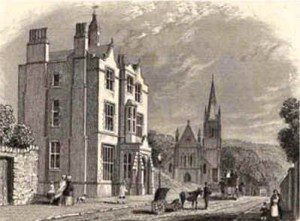

Just a few yards away from Mary Magdalene Church was Charles’ base at Torquay’s original hospital in Higher Union Street (pictured above). In 1845 Charles (pictured below) wrote, “On the rise, progress and mysteries of mesmerism in all ages and countries.” His articles were published in the Lancet whose reformist editor, Thomas Wakley, shared Charles’ anti-Mesmerist views. This was a debate between the Torquay scientist and the Torquay clergyman.

Charles attempted to expose what he believed to be Mesmerism’s contradictions, extreme claims and its scientific weaknesses. Based on his investigations, he concluded that animal magnetism was a product of the imagination and that it had no basis in physical laws. He argued that faith healers do have satisfied customers, though these were due to the power of suggestion and the belief in the therapy – what we would today call the placebo effect. The magnetists may even have created the illnesses themselves using their power of suggestion and cured by exploiting the receptive nature of their subjects. It looks like Charles and his colleagues won the argument – today Mesmerism is almost forgotten.

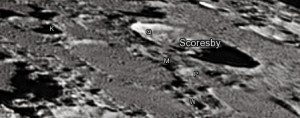

William Scoresby died in Torquay on 21 March 1857. The great explorer of the world and of inner mysteries is commemorated by a memorial in St Mary Magdalene Church, which is decorated with a mariner’s compass and dividers. In more ways than one did William’s influence go beyond this world. If it’s a clear night look upwards, you may just be able to see the crater Scoresby on the moon.