Back in 1853 the Chief Constable of Torquay’s Police, Charles Kilby, complained of the “unbecoming manner that young women of the town wander around the thoroughfares without bonnets and shawls”.

This wasn’t just a snobbish comment on youthful fashion choices. It was code.

The subject was the ‘fallen women’ of Torquay; those that had ‘lost their innocence’ and fallen from the grace of God. Here was the biblical harlot. Indeed, the topic was so troubling and perplexing that even using a precise word to identify the practice was distasteful. And so we see over the succeeding century a variety of euphemisms being employed.

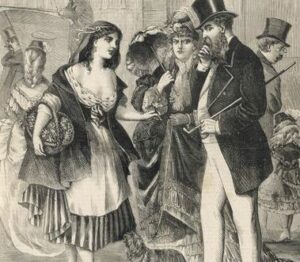

Charles was implicitly recognising that prostitutes dressed in a manner contrary to customary female attire. They often wore gowns made from colourful or flamboyant material that accentuated their body-shape; and to promote their offer they didn’t follow the practice of wearing modest bonnets and shawls in public. The Chief Constable was expressing the concerns of the authorities and many in wider society about the behaviour of these representatives of the town’s female underclass.

Charles was implicitly recognising that prostitutes dressed in a manner contrary to customary female attire. They often wore gowns made from colourful or flamboyant material that accentuated their body-shape; and to promote their offer they didn’t follow the practice of wearing modest bonnets and shawls in public. The Chief Constable was expressing the concerns of the authorities and many in wider society about the behaviour of these representatives of the town’s female underclass.

To be socially and morally acceptable, a Victorian woman’s sexuality and behaviour were expected to be entirely restricted to marriage. She should also be under the authority and care of a man. What troubled Charles were those women who had strayed from this ideal, the most obvious transgressors being prostitutes.

To be socially and morally acceptable, a Victorian woman’s sexuality and behaviour were expected to be entirely restricted to marriage. She should also be under the authority and care of a man. What troubled Charles were those women who had strayed from this ideal, the most obvious transgressors being prostitutes.

If women were naturally passive, streetwalkers must be inherently deviant or the victims of corruption. Here were Torquay’s outcasts, venturing forth from the beer houses and tenements of Pimlico and Swan Street to shamelessly parade the streets in their tawdry clothing. In contrast, men’s sexual desires were seen as an inevitable result of their natures. Effectively, men were not to blame. It was always the doxy and the strumpet.

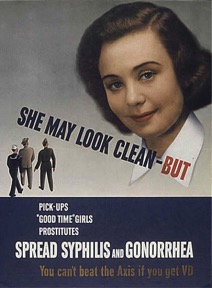

Further causing anxiety was the prevalence of venereal diseases. While the suffering of prostitutes was of little import to the government, the military was found to be the greatest victim of infection. Thus the streetwalker threatened the very Empire itself. In response, Parliament passed The Contagious Diseases Acts of 1864, 1866 and 1869 under which women could be detained and forced to undergo an examination. If a venereal disease was identified, the prostitute would then be forcibly detained in hospital.

Torquay has always had its ‘ladies of the night’. But we also need to recognise the town’s long-established gay sub-culture and the presence of male sex-workers, an even less explored aspect of local working class history.

Torquay has always had its ‘ladies of the night’. But we also need to recognise the town’s long-established gay sub-culture and the presence of male sex-workers, an even less explored aspect of local working class history.

The numbers of prostitutes in Victorian England differ widely depending on who was doing the estimating. In London, for instance, the police claimed there were 7,000, while the Society for the Suppression of Vice said 80,000. A nineteenth century city commonly had 1 prostitute per 36 inhabitants, or 1 per 12 adult males.

While we can’t draw too close a parallel, if we take the above ratios, this would give us over 700 Torquay prostitutes. Even at half this number, sex workers would have made up a significant part of the working class of our town. Hence, we are all quite likely to be able to include a Victorian prostitute amongst our ancestors.

While we have fragmentary evidence from Torquay we do have a great deal of research from other locations, particularly the capital. And Victorian Torquay consciously replicated London, adopting its fashions and terminology, even down to naming its constituent parts after places to be found there, such as Pimlico and Belgravia.

While we have fragmentary evidence from Torquay we do have a great deal of research from other locations, particularly the capital. And Victorian Torquay consciously replicated London, adopting its fashions and terminology, even down to naming its constituent parts after places to be found there, such as Pimlico and Belgravia.

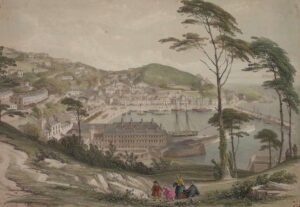

Though prostitution was common throughout the nation, Torquay had its unique characteristics. It was described as the wealthiest town in England, and the affluent needed a large servile class. By 1901 18.5 per cent of the population were employed as domestic servants. A majority of those in service were female, largely due to there being a tax on indoor male servants making men’s wages considerably higher, and that women were regarded as being more obedient. This saw a gender disparity in the town that would persist for over a century. In 1871 there were 12,772 females to 8,885 males in Torquay. In 1881 there was a population of 19,293 females but 13,665 males. By 1911 there were 21,738 females and 17,033 males.

While some women entered prostitution by choice, attracted by its comparatively lucrative remuneration, many were forced or had no other option. For those not able to secure any employment, there were few alternatives. Hence, prostitutes were mainly young, single and aged between 18 and 22. They often worked for short periods in the trade and would settle down in the long run, perhaps marrying former clients.

While some women entered prostitution by choice, attracted by its comparatively lucrative remuneration, many were forced or had no other option. For those not able to secure any employment, there were few alternatives. Hence, prostitutes were mainly young, single and aged between 18 and 22. They often worked for short periods in the trade and would settle down in the long run, perhaps marrying former clients.

Particularly vulnerable were those women who worked as servants in the town’s households and hotels. Many young women had been lured to Torquay with the promise of employment and accommodation. Having left their home villages, they lost the protection of their families and could be seduced or forced into sexual liaisons by fellow workers or employers. Once their ‘virtue’ was no more, any prospect of a future respectable marriage was also lost; and some did support illegitimate children. And it is amongst poorly-paid and bored servile staff that we find the ‘dolly mop’, the amateur, part-time, sex-worker.

It was in this tourist resort setting that we see a reservoir of women, men and children available to satisfy the sexual requests of clients. A high demand was also maintained, not just from local men but from holiday-makers, replaced every week or so and with money to spare. In effect, both supply and demand were constantly being replenished.

As a result there were prostitutes in Torquay suitable for all classes of visitor and for all proclivities: ranging from those who provided very brief encounters in Torre’s alleyways to the ‘grandes horizontales’ who frequented the great hotels.

As a result there were prostitutes in Torquay suitable for all classes of visitor and for all proclivities: ranging from those who provided very brief encounters in Torre’s alleyways to the ‘grandes horizontales’ who frequented the great hotels.

From other towns and cities we read of a robust sex-worker subculture that clearly distinguished prostitutes from other working-class women. As mentioned, dress was one aspect while behaviour, ‘foul language’ and comparative independence from men were further signifiers. Many prostitutes formed strong ties with one another and there are a number of instances of money being collected to pay for a doctor, or to bail a compatriot out of jail. Nevertheless, this was still a world of violence, squalor, alcohol and opium dependency, exploitation and intimidation, with fierce competition over territories.

Furthermore, the inevitable consequence of brief liaisons were left to the not-so-tender attentions of baby farmers; the most notorious local example being Charlotte Winsor who in 1865 was convicted of the murder of Mary Jane Harris’ illegitimate four-month-old son.

The most common form of prostitution was streetwalking and women could be found at night frequenting harbour pubs and Cary Green – the area in front of the Pavilion. This all seems to have been tolerated. However, the authorities took note when things became too obvious.

Unaccompanied women, for example, were often assumed to be prostitutes. In January 1893 the landlord of the Marine Tavern, a one-storey pub situated in front of the Pavilion, was accused of assaulting a policeman and for being drunk and disorderly. However, the defence argued that he was sober and that he had only taken offence when a passing policeman had accused his wife of being “a woman of loose character”.

According to the landlord, he had been waiting at the Fish Quay for the arrival of the ferry which brought in a good deal of his custom. At one point he left his wife alone and a policeman approached her. That’s where reports began to differ. The police said the landlord went berserk and had to be restrained by a number of officers both at the Harbourside and later in the police station. The landlord said that he was assaulted and badly beaten. Despite a number of witnesses saying that the landlord was of good character and had not been drinking, and familiar accusations that Torquay’s police had a tendency towards being heavy handed, the court accepted the testimony of the police and the publican was jailed and lost his living.

According to the landlord, he had been waiting at the Fish Quay for the arrival of the ferry which brought in a good deal of his custom. At one point he left his wife alone and a policeman approached her. That’s where reports began to differ. The police said the landlord went berserk and had to be restrained by a number of officers both at the Harbourside and later in the police station. The landlord said that he was assaulted and badly beaten. Despite a number of witnesses saying that the landlord was of good character and had not been drinking, and familiar accusations that Torquay’s police had a tendency towards being heavy handed, the court accepted the testimony of the police and the publican was jailed and lost his living.

Generally, however, the activities of Torquay’s poor were rarely acknowledged… unless they attracted the attention of the authorities or reached the courts. Only occasionally did a public example have to be made.

In 1899 the landlord of the Abbey Inn on Abbey Road was charged with allowing his pub to be used as “a habitual resort of women of ill-fame”.

A Detective Thomas had watched the Inn on the night of March 12 between the hours of 8 and 11. “He saw women of loose character enter. They stayed for a considerable time – between 10 and 25 minutes. They entered and returned several times on the same evening, sometimes alone and sometimes in company with men… Entering the Inn, he saw three loose women in one of the rooms.”

Women of good character were unlikely to visit an inn alone and so evidence of impropriety included a notice instructing females not to remain in the house for more than a quarter of an hour.

On one occasion the detective heard the landlord shout, “Time, Ladies!” indicating that women were not being escorted by a man. While being cross-examined, Detective Thomas said, “There is nothing to distinguish them from others except their bad language. The house was a quiet one and perhaps was not likely to attract women of the town in pursuit of their vocation.”

The defendant protested on his arrest, “What can I do with so much rates and taxes to pay. They bring me my living.” Disregarding this defence, he was fined £5 with £1 costs and the brewery took away his tenancy.

For well over a century the message remained the same. There were dangerous women on the streets of Torquay.

In early 1914 a ‘Big Meeting of Men’ was held in Torquay Town Hall by the YMCA. 800 young men were there to listen to a series of speakers.

In early 1914 a ‘Big Meeting of Men’ was held in Torquay Town Hall by the YMCA. 800 young men were there to listen to a series of speakers.

“Hundreds of lads went under in the moral life every year either through ignorance or curiosity. Filthy picture postcards often led to a loose and unclean life. In Torquay there were thousands of girls and women decking themselves out in bright clothing and donning tawdry jewellery that they might walk the streets and try to attract so-called men and young men”.

Even as late as the Second World War it was deemed necessary to issue warnings of the hazards lurking on the home front. Such cautioning still apparently warranted a degree of discretion and so obscure references continued to baffle the unworldly. When RAF trainees were billeted at the Grand Hotel in 1940, one remembered attending a lecture at which “an ancient aircraftmen” warned them that, “There are lots of ladies down here from London who hand out bags of sweets”. It was only later that the trainees realised what their lecturer had been alerting them to.

There were always some pioneers, churches and workers’ organisations, that campaigned for change and which offered sympathy, solidarity and support. The future Prime Minister William Gladstone lived in ‘Delmonte’ in Rock Road during 1832 and worked at considerable risk to his political career to try to rescue fallen women from their predicament. Harbourside resident Elizabeth Barrett Browning also depicted prostitutes sympathetically as she explored traditional morality. Another visitor to the resort was Charles Dickens who, in ‘David Copperfield’ (1849) and ‘Oliver Twist’ (1837), humanised sex-workers. With the help of his rich, philanthropic Torquay friend, Lady Burdett-Coutts, Dickens set up and managed London’s Urania Cottage, a home for fallen women.

By the beginning of the twentieth century society had changed. The numbers of live-in servants had declined leaving fewer opportunities for predatory employers. Nevertheless, the trade continued. Even into the 1950s women were still to be found loitering on the Strand waiting to take their customers to the darker recesses of Rock Walk.

It was the introduction of the welfare state that reduced the poverty that caused many to take up the profession. Legislation then came in the form of the 1956 Sexual Offences Act which made brothel-keeping an offence, while new restrictions to reduce street prostitution were added through the 1959 Street Offences Act which stated, “It shall be an offence for a common prostitute to loiter or solicit in a street or public place for the purpose of prostitution.”

Street prostitution declined in the face of the heavy fines imposed on streetwalkers, while the penalty for living off immoral earnings increased to seven years’ imprisonment. Some then became ‘call girls’ where the client makes an appointment. So perhaps it was the mass availability of the telephone, rather those actions by the authorities, which really reduced the most obvious manifestation of sex working.

Of course, the oldest profession continues in Torquay. Now though it is mostly to be found amongst women with alcohol and substance dependence, or those trafficked into town and forced into prostitution. We accordingly applaud the work of the local organisations that are out there offering those vulnerable women support.

‘Torquay: A Social History’ by local author Kevin Dixon is available for £10 from Artizan Gallery, Lucius Street, Torquay, or:

https://www.art-hub.co.uk/product-page/torquay-a-social-history-by-kevin-dixon