On the Churston limestone plateau, in the late Bronze Age/early Iron Age field system on the cliff top at Babbacombe’s Walls Hill, and in earthworks at Warberry Hill, Great Hill and Gallows Gate, there are still traces of the Bay’s original inhabitants. These are the settlements of the first natives of Torbay – who would become known as the Celtic Dumnonii people.

There are also enclosed hilltop sites at Milber Down (pictured above) and Berry Head. These were originally thought to be forts, yet such earthworks are often too large to be defended or in places that were exposed to the elements. Consequently, they are now being seen as places where religious rituals were carried out.

The Dumnonii were one of the tribes who occupied Britain before the arrival of the Romans in the first century (see above). The Romans established a 42-acre fort in around AD 55. The fort was the southwest terminus of the Fosse Way and served as the base of the 5, 000-man Second Augustan Legion which would dominate south Devon for 350 years. The Romans referred to Exeter as Isca Dumnoniorum, ‘Watertown of the Dumnonii’.

Ideally, we should just be referring to Iron Age tribal societies, but Celtic seems to have become a general term to cover the non-Roman inhabitants of the British Isles – and is still often used to identify the peoples beyond the territories occupied by the Anglo-Saxons of northern Europe, such as the Irish, Welsh and Cornish. To be precise, the term Celt really refers to a family of languages and came to cover widely differing tribes across the whole of Europe. We can blame Julius Caesar for saying that the people known to the Romans as Gauls (Galli) called themselves Celts… and the name just came to cover all those who Rome encountered and usually conquered.

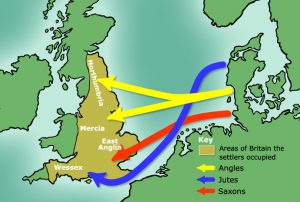

The Romans occupied Britain for around 400 years. Following the end of Roman power in Britain around the year 410, the Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain began as the land gradually became occupied by invaders from northern Europe. From the mid-fifth to early seventh centuries this process of settlement changed the language and culture of most of the south and east of what became England, from Romano-British to Germanic. These Germanic-speakers, themselves of diverse origins, eventually developed a common cultural identity as Anglo-Saxons and established kingdoms in the south and east of Britain, later followed by the rest of modern England.

Yet, it took a long time for Anglo Saxon raids westwards, beginning about 660, to end with a final conquest of Devon by Wessex under King Aethelstan (pictured above). Certainly, the far South West remained ‘Celtic’ for much longer than other parts of England. This could be where we get origins of the legend of King Arthur – the leader of the Romano-British and, possibly, Christian resistance to pagan Anglo-Saxon invaders. Nevertheless the far west did fall. In 927 Aethelstan expelled what he called “that filthy race” of Britons from Exeter. In 936 there was a battle against King Howel of the West Welsh at Haldon Hill above Teignmouth where the West Welsh were finally routed. ‘West Welsh’ in medieval English sources usually refers to the Cornish or Dumnonians, so we could be looking at a confederation of ‘Celts’. It was Aethelstan (924–939) who fixed the boundary between the English and Cornish peoples at the east bank of the River Tamar.

So what happened to the Dumnonii after their defeat? We know that some left Devon and Cornwall altogether (see above). In the 5th and 6th centuries, after the fall of the Roman Empire, it seems that many Britons fled the Saxon invasion and moved to western Armorica in what we now know as France – the area they settled came to be called Lesser or Little Britain, or Brittany which means ‘Britons land’. Later petty kingdoms were known by the names of the French counties that succeeded them. Hence, we have the county of ‘Domnonee’ from Devon’s immigrants.

And while we have evidence of displacement and occupation in place names we also have evidence of survival. Formerly written ‘Peyton’, ‘Payngton’, and ‘Paington’, Paignton is derived from ‘Paega’ which is an Anglo-Saxon personal name, with ‘ton’ a settlement. Paignton, therefore, appears to be a new Anglo-Saxon community – ‘Paega’s settlement’. On the other hand, it is thought that the name ‘Brixham’ comes from Brioc’s farm. ‘Brioc’ was an old English or Brythonic Celtic personal name and ‘ham’ is derived from Old English. So, is Paignton originally Anglo-Saxon and Brixham originally Celtic? Such coexistence is supported by old records that show that the Celtic language was still being spoken in the South Hams in the Middle Ages.

It was originally thought that the Anglo-Saxons had invaded and either killed all the ‘Celts’ or forced them to flee to Cornwall or Brittany. We now believe that the Dumnonii outlasted the Roman period and continued until at least the seventh century. By then they were largely Christians. Evidence of the conversion of the Bay’s scattered settlements may be seen in the name of Preston, ‘preosta tun’ the priest’s farm – possibly a mission station.

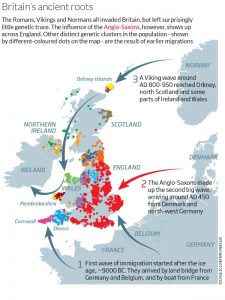

However, in 2015 groundbreaking research found that, remarkably, some Devon folk still retain a Celtic presence in our DNA – 1500 years after the Anglo-Saxon invasion. It looks like the Dumnonii Britons of Torbay survived the invasion. In this UK wide genetic test it was discovered that there are separate genetic groups in Cornwall and Devon to the rest of Southern England, suggesting that the Anglo-Saxon migration into Devon was limited rather than a mass movement of exterminating Saxons.

So the original Britons seem to have gone ‘underground’. And they’re still out there in Brixham, Paignton and Torquay…